Scientists one step closer to a working quantum computer

Loading...

Building a quantum computer can be tricky.

Unlike classical computers, which store information in bits, or binary digits represented by 0 or 1, a quantum computer uses qubits, or quantum bits to store information. A qubit can have a value of 0, 1, or both at the same time, potentially allowing quantum computers to solve certain problems – such as searching databases or factoring prime numbers – far faster than their classical counterparts.

But building a computer with subatomic components is challenging, to say the least.

Scientists have now developed a "five-qubit array" that could bring us one step closer to the first fully functional quantum computer. The findings of the study appeared in the journal Nature on Thursday.

"Quantum hardware is very,very unreliable compared to classical hardware," Austin Fowler, a staff scientist in the physics department, and a co-author on the paper said in a press release. "Even the best state-of-the-art hardware is unreliable. Our paper shows that for the first time reliability has been reached."

Quantum computers are made up of thousands of qubits. For the computer to function, the qubits need to be arranged in a two-dimensional array. Through quantum entanglement, the qubitsform a "logical state" that, to work properly, needs to have a low error rate. It is difficult to achieve such an arrangement because qubits themselves are faulty, said graduate student and co-lead author Julian Kelly, who worked on the five-qubit array project. Therefore, error correction is necessary.

The researchers reduced the error in controlling individual qubits to the levels required for error correction. "This paves the way for creating logical structures with low cumulative error using many entangled qubits," lead author Rami Barends, a postdoctoral fellow with the group and Kelly wrote in an email.

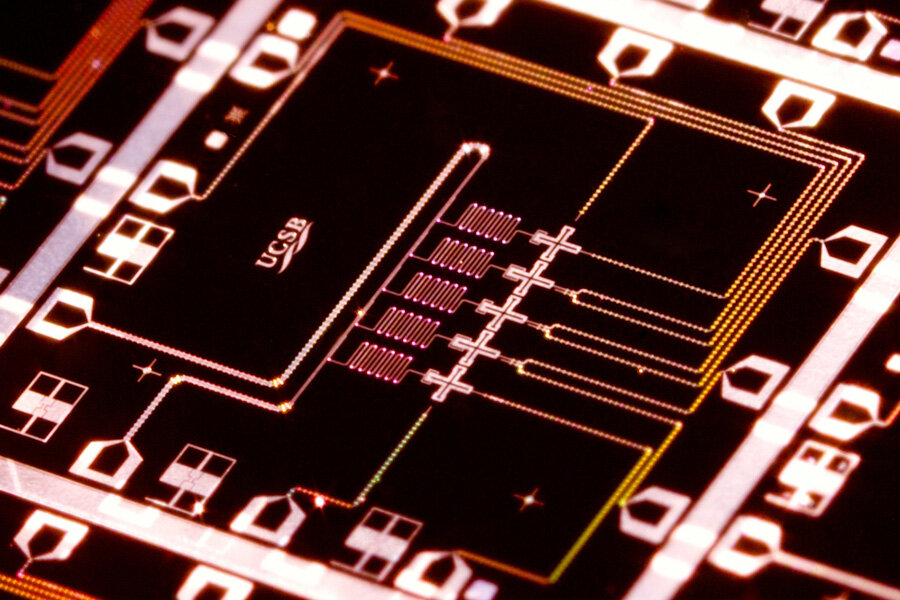

They built the qubits in certain geometrical shapes that could be controlled, coupled, or isolated on demand. Five cross-shaped qubits named Xmons were placed in a single row to ensure that each one talked to its nearest neighbor.

Scientists achieved this "threshold of performance of the qubits" which arranged in a five-qubit array model can operate with an acceptable margin of error. Also, the probability of the state of one qubit disturbing the state of a neighboring qubit is extremely low, a necessity for building larger arrays.

But we are still a long way from having a fully functional quantum computer.

“If you want to build a quantum computer, you need a two-dimensional array of such qubits, and the error rate should be below 1 percent,” said Dr. Fowler. “If we can get one order of magnitude lower — in the area of 10-3 or 1 in 1,000 for all our gates — our qubits could become commercially viable. But there are more issues that need to be solved. There are more frequencies to worry about and it’s certainly true that it’s more complex. However, the physics is no different.”