Bye-bye Rosetta: Why scientists crashed the famed comet-explorer on purpose

Loading...

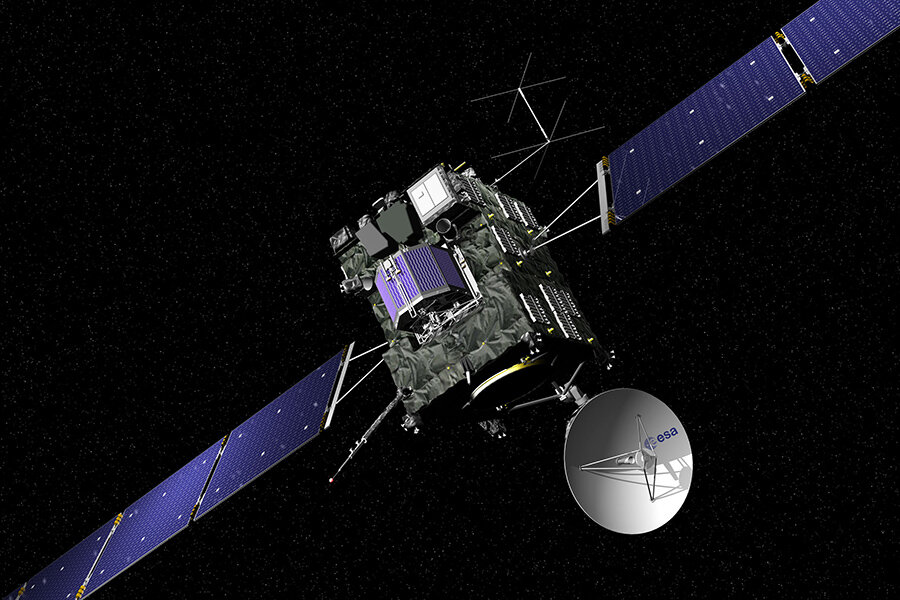

The European Space Agency’s Rosetta spacecraft crashed into the comet it has spent its life faithfully studying on Friday morning – intentionally.

The European Space Agency (ESA) launched Rosetta in 2004 to study the composition of comets, a lesson that scientists hope will contribute to their understanding of how the planets, including Earth, were formed.

Over the past 12 years, Rosetta has followed comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko across more than 3.7 billion miles of space, sending data and photos back down to Earth. After finally reaching the comet in 2014, Rosetta released Philae: a smaller probe that performed the first-ever comet landing.

During their tour of the comet, Rosetta and Philae provided a wealth of new data to scientists.

"We have learned a lot about comets," ESA’s Markus Bauer told The Christian Science Monitor in February. "We had to learn for example that the water on comets is not the same water as in Earth’s oceans. Our water must therefore have come from other sources. We have discovered organic compounds which play a key role in the prebiotic synthesis of amino acids and sugars, which are the ingredients for life."

And, as Manuela Braun of the German Aerospace Center told the Monitor’s Jason Thomson, scientists previously expected comets’ surfaces to be soft and fluffy. But as Rosetta and Philae’s missions have proven, a comet’s composition can be “very heterogeneous” with hard surfaces.

“It will be hard to see that last transmission from Rosetta come to an end,” Art Chmielewski, of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and project manager for the US Rosetta, said in a press release. “But whatever melancholy we will be experiencing will be more than made up for in the elation that we will feel to have been part of this truly historic mission of exploration.”

But Rosetta’s fatal crash course was not the only option.

“We could have abandoned it in space or let it bounce off the comet and just switched it off. It wouldn’t have created any problem,” Andrea Accomazzo, the ESA's spacecraft operations manager, told The Guardian. “Landing is more a psychological thing.”

However, Rosetta was set to end one way or another. The comet 67P is racing toward the outer solar system – a destination too far away from the sun for a piece of solar-powered machinery.

And even in its final hours, Rosetta sent crucial information back down to Earth by taking close-up photos and “once-in-a-lifetime measurements” of comet 67P. Specifically, Rosetta focused on one-meter high lumps, or “goose bumps,” in an open pit of the comet, which have puzzled scientists for years.

“We want to go out at the peak of capability. We don’t want a comeback tour that’s rubbish,” project scientist Matt Taylor told Reuters. “We will end in a very rock-and-roll fashion.”

This report contains material from Reuters.