Slew of new investigations leads to Germany's arrest of alleged Auschwitz guard

Loading...

German authorities have arrested a man who they say was a longtime guard at the Auschwitz extermination camp in Poland, reopening old questions around how the country should deal with its last living participants in the Holocaust.

Hans Lipschis, who is 93, was taken into custody Monday after police announced they had “compelling evidence” that he was complicitous in the mass murder that took place at the camp, the BBC reports.

The arrest is the first to emerge from new investigations by Germany into 50 former Auschwitz guards.

"The arrest of Lipschis is a welcome first step in what we hope will be a large number of successful legal measures taken by the German judicial authorities against death camp personnel and those who served in the Einsatzgruppen [mobile killing units]," said Efraim Zuroff, Israeli head of the Simon Wiesenthal Center, which is known for tracking Nazi war criminals, in a statement to Reuters.

The new cases are propelled by a new legal precedent set during the trial of John Demjanjuk, a Nazi guard convicted in 2011 of serving as an accessory to murder despite the fact that no evidence existed of a particular crime or victim.

In that case, a court ruled that in such cases it was unnecessary to provide a specific list of criminal acts – the generalities of the work were enough to call the defendant guilty.

As the Monitor reported at the time, the case provided a boon for Germans who would like to see a larger number of former Nazis prosecuted for their crimes.

Germany is perhaps unique in that its legal system does not provide a statute of limitation for murder, stemming from a ruling in the 1960s made explicitly to help German prosecutors bring Nazi war criminals to account….

Critics say that while memories are long here, and Germans have done much to own up to their country's past, legally speaking, Germany has not shown the same determination in prosecuting Nazi war criminals.

According to the Simon Wiesenthal Center in Jerusalem, the 90,000 indictments brought against accused Nazi criminals between 1949 and 1985 in Germany brought only 7,000 convictions. "Just because the people were not [Heinrich] Himmler doesn't mean they should not be brought to justice," said Efraim Zuroff, the center's chief Nazi hunter.

Mr. Demjanjuk’s case, however, also opened old questions into the culpability of mid-level guards in the Nazi system, who have frequently argued they were merely following orders during their work at the death camps.

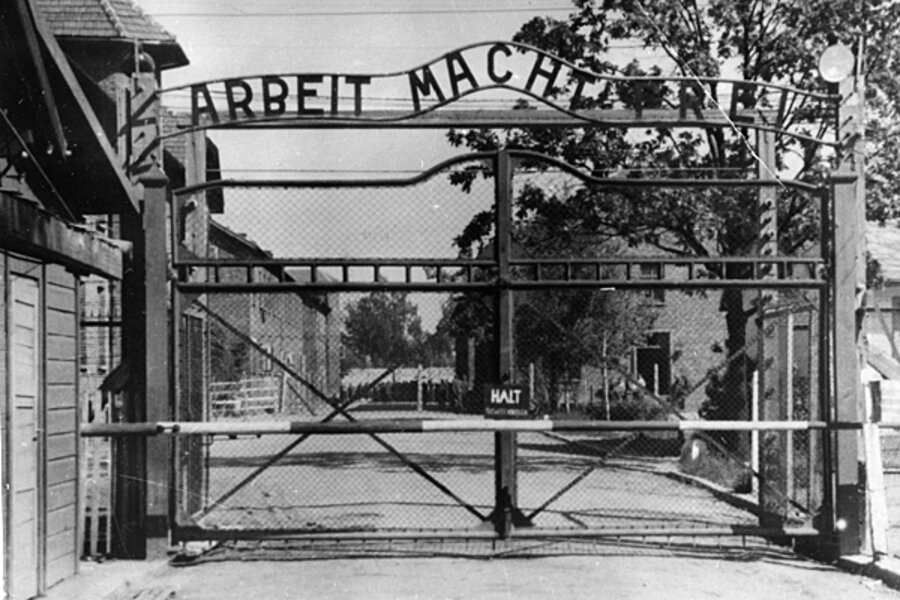

As for Mr. Lipschis, prosecutors say they believe he served as a guard at Auschwitz, the largest and most notorious of the Third Reich’s extermination camps, between 1941 and 1945. Lipschis admits that he worked at the camp, but says he was only a cook.

Lipschis was born in 1919 in what is now Lithuania. In 1956, he moved to Chicago, but was expelled from the United States in 1983 for concealing his Nazi past.

He is currently fourth on the list of “Most Wanted Nazi War Criminals” published by the Simon Weisenthal Center.