How to teach your kids to love poetry (Hint: fall in love with it yourself)

Loading...

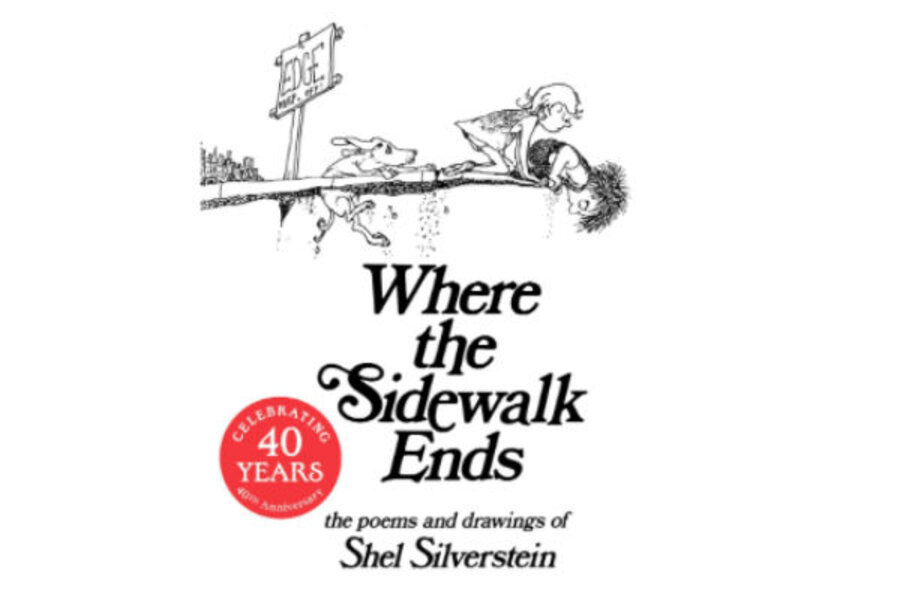

Like many of you, my love for poetry began with Shel Silverstein. I can still remember the long waiting list to check out “Where the Sidewalk Ends” in elementary school.

When it was finally my turn and they placed the white and black hardbound book into my eager hands, I felt like I’d won the lottery. It was a treasure, and I was already mourning the day I’d have to pass it along to the next lucky kid in line.

Now, at age 38, the silver spine of my very own copy, the thirtieth anniversary edition, peeks out from the bookshelf. I catch it smirking at its neighbors every now and again. “Seek and Find Shrek” and Dora’s “A Puppy Takes a Bath” have enough sense to know when they’ve been bested. They remain quiet and endure the smirk, happy to bask in the afterglow of another’s greatness.

Silverstein’s poems transcend age and time. They are beloved by adults and children alike and remain for me today just as delightful as they were thirty years ago. From time to time, we pull the book from the shelf and read a few selections as a family.

A few years ago, my husband started writing Silverstein-esque poems for our kids. These poems are most often about animals getting into one kind of mischief or another. There's Matilda the Moose who likes to knit with strange materials, Dave the Dingo who has unfortunately acquired a bad reputation at school, and of course, my all-time favorite, Chris the Cricket who, I’m sorry to tell you, meets an unfortunate and chocolatey end. These poems very often end with belly laughs and happy tears, and, inevitably, our children begging their father to read, "just one more! Please!"

My real love for poetry as an adult came when, as a participant in a writer’s workshop, I heard a poet read her work aloud. I was there to study nonfiction, and every evening participants gathered to hear their peers and teachers read work from their selected genres.

As I listened to Solmaz Sharif read her poem “Personal Effects” I was overcome by the musicality of it; by the power of well-chosen words and rigorous intentionality. It was a dance and I was invited to participate. I looked around the room to see if everyone else was as dumbstruck as I was. I was in love and I think it was because she was in love.

After the writer’s workshop, I began to try on different poets. I was desperate to find another connection to a poet like the one I had experienced with Sharif. I borrowed “The Poets Laureate’s Anthology” from our local library. There were some poems I liked immediately, some I had to work harder to access, (reading and re-reading), and some I didn’t understand at all.

One afternoon as I sat on the couch browsing the anthology, I came across Kay Ryan’s poem, “Things Shouldn’t Be So Hard.” With each line, a chord struck,

“A life should leave

deep tracks”

and then a hum began in my veins.

“where she used to

stand before the sink,

a worn-out place;”

The tiny hairs on my arms stood on end and my throat began to close,

“The passage

of a life should show;”

and as I reached the final line,

“Things shouldn’t

be so hard.”

My 8 year-old daughter walked into the room to see me spit joy and tears and grief all over the living room carpet.

“What’s the matter, Mom?” she asked.

I swiped at my nose and blotted at my face. “A poem, that’s all,” I said. She smiled, relieved nothing was wrong. “Want to hear it?” I said.

We sat together, on the couch, and I read Kay Ryan aloud. When we were finished, my daughter ran up to her bedroom to grab a notebook so she could compose some of her own lines. She fell in love because I was in love. Those fifteen minutes spent on the couch together taught her more about poetry than any eight-week curriculum could have.

We didn’t study poetry to tick the boxes of an imagined cultural syllabus. Rather, we snuggled up together and fell in love with the words.

Part of teaching our children to love poetry is falling in love with poetry ourselves. Does that mean I don’t worry about teaching them the different forms and mechanics? Certainly not. In fact, I recently came across the beautifully illustrated book, “A Child’s Introduction to Poetry,” which not only explains the different poetry forms, but also exposes children to poets such as Dylan Thomas, E.E. Cummings, and Seamus Heaney. The book also provides an audio CD so children can hear the poems read aloud.

So, while it’s true great poems come as a result of a mastery of the craft, hard work, and patience, in the beginning I simply encourage my children to enjoy the words, and I cheer them on as they dare to scribble down their own lines.

In an age when information is delivered in a quick manner, an assault of facts concise and direct enough that we don’t have to give them much thought, some may question the value of information that we must slow down to process. Truth and raw human emotion can be delivered in a manner of ways, however, and sometimes the best path is not the most direct. I am reminded of an excerpt from a poem by Brian Doyle in which he addresses the question he received from a kindergartner, “What do poems do?”

“My mind this morning was what do poems do? Answers: swirl

Leaves along sidewalks suddenly when there is no wind. Open

Recalcitrant jars of honey. Be huckleberries in earliest January,

When berries are only a shivering idea on a bush. Be your dad

For a moment again, tall and amused and smelling like Sunday.

Be the awful wheeze of a kid with the flu. Remind you of what

You didn’t ever forget but only mislaid or misfiled. Be badgers,

Meteor showers, falcons, prayers, sneers, mayors, confessionals.

They are built to slide into you sideways. You have poetry slots

Where your gills used to be, when you lived inside your mother.

If you hold a poem right you can go back there. Find the handle.

Take a skitter of words and speak gently to them, and you’ll see.”

Poems bring us truths that slide into us sideways. And though my youngest children are not ready for Solmaz Sharif or Kay Ryan (for now they are content to sit and listen to poems about hippopotamus sandwiches and sharp-toothed snails that live inside your nose), someday they will be. When that day comes, it will be my great privilege to invite them to the dance.