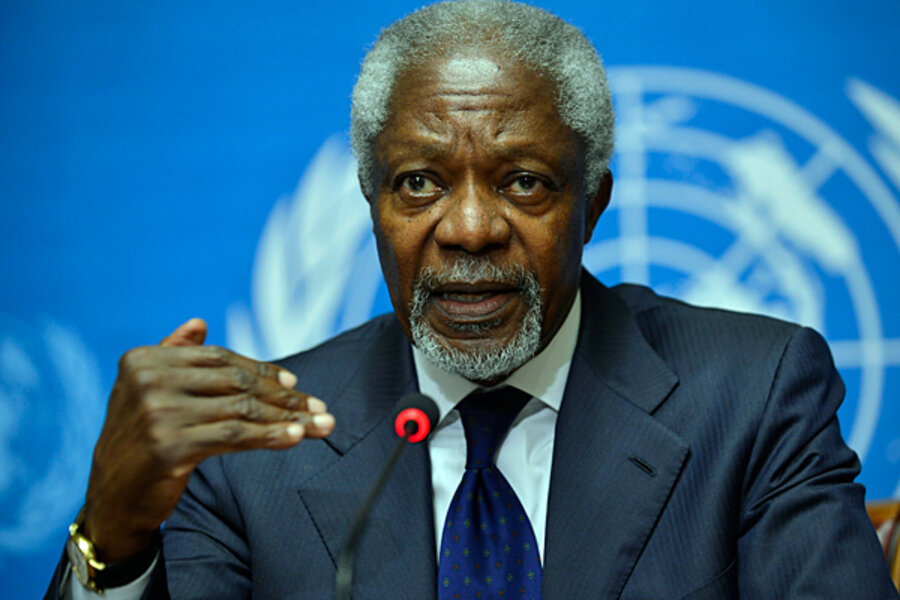

Syria: Kofi Annan steps down

Loading...

| BEIRUT

The resignation of Kofi Annan, the point man for international efforts to bring peace to Syria, emphatically confirmed what events on the ground had already been making clear: The country’s fate is far more likely to be decided by force than by negotiations.

The former U.N. secretary-general’s announcement Thursday that he was ending his attempt to negotiate an end to the conflict came amid a sharp increase in fighting that began after a bomb killed four top security aides to President Bashar Assad last month.

While government forces subsequently pushed insurgent bands out of the capital, Damascus, they are now locked in what could be a decisive battle for the northern city of Aleppo, Syria’s commercial hub and most populous urban center.

“Most people have concluded that this is not going to be settled by talk at the U.N., but by developments on the ground,” said Robert Malley, a former Clinton administration official now with the International Crisis Group think tank.

In comments to reporters Thursday, Annan voiced an opinion he had never before uttered publicly — that, as part of the solution he had been seeking for Syria, Assad would have to go.

“The transition meant President Assad would have to leave sooner or later,” Annan said in Geneva.

He cited the Syrian government’s “intransigence” and the opposition’s “escalating military campaign” as major impediments to his peace efforts, along with a lack of unity in the international community on how to deal with the crisis.

The conflict in Syria, analysts say, has already moved into a new phase that in some ways resembles 1980s Afghanistan, a kind of proxy war for foreign interests in which Western-backed guerrillas are fighting to topple an ally of Moscow.

While the Kremlin does not have troops in Syria, as it did in Afghanistan, Assad received diplomatic cover from Russia, a long-time ally. And Assad also maintains the backing of Iran, a neighbor and regional power.

The Obama administration this week reportedly signed off on clandestine action by the CIA on behalf of the Syrian rebels seeking to overthrow Assad. The White House has also agreed to bolster “non lethal” aid to the opposition and make it easier for outside groups to aid the rebels.

The United States and its allies are providing increasing amounts of aid to a highly decentralized rebel force that has a substantial Islamist element — including some admitted sympathizers with al-Qaida.

Washington has said it is not supplying arms to the rebels. That task appears to have been outsourced to allies Saudi Arabia and Qatar. Those Gulf monarchies, dominated by Sunni Muslims, are intent on helping Syria’s Sunni majority overthrow Assad’s government, which is dominated by the Alawite sect, an offshoot of Shiite Islam.

The departure of Annan, who served since late February as the U.N. and Arab League peace envoy to Syria, would seem to signal the unraveling of his six-point peace plan. Inside Syria, both sides in the conflict have long ignored Annan’s blueprint, which, among other things, called for the withdrawal of troops and armor from populated areas.

Instead, the small contingent of U.N. observers still on the ground in Syria said this week that the government had begun using jet fighters — a significant escalation of previous tactics. Meanwhile, insurgents were deploying tanks and other heavy weaponry seized from the military.

On the ground, the brutality of the conflict is increasingly evident, with almost daily reports of “massacres” by both sides. A widely circulated video uploaded onto YouTube this week documented the execution of alleged pro-government militiamen by rebels.

Annan, a Nobel Peace Prize laureate, voiced deep frustrations with his effort to overcome profound divisions among global powers on how to stop a conflict that has already cost more than 10,000 lives.

“I can’t want peace more than the protagonists, more than the Security Council or the international community for that matter,” Annan said. “Syria can still be saved from the worst calamity — if the international community can show the courage and leadership necessary.”

The spillover effect has already been enormous. Fighting has sent more than 200,000 refugees streaming into neighboring nations, including Lebanon, Jordan, Turkey and Iraq. Cross-border battles have erupted along the Lebanese frontier, while Turkey moved up troops and anti-aircraft batteries to its border after Syria shot down a Turkish warplane.

It remains unclear what exactly the U.N. can do. Major powers such as the United States and its allies are hesitant to intervene militarily in Syria, with its complex ethno-religious makeup and its still-formidable military arsenal.

Russia, with veto powers in the Security Council, was determined to avoid any kind of Libya-style Western intervention. On three occasions, Russia and China blocked Security Council resolutions that could have led to sanctions against the government of Assad, whose family has ruled Syria for more than 40 years.

Susan Rice, the U.S. ambassador to the U.N., praised Annan for taking on a ‘thankless and difficult task.” She blamed the Syrian government, and without naming them, the Russians and the Chinese, for its failure.

Annan’s mission “could never have succeeded so long as the Assad regime continuously broke its pledges to implement the Six Point Plan and persisted in using horrific violence against its own people,” she said, adding that Security Council members who blocked resolutions that would have penalized Assad “effectively made Mr. Annan’s mission impossible.”

Russian officials appeared to be surprised by Annan’s resignation, and one official put the blame on the West. “Annan must have quit because he realized he will not get the backing he needed from the West,” said Leonid Kalashnikov, deputy chief of the Foreign Relations Committee in the Russian State Duma, the lower house of parliament.

Annan assigned blame to all Security Council members, complaining that at a time “when the Syrian people desperately need action, there continues to be finger pointing and name calling in the Security Council.”

(Staff writers Paul Richter in Washington and Sergei L. Loiko in Moscow contributed to this report.)

©2012 Los Angeles Times

Visit the Los Angeles Times at www.latimes.com

Distributed by MCT Information Services