Four-day workweek: Why idea of shorter hours gains support

Loading...

In 1930, British economist John Maynard Keynes predicted that, a century hence, rising productivity would shrink the average workweek to just 15 hours. Needless to say, his prediction was a bit off.

But maybe Keynes’ ideas weren’t as far-fetched as they sound. A growing number of businesses are experimenting with a four-day, 32-hour workweek, with mixed success. Microsoft’s Japan subsidiary tried it in the summer of 2019, and reported a 40% boost in worker productivity. But when the Portland, Oregon, tech education company Treehouse tried it in 2015, the CEO remarked that the reduced working hours killed his “work ethic.”

Since then AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka proposed a “leisure dividend” to compensate workers for their increased productivity. The 2019 manifesto of Britain’s Labour Party advances a similar proposal.

Would a four-day, 32-hour workweek actually work? Many business owners, concerned with foreign competition, remain skeptical. But many workers’ advocates and environmentalists say it would be a change for the better. Even some historians, like Dutch author Rutger Bregman, say that the three-day weekend is an idea whose time has come.

Why We Wrote This

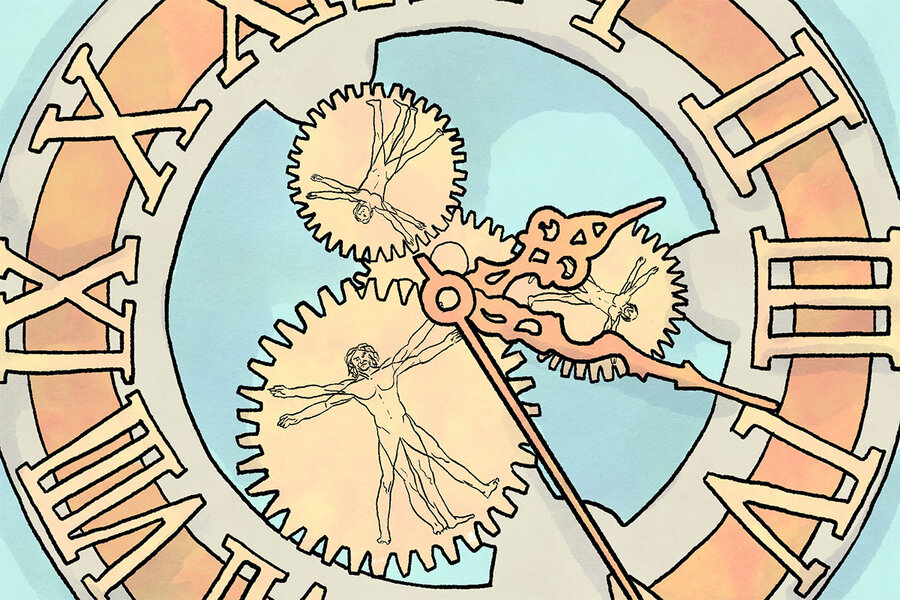

For many people a “full-time job” provides much needed income, even a sense of purpose. But could those needs be supplied without such long work hours? It’s a long-standing question that we revisit in illustrated form.