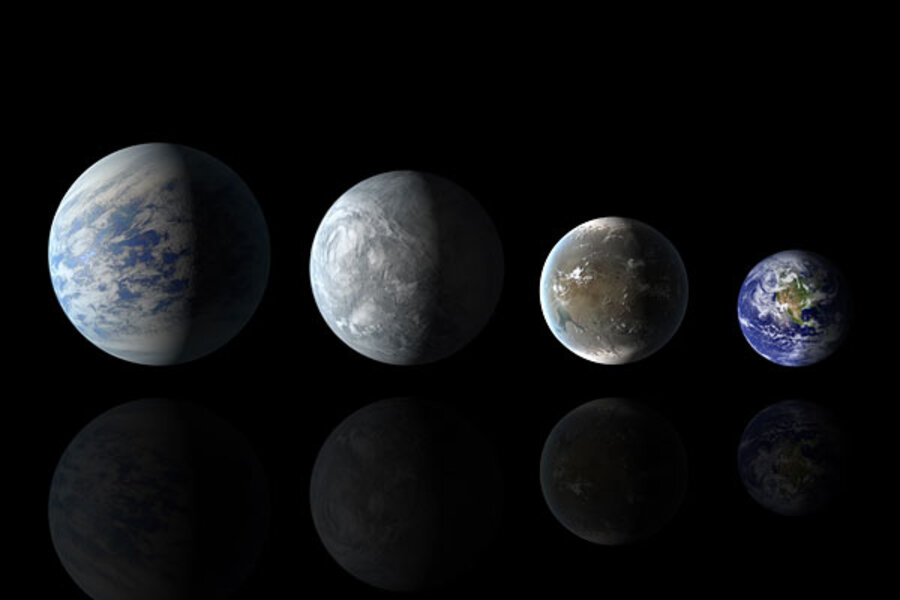

If Kepler-22b was the first and most Earth-like planet-candidate found by Kepler, then two of the planets in the Kepler-62 system represent a further refinement.

Like Kepler's first "Goldilocks" find, Kepler-62e and 62f are in their star's habitable zone, which is closer to the star than ours because Kepler-62 is only two-thirds the size and mass of our sun. The planet Kepler-62e makes an orbit once every 122 days, while 62f makes an orbit every 267 days.

Both are also larger than Earth: 62e is 60 percent larger while 62f is 40 percent larger. Current models suggest that planets more than 50 percent larger than Earth tend to be more watery, leading to speculation that 62e might be an ocean world. Meanwhile, models of 62f suggest it might be rocky, though both are too far away to get an accurate mass estimate, which would offer clues as to their composition.

For its part, 62f is on the outer edge of the habitable zone, meaning it would likely need to have a strong greenhouse effect to be warm enough for liquid water and life.

The discovery of these planets, along with a super-Venus in the Kepler-69 system, were announced in April. Kepler-69c is 70 percent larger than Earth and is dubbed a "super-Venus" because, like Venus, it is on the inner edge of its star's habitable zone.