Summer of labor: Why unions win pay hikes and new clout

Loading...

Every once in a while, events conspire to upend Americans’ views on the economy.

It happened in the 1970s, when postwar confidence in the United States’ industrial might was shattered. Energy shortages, soaring inflation, and relentless foreign competition smashed the view of the American workforce as superior and powerful. Now, such thinking may be shifting in the opposite direction.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onSome old narratives about labor unions and blue-collar decline no longer seem to apply. It’s not clear how far the worker comeback will go, but employees are making their voices heard – and winning pay raises.

A labor shortage of historic proportions, coupled with longer-term trends, has allowed workers to win big pay raises this year. Even nonunion workers are making gains, so that those at the bottom of the pay scale are actually reversing some of the income inequality that has yawned since the 1980s.

“With the tight labor market, we’ve seen this extraordinary phenomena where ordinary workers have been able to get good wage increases,” says economist Dean Baker. But “they have a long way to go. I mean, we’ll have to make up 40 years of losses.”

The question is how persistent the trend may be. Workers are seeking to unionize workplaces even in the South, long known as resistant to organized labor. And UPS workers won a big pay hike recently – including for entry-level workers.

“We are an example of what happens when you are a union, what we can make happen,” says Viviana Gonzales, a UPS worker in Palmdale, California.

Every once in a while, events conspire to upend Americans’ views on the economy.

It happened in the 1970s, when postwar confidence in the United States’ industrial might was shattered. Energy shortages, soaring inflation, and relentless foreign competition smashed the view of the American workforce as superior and powerful. Now, though, such thinking may be shifting in the opposite direction.

A labor shortage of historic proportions, coupled with longer term trends, has allowed workers to win big pay raises this year. From pilots to delivery drivers, union members are getting better contracts. Even nonunion workers are making gains, so that those at the bottom of the pay scale are actually reversing some of the income inequality that has yawned since the 1980s.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onSome old narratives about labor unions and blue-collar decline no longer seem to apply. It’s not clear how far the worker comeback will go, but employees are making their voices heard – and winning pay raises.

“With the tight labor market, we’ve seen this extraordinary phenomena where ordinary workers have been able to get good wage increases,” says Dean Baker, economist and co-founder of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, a research and public education nonprofit based in Washington. But “they have a long way to go. I mean, we’ll have to make up 40 years of losses.”

The question is whether this era is a rare blip in the economy or an inflection point where low-paid workers begin to make gains relative to higher-paid workers. The economics suggest it’s a blip, which will disappear once unemployment rises and jobs become scarce again. But some labor experts point to longer-term trends that could lead to a historic re-balancing of the labor market between the rich and poor.

The enthusiasm and hopes among union workers are palpable.

“I can’t believe the raises and benefits,” says Kenny Riley, president of the Charleston, South Carolina, local of the International Longshoremen’s Association. He’s referring to the 32% pay raise and bonus that his union’s West Coast counterpart, the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, reportedly negotiated in June with shippers and terminal operators in a tentative six-year contract. (The union hasn’t released details.) Mr. Riley is hoping his union, now in talks with East Coast shippers and operators, can match that increase. “The money is there in the logistical chain, and it’s our time to reap the benefits.”

Nonunion workers are also pushing for change.

One day in July, Marshawna “Shae” Parker took a deep breath, put down the coffeepot in her hand, and walked off her job at a Columbia, South Carolina, Waffle House with a raised fist. “I felt lighter than a feather,” recalls the waitress and 23-year veteran of the restaurant chain. “Walking out ... was a weight lifted.”

Outside, she was cheered by a phalanx of workers at a union so new, it’s not yet officially recognized. They are pushing for better pay, a working air conditioning unit, an end to automatic deduction of shift meals, and more security guards to keep staff safe. But she was a lonely striker. No one else at the restaurant walked off that day. Four fellow strikers weren’t at work at the time of the rally. Three days later, after receiving promises that things would change, Ms. Parker went back to work.

Rather than joining existing unions, workers at some of America’s best-known companies have formed their own. Apple, Amazon, Google, and Starbucks employees have all created their own organizations. Sometimes, the members are highly paid workers eager to have their voices heard by management (Google professionals). More often, it’s low-paid employees pushing for better pay and work conditions (Apple store employees, Starbucks baristas, and workers like Ms. Parker at the Union of Southern Service Workers, formed just last year with ambitions far beyond Waffle House). It’s these organizing drives that unions hope will reverse or at least stop their decadeslong decline.

One of the toughest nuts to crack is the South, where states have right-to-work laws.

That means workers don’t have to join unions or pay union dues, even if a union has organized the workplace. Still, organizing is going on at tire plants in the Carolinas and at Amazon facilities in Georgia, including a protest in East Point, Georgia, on July 26. It came just a day after UPS and the International Brotherhood of Teamsters came to terms on a tentative contract, which workers still must approve.

The Teamsters offered an app where UPS drivers could share concerns up the chain to union bargainers – and the issues went beyond pay to what worker Viviana Gonzales calls “issues of dignity.” One high priority: getting air conditioning in vans, including in Palmdale, California, where Ms. Gonzales often sees temperatures climb into triple digits.

Ms. Gonzales, a nine-year UPS veteran and a union shop steward, was on the front lines of preparing workers for a possible strike this month – and the self-sacrifices involved in solidarity.

Now the walkout won’t be necessary.

“We are an example of what happens when you are a union, what we can make happen,” Ms. Gonzales says.

The UPS contract is eye-opening because, even though the union hasn’t officially released the terms, details that have leaked out suggest it is heavily weighted toward helping the lowest-paid drivers, the part-timers.

The tentative contract reportedly gives all workers an immediate pay boost of $2.75 an hour, hikes the minimum starting pay for part-time drivers by 30%, and moves thousands of shift workers into full-time employment. In March, Delta Air Lines pilots approved a contract locking in a 34% raise – a move that has since been matched by other major airlines.

Besides seeking better pay and job protections, union autoworkers are also negotiating to eliminate tiered wages, which allows companies to pay newer workers less than what longtime workers earn. Their contracts with major automakers expire next month.

Obviously, pilots and autoworkers don’t inhabit the bottom of the pay scale. Yet historically, their gains have spilled over into the pay scales of nonunion companies. The contract wins and the organizing pushes, along with other trends, suggest the possibility that a sea change is at hand for lower-paid workers.

Ever since the 1980s, globalization, automation, and anti-union administrations have put blue-collar workers on the defensive. Corporations moved factories abroad or automated them. After the Reagan administration took on striking air traffic controllers – and won – employers have taken a tougher stance against unions. The results were predictable.

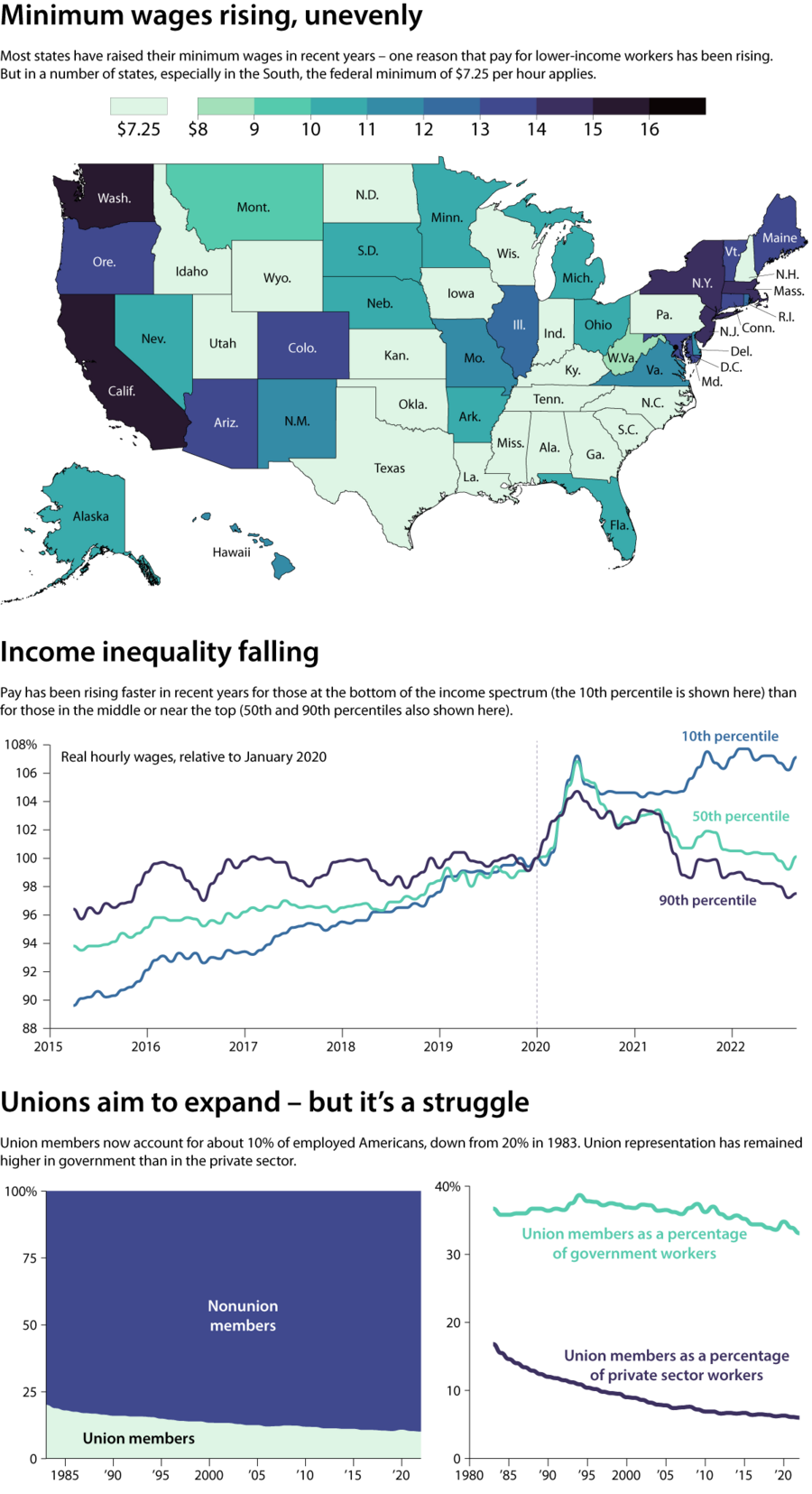

Factories closed. Jobs moved overseas. Unions dwindled in their reach and power. In 1983, 1 in 6 private sector workers belonged to a union; as of last year, the ratio was only 1 in 16. And the rich-poor income gap, which some economists attribute largely to unions’ decline, grew to levels not seen since before World War II.

Now, however, some of those trends are reversing. And the economic assumptions of the past 40 years no longer appear to apply. For example:

Assumption No. 1: Globalization is decimating the blue-collar workforce.

That’s no longer true in strategic industries such as semiconductors and green power. Worried about U.S. dependence on China, the government is subsidizing companies to bring chip production back to America. A decade ago, conservatives and trade activists would have decried such a move as protectionism. Now, the move has bipartisan support because of the growing strategic competition with China. Corporations, also anxious to diversify away from China after the pandemic disrupted their supply chains, are opening factories in other countries or bringing them back home.

The Biden White House, perhaps the most labor-friendly administration since Franklin Roosevelt’s, has pushed through legislation that is also giving alternative energy a huge boost – promising still more blue-collar jobs.

Assumption No. 2: Technology has made white-collar workers, especially so-called creatives, the winners in this economy.

While automation displaced factory workers for decades, its latest incarnation in the form of artificial intelligence now generally poses a greater concern for white-collar workers than blue-collar ones. Even if AI begins to steal jobs away, employees involved in physical labor and consumer-facing service work appear to be somewhat insulated.

This year’s bargaining sessions tell the story. The mere threat of a strike won longshoremen, UPS drivers, and other blue-collar workers big pay raises. The 11,000 members of the Writers Guild of America, by contrast, have been on strike since May. Last month, the actors union joined them on the picket line. It’s the first time the two have jointly struck the studios since 1960 and the most closely watched labor action of the year. Almost 3 in 4 Americans say they’re aware of the strike, according to a Los Angeles Times poll released Aug. 3. Among the issues are revenues from web streaming and the use of AI to generate actors’ likenesses.

“This won’t be a career anymore,” says Adam Conover, a member of the Writers Guild’s negotiating committee, walking the picket line in front of Netflix studios in Los Angeles last month. “If we don’t win this now, we won’t have careers to go back to in five years because they’ll have eliminated the writers room, they’ll have scanned everybody into AI and be stealing their likenesses instead of [using] real actors. ... They’ll put comedy-variety writers like me on a day rate. We’ll go from a 13-week guarantee to a day rate.”

Assumption No. 3: The rich are getting richer while the poor fall behind.

Actually, at least since the Great Recession, workers at the bottom end of the income ladder have seen their pay rise by percentages that outpace those in the middle or even those at the top, according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Much of this reversal in the 2010s can be explained by state actions to raise minimum wages, according to Arindrajit Dube, an economist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and co-author of a study on income trends released in March. Since 2014, 30 states have effectively raised their minimum-wage law, says the Economic Policy Institute.

Then the pandemic hit, which created a worker shortage, especially in low-paid service industries. Wage gains at the bottom accelerated. And they’ve accelerated for all such workers this time, not just those in states with a higher minimum wage. Even after accounting for inflation, low-paid workers have come out ahead in the past three years, while those in the middle and the top have lost ground.

Such gains in the past three years reversed approximately a quarter of the post-1980 widening of income inequality, according to the study.

The pandemic not only caused a worker shortage but also changed perspectives.

“What everyone always thought of as the great mass of ‘low-skilled,’ low-wage service [workers], those folks discovered during the pandemic that they’re essential workers,” says Susan Schurman, professor of labor studies at Rutgers University in New Jersey. “There is a growing demand among workers for a much stronger voice on the job and for American workers. … Really unions are the vehicles through which the average worker or group of workers can get any leverage on the job. There is not another way to do that.”

Whether all these trends amount to a revival of unions’ fortunes remains an open question. Past organizing wins and gains at the bargaining table haven’t triggered a rebound for organized labor. And today’s worker shortage – the longest string of sub-4% joblessness since the late 1960s – may not last. Yes, some demographers warn that declining birthrates could mean a future with fewer workers. But with AI, labor-saving automation could accelerate. And in the near term, as the Federal Reserve raises interest rates and slows the economy to fight inflation, the number of job openings has begun to fall. In July, the U.S. notched the slowest job growth since December 2020.

The contract wins “are definitely real gains,” Ruth Milkman, a sociologist and head of the labor studies department at the City University of New York, writes in an email. But “they may reflect the tight labor market ... as much as anything else.” In the case of UPS, they also reflect the threat of losing market share in a strike, she adds.

Historically, union workers have proved to be the one labor group that can, at times, push against chill economic winds. But labor economists aren’t at all sure that they can do it now when their leverage is limited to a few highly organized sectors of the economy.

Unions are busy organizing other sectors. Last year, the number of petitions for a union at workplaces and the number of workplace elections won by unions reached a seven-year high. And public approval of unions stands at 71%, according to a Gallup Poll last year, the highest since 1965.

Despite all this momentum, many newly organized workers have failed so far to win the most important thing: a contract. Many companies are dragging their feet when it comes to bargaining.

“Obviously, their strategy is this: ‘We will not sign a collective bargaining contract. ... We will wait for the next turn of the economic cycle when there is a recession or something,’” says Nelson Lichtenstein, a historian and director of the Center for the Study of Work, Labor, and Democracy at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Absent a change in labor laws, which would tilt the advantage back in unions’ favor, a rebound looks unlikely, he says.

“The courts and maybe the Congress and certainly the managerial mindset could shift,” he adds. “When you talk about union upheaval – or other upheavals – usually the elites make concessions because they think concessions are the lesser of two evils. So you think that communism is sweeping the country in 1937? Let’s recognize some unions because there could be a rebellion. And if you think that urban riots are going to progress even more in the ’60s, we’d better offer some civil rights laws.”

From management’s perspective, unions often represent a large – and unnecessary – interference in company-employee communication and problem-solving. “Waffle House is proud of its long record of effectively addressing concerns our Associates report to us,” the company said in a statement to the Monitor. Senior managers have met with workers at the Columbia restaurant. “We’ve already carried out work on most of the issues that were discussed, and we are working on others.”

Generally speaking, employers are not sounding conciliatory, even those who have seen unions organize small parts of their operations.

“The direct relationship we have with our partners [workers] enhances our ability to anticipate and meet our partners needs, provide opportunities for their success, and is fundamental to who we are and to the success of our business,” Starbucks said in a statement to the Monitor. “We respect the right of the 3% of stores that have opted for union representation. ... [But] as a result of the direct employment relationship preferred by nearly 97% of our partners, we continue to work to reinvent and improve the Starbucks experience.”

Ms. Parker, at Waffle House, has noticed a change since her mini-strike. “My coworkers, some of them have been very against what I did. And the atmosphere among managers is very different now, I’ll leave it at that,” she says. “But everybody is paycheck to paycheck, and the cost of living is high. ... I’m going to keep pushing.”

Staff writer Ali Martin contributed to this story from Los Angeles.

Editor’s note: The status of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union’s tentative six-year contract has been clarified.