Efficient cookstoves save trees – and chickens – in Kenya

Loading...

| Gichangi, Kenya

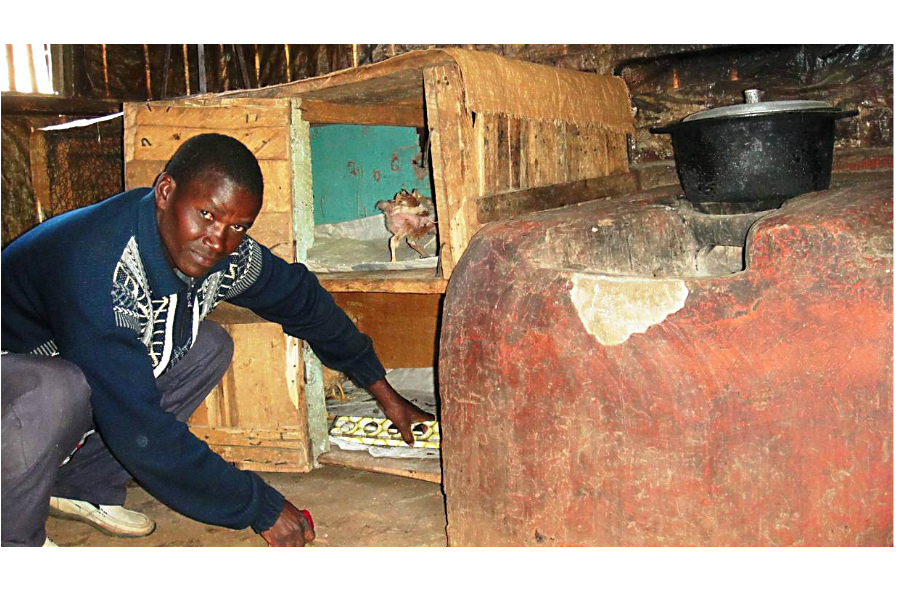

Farmers in Kenya's Laikipia County have found a clever way to reduce their use of wood for fuel while raising more chickens for cash: an efficient ceramic cooking stove that doubles as a chick brooding box.

The locally built stove, used for cooking and home heating in the cool region, contains a separate warming area where chicks can be kept to keep them healthy and safe, farmers say.

The innovation has helped reduce demand for wood in a country hard-hit by deforestation while keeping more chickens alive and raising incomes, farmers say.

"I refer to (the stove) as my support to cutting my expenses and a boost to rearing my chicks," said Duncan Ndegwa, who started using the stove four years ago in Gichangi village, in Nyahururu sub-county. He now earns enough from selling chickens to pay school fees for his three children.

He said the stove, introduced by the Tree is Life Trust, a local non-governmental organization, has helped him cut his use of wood for cooking and heating by two-thirds, saving him about 600 Kenyan shillings ($6) a week in fuel costs.

That has helped cut deforestation in a country where an estimated 93 percent of Kenyans still use fuels such as charcoal, firewood or paraffin for cooking, according to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics and the U.S.-based Society for International Development.

Kenya is currently trying to boost its amount of forest from 6.9 percent of its land area to 10 percent, to protect its water supply and biodiversity, and to limit climate change.

"Using (the stove) improves people's livelihoods while reducing degradation of the environment," said Thomas Gichuru, executive director of the Tree is Life Trust, based in Nyahururu.

The stove won a Green Innovation Award from Kenya's Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources in 2014. The prize recognizes an innovation that contributes to curbing climate change or helping people adapt to it.

The stove was developed by the trust and originally piloted in Ng'arua village in Laikipia West sub-county.

The efficient ceramic stove – about 1,800 of which are in use in Laikipia and Nyandarua counties – has helped Ndegwa boost his chick survival rate from less than 30 percent to nearly 100 percent since he installed it, he said.

"Recently I sold all the 40 chicks I had in the brooder to pay fees for my son, who had just joined high school. None of the (chicks) died," he said.

"I could get three to eight out of 30 hatched chicks (to survive) when I raised them free range because many died from cold-related complications and others were eaten by predators. And the surviving chicks took six months to attain a marketable weight. But I have managed to sell in two months those I have raised with the stove," he said.

Laikipia County lies on the equator but has a cool climate. At times, temperatures drop to just 8 degrees Celsius (46 degrees Fahrenheit), which can kill chicks or slow their growth.

The ceramic stove brooder, four feet (1.2 meters) long and two feet (0.6 meters) wide, can remain warm for 12 hours after being stocked with wood, and holds a maximum of 70 chicks.

With the stove, a farmer can separate chicks from the hen immediately after hatching and keep them in the brooder. That helps the hen start laying eggs again after three or five days, Gichuru said.

Normally farmers let the hen raise the chicks until they are old enough to fend for themselves, which can keep the hen from laying again for several months.

The stoves cost less than 2,000 Kenyan shillings ($20) to install since they are made from locally available materials, Gichuru said.

For farmer Joseph Mwangi, who carries his chickens to market in Laikipia West on a motorcycle, along 23 kilometers (14 miles) of bumpy roads, the stove has turned around his once faltering business since he installed it two years ago.

"I have tried to raise poultry for more than 20 years but often the chicks died from cold," said the farmer from Moroto village. "I almost gave up but I am happy I have been able to successfully raise an average of 50 chicks with this stove."

Each small tree he cuts for firewood now lasts a week rather than three days, he said.

Absalom Ragira, an environmental specialist with the Tree is Life Trust, said use of the ceramic stove supports the government's efforts to expand forests, reduce poverty and promote the well-being of people.

In June, Kenya's Treasury reduced the import tax on energy-saving stoves from 25 percent to 10 percent to encourage their uptake.

• Editing by Laurie Goering. This story originally appeared on the website of the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters that covers humanitarian news, women's rights, trafficking, corruption, and climate change. Visit www.news.trust.org.