What not to do with tax money

Loading...

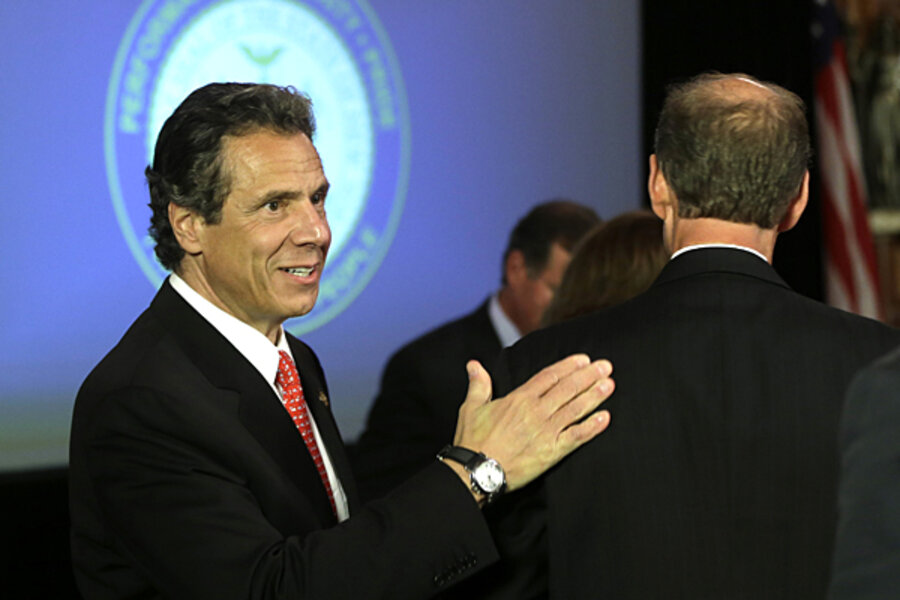

After years of grim revenue news, state tax collections are surging. As they do, governors and state legislators are making decisions about how to manage the unfamiliar windfall. Some governors, including California’s Jerry Brown, are husbanding resources, trying to hold down spending and paying down one-time debts. Others, such as New York’s Andrew Cuomo, are falling victim to the siren song of targeted tax cuts.

Cuomo is not cutting tax rates across the board, like some Republican governors. Instead, he’s doubling down on a strategy of growing the state’s economy through targeted tax breaks even though there is little evidence that previous economic development subsidies paid off.

START-UP New York (SUNY Tax-free Areas to Revitalize and Transform UPstate New York), under consideration by the legislature today, would give businesses and their new employees ten years of tax breaks if firms open in specific areas designated on or near public college campuses. Employers would be exempt from corporate and property taxes (for the new business) and receive refunds for sales taxes. New workers at these firms would be exempt from personal income taxes on wages earned at the firm for five years and exempt from income taxes on income below $200,000 for another five.

Cuomo insists the subsidies would attract businesses from other states or lead to new businesses sprouting up. But researchers have found that targeted tax cuts rarely do that. While taxes matter, businesses make location decisions for many reasons, including infrastructure and labor force qualifications. Cuomo argues that while New York colleges and universities receive the second highest amount of research dollars (after California) they get much less private investment. And there is much less interest on the part of venture capitalists (as compared to California and Massachusetts). Of course, some might argue that the investment in these other states is more about the type of research underway at the schools rather than incentives from state government.

Another problem is that location-based tax breaks tend to move existing jobs around rather than creating new ones. If I’m thinking of starting a business in New York and can get a tax cut for setting it up in one building rather than another one in the next town over, I may do so. But it’s not clear I’ve created many more jobs in the process.

An existing economic development jobs program – called Excelsior Jobs – has produced disappointing results so far. But instead of going back to the drawing board the new plan would double down, by halving the required net new jobs (from 10 to 5) while increasing the size of the incentive (from 2 percent of a qualified investment to 5 percent).

Cuomo responded to earlier concerns about tax-free zones by refining the bill. He’s excluded location-driven businesses, including retail, real estate, and professional services. Benefits would go only to firms that move into specific properties. And he’d deny benefits to firms that merely move existing jobs to the tax free zones without creating new ones, though preventing such gaming is not easy. For instance, will these denials hold when the first business threatens to move to Connecticut if it doesn’t get the tax breaks? And what do the employee income tax exemptions mean for new vs. existing employees, will existing firms need two pay scales based on income tax requirements?

Not only would the plan cost the state revenues but it could also drain the coffers of local governments that rely heavily on property taxes. College towns already lose revenues because land owned by non-profits and the state are exempt from property taxes. If businesses set up in Cuomo’s new tax-free zones, local governments will take yet another hit.

And that’s what happens to places that are lucky enough to get the new businesses. What of the New York cities and counties that lose firms to college towns? They also stand to lose revenues in what is likely to become a zero-sum game.

Which brings us back to California, where the un-Cuomo Brown presides. He’s proposing to curtail enterprise zones through narrowing eligibility for hiring and sales tax credits, recognizing that such programs often just move money around without increasing economic activity. California is trying to offer some targeted tax incentives for businesses but a more promising model for New York might be their California Competes program of increasing degree attainment and performance of students, rather than trying to pick winners and losers.

In December 2011, I credited Cuomo with a tax plan that his legislature passed in two days and that ensured the state had enough money, while Brown needed to wait almost a year to see if voters would approve his new taxes (which they eventually did).

But Brown gets my vote now for better policymaking. While there is additional money in the California budget for the first time that I can remember, he’s taking the long view. Maybe it’s just because he’s been around long enough to remember surges in short term revenues often disappear.