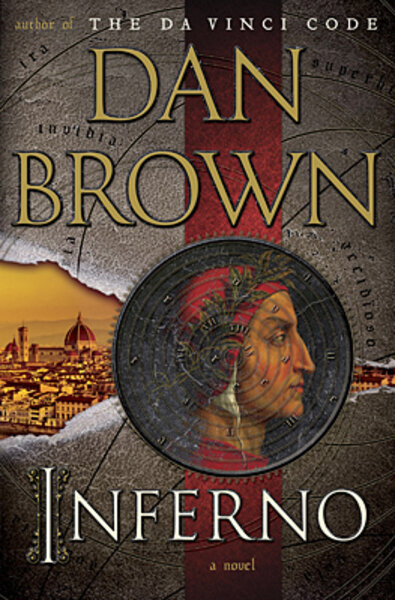

Will Dan Brown's 'Inferno' be heavenly for Dante and Florence?

Loading...

| Rome

It promises to do for Florence and Dante what "The Da Vinci Code" and "Angels and Demons" did for the Vatican and Leonardo.

Dan Brown’s new book, "Inferno," went on sale around the world on Tuesday, with expectations that it will be as wildly popular as his previous blockbusters.

It is based on Dante's "The Divine Comedy," the epic poem that takes the reader on a journey through Heaven, Hell, and Purgatory.

Scholars, however, are divided over whether Brown’s populist thrillers encourage greater interest in history, art, and Renaissance culture, or cheapen the legacies of some of the Western world’s cultural giants. While some welcome the spotlight that Brown shines on the likes of Leonardo or Dante, others argue that he distorts historical reality by postulating conspiracies, codes, and enigmas where they do not exist.

A Florentine puzzle

Dante was born in the Tuscan city in the 13th century and much of "Inferno" is set amid its piazzas and palazzi. The book begins with a character called “the Shade” racing through the streets of Florence while being pursued by nameless enemies.

“Along the banks of the River Arno I scramble, breathless ... turning left onto Via dei Castellani, making my way northward, huddling in the shadows of the Uffizi. And still they pursue me,” Brown writes. “I pass behind the palazzo with its crenellated tower and one-handed clock ... snaking through the early-morning vendors in Piazza San Firenze. Crossing before the Bargello, I cut west toward the spire of the Badia....”

We then find Robert Langdon waking up in a hospital with a serious head wound and memory loss. Initially he assumes he is in Massachusetts General Hospital but is then told that in fact he is in Florence.

Mr. Landon is then swept up in a race against time to prevent a deadly plague-like virus from being spread around the world by an evil genius determined to prevent the planet from being overpopulated.

But instead of battling the evil Illuminati or the Priory of Sion, he is up against another shadowy group of international conspirators – The Consortium. Langdon has to solve mysterious codes that allude to passages from Dante’s poem.

Scholarly debate

Dante scholars might have reason to be sniffy about all this, but in fact the Italian Dante Society has welcomed "Inferno," saying anything that brings “Il Somma Poeta” (the Supreme Poet, as he is known to Italians) to a broader audience is a good thing.

“The book will focus attention on Dante, an extraordinary Florentine who was not just a writer but also a politician. There is great anticipation in Florence for its publication. I’ll certainly buy a copy," says Eugenio Giani, the president of the society.

“The Divine Comedy is 600 years old. It can survive a few mistakes being made by Dan Brown,” says Mr. Giani, who is also head of Florence city council. His office is in the city's Palazzo Vecchio, a magnificent early Renaissance building where Machiavelli once worked and schemed.

Giani is looking forward to meeting Brown – the American author is due to give a talk in Florence next month as part of a literary festival.

But Martin Kemp, the emeritus professor of the History of Art at Trinity College, Oxford, notes that there is a down side to that attention.

Professor Kemp, one of the world’s foremost experts on Leonardo da Vinci, knows more than most what happens when Brown draws from a historical figure for one of his hugely popular novels, as he has been plagued by what he calls “Leonardo loonies” ever since "The Da Vinci Code" was published in 2003.

“It is a privilege to be involved with a historical person who still lives in the imaginations of today, and the fictional portrayals are part of this,” he says. “But with respect to Brown’s claims to historical reality, his impact has been pernicious, since he has sent the ‘Leonardo loonies’ on the hunt for hidden codes of an entirely fanciful kind.”

A boon for Florence?

"Inferno" was featured on the front page of La Nazione, Florence’s main newspaper, on Tuesday, with a review of the book inside.

Florence, like the rest of Italy, has been hard hit by the recession and has seen a decline in the number of tourists coming to the city.

There are high hopes that the book will lead to an increase in visitors to make up for the shortfall of the last couple of years. Just as "The Da Vinci Code" inspired tours of Paris, so tour guides in Florence are expected to waste no time in offering itineraries based on the locations featured in "Inferno."

“My hope for this book is that people are inspired either to discover or rediscover Dante. And, if all goes well, they will simultaneously appreciate some of the incredible art that Dante has inspired for the last 700 years,” Brown told The Associated Press in an interview to coincide with the release of the book.

If sales of his previous books are anything to go by, the number of people who will be introduced to Dante and his works will be enormous – "The Da Vinci Code" alone sold more than 80 million copies and his thrillers have been translated into more than 50 languages.