Chicago school closings: Shuttering these institutions is shortsighted, says one local mom

Loading...

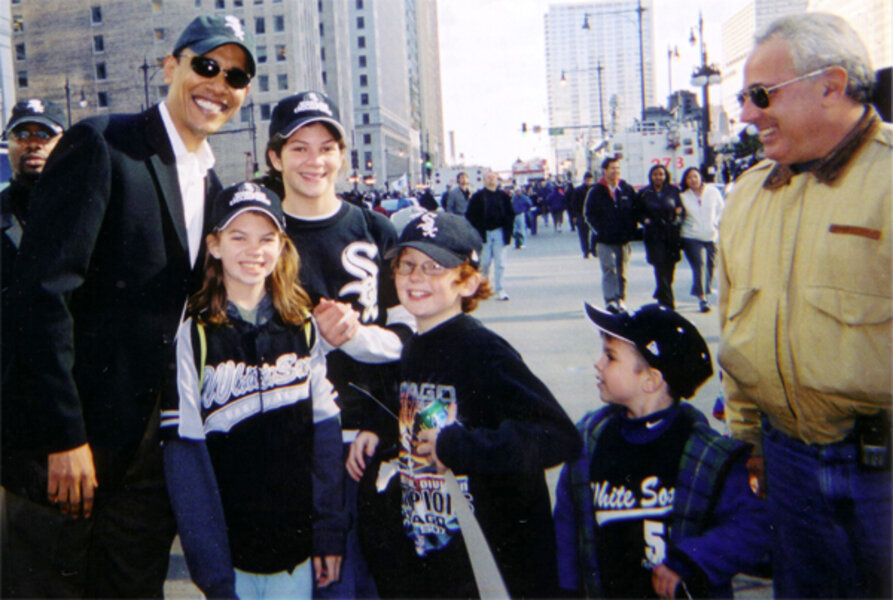

In my neighborhood tonight, chaos will reign. My neighbor, President Obama, will be staying in his part-time home just around the corner from me in Chicago. His occasional visits bring limited parking, random ID checks, and bomb sniffing dogs to our front lawn.

But on warm summer nights, the street takes on a carnival-like atmosphere. Neighbors come out to chat and I sometimes get to meet people from the next block. The Secret Service agents are friendly enough, and when the barricades go up and traffic halts, people get out of their cars to stretch and enjoy the novelty of the president driving down this normally quiet residential street. More often than not, we recognize someone and invite them to join us for a drink on our stoop.

It can be inconvenient if you happen to be walking your dog without identification. But he was once our neighbor, and it’s all a part of living in this neighborhood.

But I’m not feeling all that benevolent these days, and I may forego my usual stoop-sitting tonight. The truth is, a much more serious chaos has reigned in too many of Chicago's communities following last week's announcement that 50 Chicago neighborhood schools would be closed.

The closings made national news briefly, just like the murder of Hadiya Pendleton, the sparkly teen wielding a baton in the inaugural parade for President Obama, her Chicago neighbor. She was also a neighbor of mine and lived about a mile from my and the president’s homes.

Since Hadiya was killed in late January, the murders of 26 more teenagers did not make the news. Similarly, the brief blip last week about the largest number of school closings in the history of the country does not recount the anguish and dismay of 30,000-plus children and parents scrambling, wounded, and angry.

In Chicago, we grew up hearing that Chicago is “a city of neighborhoods,” a patchwork of tightly knit, culturally distinct, and ethnically proud communities that together make up our city. While this may be an idealized re-definition of segregation, no matter where you live, you belong to a community. This attack on the most important of neighborhood institutions has left us collectively demoralized. We see ourselves on the nightly news, segregated, characterized by crumbling schools and random violence.

Despite our pride at the notion of being a unique “city of neighborhoods,” people all over the country know about community. It’s sometimes hard to describe as it shifts imperceptibly over the years. But we feel it, and we are bound to protect it.

The divide-and-conquer strategy of closures pits school against school. In this latest round, the initial hit list of 230 schools was pared to 120, then to 61, and eventually 50, while everyone waited anxiously, breathing a sigh of relief if their school was taken off the list.

Sadly, our neighborhood middle school was not spared, although its closure was postponed for one year so the current class could graduate. Miriam Canter Middle School was named for a local activist who envisioned a racially and economically diverse school dedicated to kids precariously perched between childhood and full-fledged teen madness. Many of the devoted teachers at Canter live in the community. Last month, an article in The Nation recounted the hearings that drew hundreds of weeping teens, angry parents, and concerned community members demanding to know why they would close such a clearly successful school.

This scene was played out all over the city. But then something happened – something that happens when communities feel threatened. Instead of feeling isolated and under attack, parents from closing schools organized, talked to each other. They began with a series of marches, challenging Mayor Rahm Emanuel to “walk the walk” their children will have to walk to their new schools. The mayor didn’t show, but parents from around the city went from school to school in solidarity, sometimes 300 showing up in a neighborhood they may never have visited before.

They were retired teachers and students; union members supporting the thousands of lunchroom workers and engineers who would lose their jobs; grandmothers marched beside pierced and tattooed Occupy students; and parents of children in elite “selective enrollment” schools not on any hit lists who came carrying signs saying “Every Chicago Public School is My School.”

I marveled every time I participated in one of these events. These people rallied because they know the binding institution in any community is the neighborhood school. This is known by businesspeople, promoted by real estate agents, accepted by children, and desired by most people.

The Board of Education says that demographics have changed, money is not there, and school closings are inevitable. They cluck sympathetically that “change is hard” in a tone so condescending I wouldn’t dare try it on my teenager. But I suggest to them that they are the ones who must change.

For example, they did not visit Matthew Henson Elementary School, a so-called “underutilized” school with a population that is 100 percent low income, where 12 percent of the children are homeless. Chicago Public Schools (CPS) officials say it is only 32 percent utilized. However, in the “unused” classrooms, they have a parent resource center, a computer lab, a science room, a music room, a library, a full-service health clinic, and a visiting food pantry. Another classroom is used for small group interventions, and yet another serves as after-school space for teens.

When Henson closes, not only will the receiving school become overcrowded but these vitally needed services will not be available to the community.

Is this not shortsighted? Once upon a time in the baby boom years, this school may have adequately served a much larger population. I would argue, whatever the population’s size, this school is adequately serving the needs of the community.

Unlike the Lawndale neighborhood where Henson is located, people in my neighborhood have a lot of choices when it comes to schools. In addition to quality public schools, we have a Montessori school, the elite University of Chicago Laboratory School (once attended by the Obama girls, schools chief Arne Duncan, and now Mayor Emanuel’s kids), and a Catholic school. One of the reasons we were unsuccessful at keeping Canter open was that many of the students were from outside the boundaries. They come to this school from other neighborhoods because it is a safe school in a safe neighborhood.

As a community we welcomed them, but now we’re told that we cannot.

The thousands of people fighting against this know it’s not about boundaries and numbers, it’s about what unites a neighborhood and how they relate to the one institution. Many of these schools are uniquely suited to the neighborhood and population.

What’s happening is more than a news blip. The one-room schoolhouse changed with the changing needs of the population. It’s time to seriously rethink how neighborhood schools and public education align with the democratic principles of freedom and inalienable human rights.

I know... change is hard, but it’s time.