Video game museum gives arcade classics extra lives

Loading...

| Laconia, N.H.

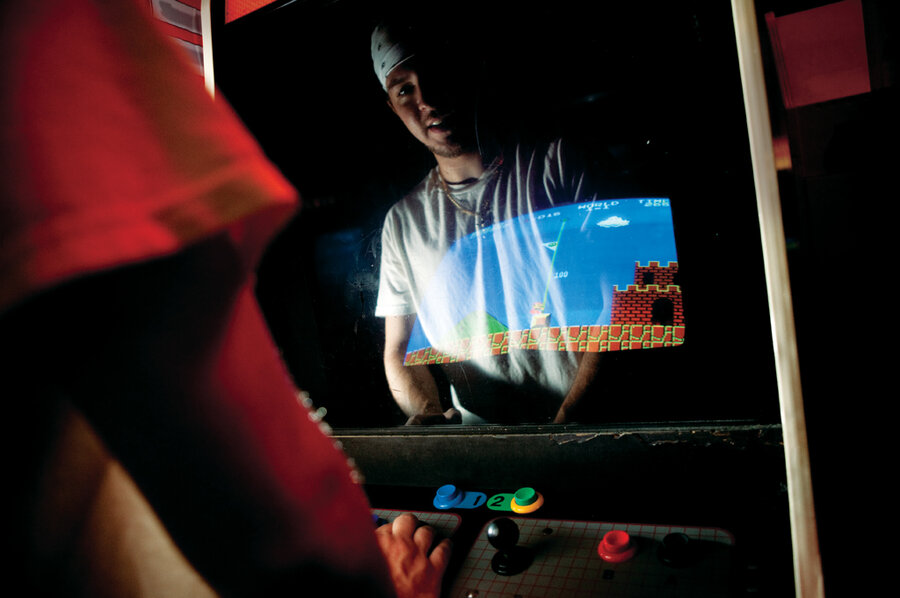

Downstairs at Funspot, the venerable amusement center here near the shores of Lake Winnipesaukee, tourists arrive in waves to play air hockey, ride the bumper cars, and pump tokens into modern video games such as Dance Dance Revolution and Terminator Salvation.

But upstairs, the dim, cavelike American Classic Arcade Museum (ACAM) creates another reality. Period music – Toto, Men at Work, Duran Duran – trickles in, mixing with the electronic beeps, zaps, and chirps of machines arranged in long rows like a robotic army. Among this array of classic arcade games, the largest in the world, you'll see classics such as Pac-Man and Space Invaders, but also rare finds such as Quantum and even Pong, the only one still on public display and playable.

Here, time has screeched to a halt. Neither the games nor the music is younger than the final year of the Reagan administration.

Double Dragon came out in 1987, "around the time that things began to change," says Gary Vincent, the museum's president, who opened it in 1998 and grew the arcade's collection to some 280 video games. As the first nonprofit dedicated to preserving coin-op amusements, ACAM is a sort of living history museum of gaming culture.

"The games don't make much money," Mr. Vincent says. But money is hardly the point. Unlike at other museums, here you can touch. Every game on the floor is there to be played. And for 25 cents, the museum lets folks try to revive their old-school gaming mojo.

As gamers get older, there's been a resurging interest in arcade classics. This nostalgia trip hit the public consciousness with the 2007 documentary film "The King of Kong: A Fistful of Quarters," which offered a peek into the world of retro video game competitions. Since then, the subculture that exults these games has broadened beyond a dedicated few. Gradually, a movement to collect relics from the medium's history has gained traction. Academic institutions and individuals have begun archiving them. But preservation isn't simply a sentimental effort to relive people's digital childhoods. These games offer a unique window into the cultural and social impact of video games.

"Quite simply, digital games are a part of contemporary culture," says Henry Lowood, curator of Stanford University's History of Science and Technology Collections and Film and Media Collections, in an e-mail interview. "If we care about understanding our culture, we have to care about preserving its history, and games are a part of that history." Similar institutional efforts to gather video games and memorabilia are housed at the University of Texas at Austin and the Strong National Museum of Play in Rochester, N.Y.

Mr. Lowood also spearheads the "game canon" project, a list of video games slated to be preserved by the Library of Congress. A committee of game developers and experts chose the first 10 games: from 1962's Spacewar! (considered to be the first computer game) to Tetris and Super Mario Bros. 3.

Conservation is also paramount for practical reasons: Arcade hardware is fragile. The games themselves were programmed into the circuit boards, and if those fail, the games die.

The preservation movement shows not only how far the technology has progressed, but also how much public perception of video games has changed. "This game generated its own 20-minute segment on '60 Minutes,' " says Vincent, standing in front of Death Race, one of the museum's crown jewels. The driving game involves cars running over "gremlins," which in their pixelated form looked like pedestrians. In its day it was vilified as much as heavy metal music and Dungeons & Dragons. With its blocky, stick-figure, white-on-black graphics, it now seems laughably primitive, and as tame as a hayride. "These days on PlayStation, it would be rated 'E for everyone,' " he jokes.

Many classic gamers are now in their 40s, and some still prefer playing in arcades over playing in their living rooms. Donald Hayes – whom Vincent calls "probably the best classic game player ever" – finds new Xbox games uninteresting. He is drawn to the "simplicity" of classics. "They don't depend on the graphics," says the software engineer from Salem, N.H. "The Xbox controller has, like, 20 buttons. The old games, it's a joystick and a couple of buttons."

Mr. Hayes holds several high-score world records, including being one of only six people to get a perfect score in arcade Pac-Man. He also holds records in Joust, Centipede, Millipede, Super Zaxxon, and several others. At Funspot's Annual International Classic Video Game Tournament, which draws between 150 and 175 competitors, Hayes defends his good name. Currently, he's training to reclaim his old Dig Dug and Frogger records. "There's a lot of work involved," Hayes says. For example, setting the Centipede record took him nine hours of continuous play; Dig Dug takes 12 to 15 hours. Hayes goes to Funspot once a month to practice. He also owns 12 arcade machines.

Another option for those interested in upping their old Ms. Pac-Man scores: Wii Virtual Console and Xbox Live Game Room, online services that let players enjoy classics such as Asteroids, Tron, and Missile Command at home. There's also a site called mamedev.org, whose "Multiple Arcade Machine Emulator" reproduces games as faithfully as possible for the modern computer.

But what's lost in playing arcade games at home is the social experience. "You could go to the arcade and see your older brother's score from the night before," says Christopher Grant, editor in chief of the video game blog Joystiq and a member of the game canon committee. "When we're talking about game preservation, we're not just talking about the game. We need to preserve the player." Some home console games now have online leader boards, so that social experience is coming back.

There's also the camp that argues that a crucial game-playing experience disappeared when game designers began creating realistic, immersive game environments such as World of Warcraft. To Chris Kohler, video games editor at Wired.com and a devoted games collector, 8-bit-style games are easier to understand, more accessible, and don't require the dedication of a 3-D, first-person shooter game.

Mr. Kohler's Game|Life blog regularly lists the various Commodore 64 or Amiga cartridges he's unearthed at tag sales and thrift stores. "2-D wasn't archaic. It was in fact a superior way to design games. Or if not superior, a unique style that needs to be preserved." A new generation of programmers is answering this call and designing retro games that mimic the look and feel of these arcade games of yore.

"I am sure that for some retro-gamers, stripping away the surface layers associated with modern games gives them the feeling of being closer to something we might call core game-play," says Lowood.

So if these arcade games aren't necessarily about over-the-hill gamers trying to recapture their past arcade glory, perhaps they succeed in returning players to simpler purity. They even evoke a misplaced nostalgia for a time that a gamer may not have personally experienced: Mark Hazelton, age 24, of Sandwich, Mass., visited Funspot with his sister and niece for the third time in four days. "There are a lot of games here I grew up on," he says. "It's like nostalgia. All the new games are crazy-good-looking. But I like coming here. They even have Pong here from 1972. It's cool they have that."