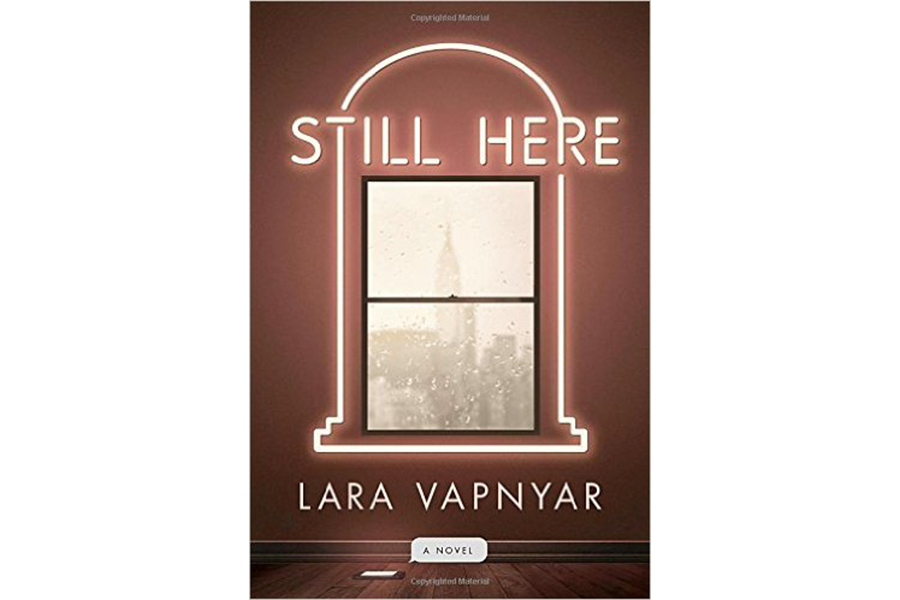

'Still Here' follows Russian immigrants struggling to establish identity in NY

Loading...

Sergey, Vica, Vadik, and Regina – the protagonists of Lara Vapnyar's latest novel Still Here – are all Russian immigrants, attempting to carve out lives for themselves in present-day New York. As they approach middle age, the group of friends take sobering account of what has become of their lives and dreams of success since immigrating to the Big Apple.

Sergey, husband of Vica and an academic struggling to find success as a businessman, has been fired or laid off from every job he has held. Though his naiveté and cheery hopefulness can be irritating to his friends, Sergey is the glue that holds the four together. While living off of severance packages and his wife’s salary as an ultrasound technician, Sergey holds on to the memory of his recently deceased father through the last letter his father sent him. Noting that though his father had passed, his voice lived on through the written word. “His father was gone, dead, yet his voice remained alive and unchanged: dry, skeptical, vaguely ironic.”

Vica, Sergey’s wife, is beginning to resent his continual trial-and-error with jobs which keeps her from continuing her schooling and living a more luxurious lifestyle.

Sergey and Vica’s closest friends, Regina and Vadik, have achieved monetary success, Regina by marrying a wealthy American software developer and Vadik by creating apps for that software developer. But although Regina and Vadik have achieved the lifestyle for which Sergey and Vica strive, they too are discontent with life.

The novel is infused with a stark honesty about the realities of life in a foreign country. As Sergey scrolls through Facebook, he notes that, “In fourteen years in this country, he hadn’t made a single American friend.” Though the four friends get upset with each other at times, none of them venture beyond the friendship of their fellow Russians, feeling that they are not understood outside of this close circle of shared history.

Vapnyar, who immigrated to New York from Russia in 1994, writes from her own experiences. Vapnyar started publishing short stories in 2002 and has written three novels, including “The Scent of Pine” and “Memoirs of a Muse.” Her stories often focus on Russian immigrants, staying true to her own experiences.

The novel is instilled with a sense of melancholy as each of the four friends recognizes their discontent with life. Though they all have access to technology where there is seemingly an app for everything and endless sources of entertainment, each is left unfulfilled.

Vica is resentful that what was a bright and hopeful future when she and Sergey married has been painted gray by the drudgery of working a 9-to-5 job and making ends meet. She pines for more money and success while also realizing that a higher education and a better salary don’t guarantee happiness. While attempting to enroll her son in private school, Vica reflects, “A school like that opened the whole world for you. If you were bound to be miserable, you could have a whole variety of options, you could choose your own misery, not have one forced upon you.”

Vadik flits from lover to lover and apartment to apartment, trying to find a connection with a person and a location that fits with his own perception of his identity. His frequent dalliances through connections on the matchmaking app Hello, Love! leave him unfulfilled, searching for a connection that resonates with his sense of his true identity.

Regina mourns her mother and suppresses her talent as a translator by watching TV and ordering food from an app called Eat'n'Watch.

Sergey grapples with the loss of his father by pitching an app called Virtual Grave that would maintain one’s online presence after one had passed. In pursuing Virtual Grave, Sergey confronts the differences between Russian and American views on death, as well as the degree to which technology is integrated with our lives today. Inspired by the eternal voice of his father’s letter, Sergey says, “Your e-mail. Your Twitter. Your Facebook. Your Instagram or whatever. That’s where people now share their innermost feelings and thoughts, whatever they find funny or memorable or simply worthy nowadays. Our online presence is where the essence of a person is nowadays.” The story raises intriguing questions about life and death in the age of technology.

Vapnyar’s story is infused with a somber tone. Although it is a story about immigrants, the novel also poses a more universal question: How does anyone establish identity and contentedness (in an adopted country or otherwise) once a bright future has lost its shine?