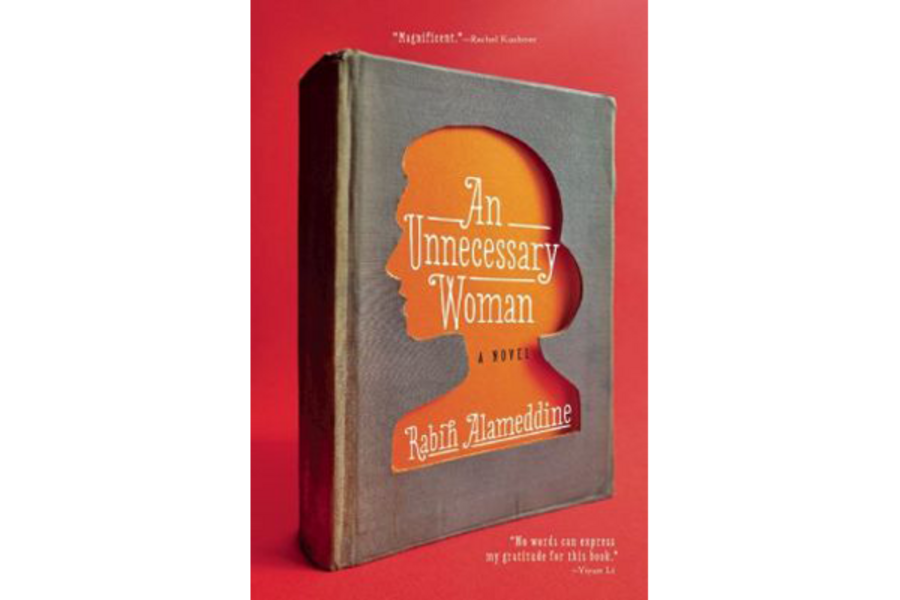

An Unnecessary Woman

Loading...

Call Aaliya Sobhi the Belle of Beirut.

Like Emily Dickinson, Aaliya spends her days alone, writing, in Rabih Alameddine’s contemplative, elegantly constructed new novel, An Unnecessary Woman. Instead of poetry, she translates one book a year, from “Anna Karenina” to “Austerlitz,” into Arabic.

She doesn’t publish them and no one besides her has ever read one of her translations.“Books into boxes – boxes of paper, loose translated sheets. That’s my life,” she says.

When we meet her, it is New Year’s Day. The reclusive 72-year-old woman has, thanks to a misadventure with shampoo, inadvertently dyed her hair blue and is contemplating tackling Roberto Bolanos’s unfinished 900-page novel “2666.”

She worked in the same bookstore for 50 years before it closed and has spent less than 10 days outside of Lebanon’s capital, preferring to remain in the apartment she shared with her husband before their divorce when she was 20. (“Nothing in our marriage became him like leaving it,” Aaliya says with a Shakespearean dismissal of the man her family chose for her at 16.) She only had one true friend in her life, Hannah, whom she lost years before. And, like “Mrs. Dalloway,” the entire book takes place over the course of one day.

But it would be deceptive to say nothing happens in “An Unnecessary Woman.” Alameddine fits an entire, richly lived life into that day – finding room for war, tragedy, AK-47s, and lots of literature. “My books show me what it’s like to live in a reliable country where you flick on a switch and a bulb is guaranteed to shine and remain on, where you know that cars will stop at red lights and those traffic lights will not cease working a couple of times a day,” she says. “When trains run on time (when trains run, period), when a dial tone sounds as soon as you pick up a receiver, does life become too predictable? With this essential reliability, are Germans bored? Does that explain ‘The Magic Mountain?’”

Aaliya is a formidable character. Not only did she hold off her half-brothers and mother for years, who felt she should have handed over her apartment to them and been grateful for a spare room somewhere, she once chased off three men in her nightgown and slept with a Kalashnikov by her bed during the Siege of Beirut in 1982. How she acquired the assault rifle is a tale in itself.

"Beirut is the Elizabeth Taylor of cities: insane, beautiful, tacky, falling apart, aging, and forever drama laden," Aaliya says as she walks through her city, "She'll also marry any infatuated suitor who promises to make her life more comfortable, no matter how inappropriate he is."

Aaliya’s taste for literature runs to the intellectual, from 19th-century Russian and French classics to the literary metafictional – from Tolstoy and Proust to J.M. Coetzee. “Most of the books published these days consist of a series of whines followed by an epiphany,” Aaliya says.

Aaliya wouldn’t stoop to whining, but she might just be due for an epiphany. When “An Unnecessary Woman” offers her what she regards as the corniest of conceits – a redemption arc – it’s a delight to see her take it.

Yvonne Zipp is the Monitor's fiction critic.