Iraq's crisis: Who's involved and what can they do about it?

Loading...

The specter of large-scale sectarian fighting that was put in motion by the Shiite-dominated government in Baghdad within days of the US being kicked out of the country in 2011 is finally upon Iraq.

As Wayne White writes, the surprise is not that Iraq is once again coming apart at the seams, but that it took so long. Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, from the Shiite Islamist Dawa Party, has spent much of the past year purging Sunni Arabs from the government's ranks; pursuing a politically motivated terrorism prosecution of the country's most senior Sunni Arab politician; and breaking up peaceful Sunni Arab protest encampments by force.

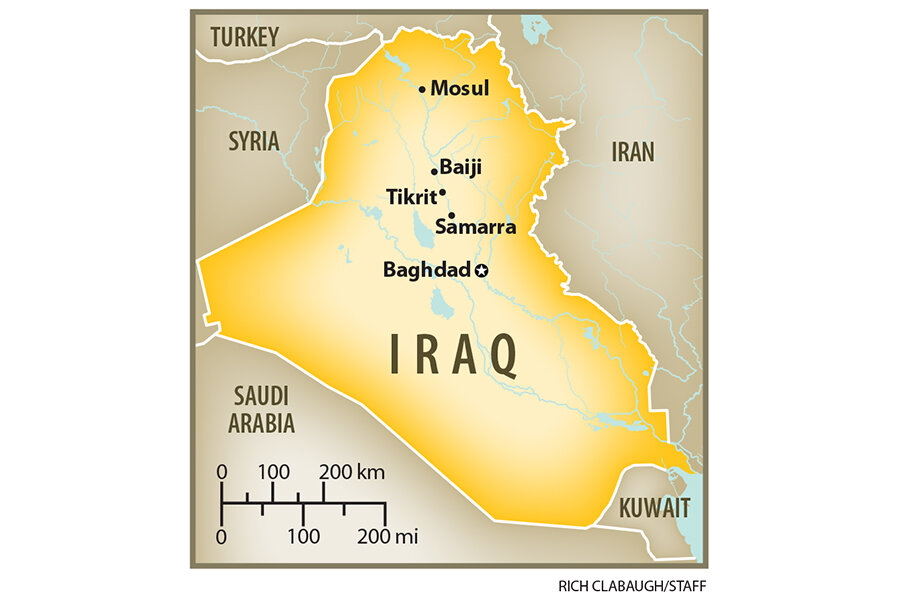

Though the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS), a jihadi group that until recently was focused on fighting in Syria's civil war, has been credited with leading the assault, reports from the ground make it clear that other disaffected Iraqi Sunnis – former Baathists, other Islamist militias – participated in the fight. In Mosul, which fell Tuesday, the Iraqi Army was widely disliked and seen as occupiers from the Shiite south. Sunni insurgents are now pushing south.

ISIS has opened prisons, and residents of Mosul and towns like Tikrit have flocked to the fight against the central government. With the Iraqi military in disarray and Kurdish forces, probably the most capable in Iraq, focused on defending their territory and expanding it to oil-rich Kirkuk, it's anyone's guess how far the uprising will advance.

Starting in 2006, the US convinced Sunni-Arab tribes to fight jihadis in exchange for promises of money and jobs in the government. This Sahwa, or "Awakening," fell apart after the US left: The Maliki government abandoned and harassed them. A recent ISIS propaganda video shows militants forcing a Sahwa commander and his son to dig their own graves. The chances of Maliki convincing the Sunni tribes to stick their necks out for him anytime soon are slim. More likely is that ISIS alienates Iraqi Sunnis who don't share its harsh view of Islam, as its forerunner Al Qaeda in Iraq did in the middle of the last decade.

What are the options and likely responses of the key players, near and far, in the Iraqi crisis?

Iran and Hezbollah

In the 1980s, Iran waged a bloody war with Iraq that left an implacable enemy and rival in the form of Saddam Hussein on its doorstep until he was removed by the US invasion of Iraq in 2003. Now, almost 35 years on, it has a friendly government led by Shiite-Islamists in Baghdad. It has no desire to see a reassertion of Sunni Arab power in Iraq.

Persistent reports from Iraq suggest that members of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard are already in Baghdad advising Iraqi government troops. Iranian President Hassan Rouhani indicated on state television today that his country is ready to get into the thick of the fight.

"This is an extremist, terrorist group that is acting savagely," Rouhani said of ISIS, adding that Iran would not "tolerate this violence and terror" in its neighbor. "For our part, as the government of the Islamic Republic of Iran we will combat violence, extremism and terrorism in the region and the world," he said.

Then there's Lebanese Shiite army Hezbollah, which is backed by Iran and has been fighting on the side of the Syrian government against ISIS and other rebels. Could it move into Iraq and help shore up Maliki? This would be a higher priority for Iran than defending Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. But Hezbollah is tied up in Syria.

Moreover, ISIS and its allies have captured an array of US-supplied weapons from Iraqi forces, including tanks, armored personnel carriers, and artillery. Pictures have started to circulate of some of these weapons being moved into Syria, where ISIS has been battling other rebel groups for control of the oil-rich province of Deir Ezzor. If they can win there, and consolidate their position in Iraq's Niniveh Province (of which Mosul is the capital), their ability to threaten Assad will grow.

The US

The United States spent roughly $2 trillion on the war in Iraq, and trained and equipped what US politicians and officers repeatedly said was a capable and professional army. That claim has been shown in recent days to have been, at best, overly optimistic. The US accelerated the delivery of helicopters and missiles to Baghdad earlier this year, but that aid has done little good.

In 2011, Maliki was glad to see the back of the US, as were his allies in Tehran. Now he seems to be turning to the US as a potential savior. The New York Times reports that Maliki asked the US to conduct airstrikes on insurgents last month but was rebuffed. Why? The Obama administration worried that any military support would be useless without a change in political course from Maliki, whose actions have consistently goaded the country's Sunni Arab minority closer to insurrection.

Could the US help now? It's certainly within American military abilities. But holding territory requires boots on the ground, and nobody is talking about US ground forces going in. Iraq's military does not seem sufficiently organized for a counter-offensive at this point, with battles raging in Baiji, an oil-refining town north of Baghdad, and on the outskirts of the Shiite shrine city of Samarra. For now, Iraq's security forces seem intent on holding what they still have, not retaking what they lost.

The Kurds

Kurdish forces are now in control of the oil-rich city of Kirkuk, which they'd like to annex into their autonomous territory, and are also providing aid and shelter to refugees fleeing Mosul, a short distance from the area of Kurdish control. Kurdish leaders has been locked into a dispute with Baghdad for years over control of oil revenues in northern Iraq, and will likely demand concessions from Maliki in return for helping him to regain Mosul.

Those are concessions that Maliki is unlikely to make at the moment, with the next government still to be formed. And the Kurds, in the process of getting what they want, may be happy to see Baghdad weakened.

The Iraqi government and allies

Maliki has called for arming of civilians to fight ISIS – which probably means Shiite militias. The Iraqi parliament failed to reach a quorum for a planned vote on a state of emergency that would give Maliki almost unchecked power. Given that the government has routinely jailed and tortured political opponents with the powers it already has, alarm bells should be ringing. More power for Maliki could well mean more such abuses, and more fuel for the Sunni Arab uprising.

Other Shiite politicians and militia leaders appear to be in the process of mobilizing followers. In Baghdad's sprawling Shiite Sadr City neighborhood, named after Muqtada al-Sadr's father, residents have been stockpiling weapons and getting organized. Sadr, a fiery cleric whose Mahdi Army repeatedly confronted the US and engaged in attrocities against Sunni Arab insurgents and civilians during the occupation of Iraq, called yesterday for the creation of what he called "peace units" to defend Muslim and Christian shrines in the country.

The fear is that should Shiite militias, either aligned with Sadr or other groups, enter the fighting, they would engage in the kind of sectarian reprisal killings that drove Iraq's conflict in 2006 and 2007, when tens of thousands were killed. But with each ISIS success, this scenario looks more likely.

Iraq's government is also at the moment technically a lame duck. A bloc of Shiite parties behind Maliki won the most seats in parliamentary elections last April, but coalition building is needed before a government can be formed. When results were announced last month, Maliki seemed a shoo-in to retain the top spot.

But now, all bets are off in Iraq.