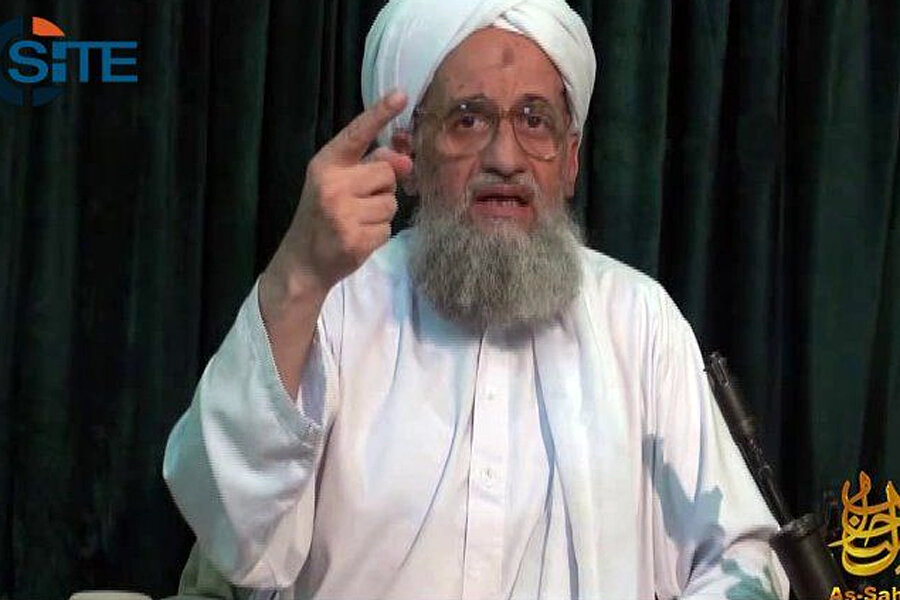

Zawahiri's Al Qaeda in India declaration. Dangerous or desperate?

Loading...

Ayman al-Zawahiri, the leader of Al Qaeda, has had a rough few years. His old boss and friend Osama bin Laden was killed by US forces in a May 2011 raid in Pakistan. Zawahiri, who is also presumed to be in Pakistan, hoped that the Arab uprisings that started that spring would somehow bring him and the group he now leads back to relevance in the heart of the Islamic world.

But while ideologically similar jihad groups have fed on the chaos of the past few years, particularly amid Syria's horrific civil war, the upheaval hasn't exactly benefited Zawahari's dwindling force in core Al Qaeda. The self-declared Islamic State (ISIS) has clearly challenged Al Qaeda in seeking to take up the mantle of leadership of what these men imagine is a global jihad. This summer, ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi declared himself the caliph of the world's Muslims. He has an army, territorial reach, and financial resources behind him that Al Qaeda, even in its heyday, could not have imagined.

Yesterday, Zawahiri struck back. Sort of. In his first audiotape for a year, the Al Qaeda leader declared a new affiliate, "Al Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent." That group's leader, identified as Essam Omar, says on the tape that the "apostates of India" – he identifies them as Jews and Hindus – will be destroyed and promised that jihadis will "storm your barricades with cars packed with gunpowder."

Fighting words. But would this Indian group be able to out-savage ISIS? Hard to see how. And India has more than comfortably weathered the occasional spectacular terrorist attack in the past. But Zawahiri's effort to assert more relevance speaks to how other jihadi groups beyond his control are taking up the mantle. These include the Nigerian militants of Boko Haram, Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, a Yemen-based group, and Jabhat al-Nusra, the Syrian Al Qaeda affiliate that has often done battle with ISIS.

Even in the case of a group like Nusra, Zawahiri's influence has been slipping. Terrorism researcher JM Berger wrote in Foreign Policy on Tuesday about Al Qaeda's apparent growing difficulties in handling its affiliates.

Just a couple of weeks ago, Abu Mariya al-Qahtani, one of the most prominent leaders of al-Nusra Front, posted an extraordinary open letter saying that the Syrian al Qaeda affiliate had repeatedly tried to contact Zawahiri since the caliphate announcement but had received no response. In addition, the letter noted reproachfully, Zawahiri had made no public statement condemning the Islamic State's declaration.

The letter has been underreported, in part because about every other week, a new spate of rumors crops up online that Qahtani is on the outs with al-Nusra's top leader, Abu Mohammed al-Jawlani. While these rumors may or may not be true, Qahtani nevertheless remains one of Nusra's most prominent clerics, seemingly always living on to be fired another day.

Whether or not Qahtani has been cut out of the loop as far as private communications (and there is no particular reason to think he has been), Zawahiri's public silence so far has done little to offset the growing perception that the core al Qaeda has been weakened and put off balance by the Islamic State's dramatic military advances and its audacious religious demands.

It's highly likely that Zawahiri is fully aware of his perceived weakness. This could have prompted the latest tape. Whether it will do him or his movement much good is another question.

The idea of a centrally-controlled global network of salafi jihadists has always been a stretch, and even more so today. Yet 13 years after 9/11 much of the mainstream media and analysis in America seem to lack a firm grasp of what Al Qaeda is, who its affiliates are, and how jihadi groups grow. Consider CNN's treehouse of terror from the other day.

AAUGH!! RT @_RichardHall You know things are bad when CNN whips out the Tree of Terror. pic.twitter.com/S2eVbvL2AM

— Daniel W. Drezner (@dandrezner) September 3, 2014

A nice, linear presentation. The genealogy of jihad starts with Al Qaeda, and various iterations all lead back to that early root. Unfortunately, it's not true. It elides the chaos and egos and competing agendas of the welter of Sunni Arab groups that fight to impose their version of Islam. Have these various groups had links or affiliations with Al Qaeda in the past? Yes. But the vast majority of them have operated almost completely independently, based on their own local cultures and conditions.

Free agents and sectarianism

During the US-led occupation, Al Qaeda in Iraq (later the Islamic State in Iraq) thrived under the direction of the Jordanian Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. While it was meant to be under central Al Qaeda's control, the group was frustratingly independent from the central movement. In 2005, Zawahiri tried to take Zarqawi to task, warning him that his penchant for cutting the heads off of helpless captives and sectarian killings of fellow Muslims was undermining their presumably shared goals. Zarqawi ignored these complaints. Within a year, he was dead in a US airstrike.

By 2006, the US had started to successfully encourage Sunni Arab tribal figures in Iraq to take the fight to that earlier version of the "Islamic State," which they did with gusto. The surviving Syrian and Iraqi members of the group scattered and went underground, reemerging as ISIS thanks to the Syrian civil war and the hyper-sectarian policies pursued by Baghdad's Shiite politicians. The current iteration of this regional movement is as contemptuous of Zawahiri's edicts as Zarqawi's band of thugs was before it.

How about the Taliban, which was seen as hand-in-glove with Al Qaeda? The Taliban are an indigenous Afghan jihadi movement whose roots are deeper, and far different, than Al Qaeda's. Indeed, the last guy to try the old "I'm the Caliph, all the world's Muslims get into line" gambit before Baghdadi was the Taliban's Mullah Omar in 1996. Bin Laden and Zawahari promptly swore allegiance to Mullah Omar as leader of the faith, largely as a practical consideration, since the group depended on his hospitality in Afghanistan.

Follow the leader

That allegiance paid dividends for them. Omar's refusal to hand the men over after 9/11 led to the US-led Afghan war that is now in its second decade. In his latest audiotape Zawahiri was at pains to reiterate his view that Omar, not Baghdadi, is still the leader of all Muslims.

Can Zawahiri turn the tide against the upstart jihadis? For now, it seems unlikely. The small percentage of Muslims that support such movements seem elated by Baghdadi's caliphate declaration, and imagine they're living in epoch-defining times that will see their dream of converting the whole world at the point of a sword realized. The old Al Qaeda approach – that world domination wasn't possible until "far enemies" like the US were somehow destroyed – is being upended by the arguably more conventional ISIS approach of seizing territory.

For the small group of misfits and loners and true-believers who view the chopping of heads and gunning down captives in their hundreds as heroic, rather than revolting, ISIS is the emerging brand name. When was the last time Joe Biden vowed to chase Al Qaeda to the gates of hell?