Three water garden design ideas from the Getty Center

Loading...

Recently, I gathered three great water design ideas while on a short walk. In Los Angeles I joined a docent-led tour down the hillside in the Central Garden at the Getty Center.

I had seen photos of the famous Bowl Garden [see first photo above], the round pool designed by Robert Irwin, where clipped azaleas appear to float in a complicated pattern on the water. (They’re in planter boxes separate from the pool.)

But what I really wanted to experience was the stream that leads down to the Bowl Garden. Here’s what I discovered:

Tip No. 1 – Zigzag the pathway

Streams are usually designed with pathways next to the water for close-up enjoyment. But the Getty’s steep hillside had to accommodate visitors, some of whom use wheelchairs, so the museum’s pathway had to have a gentle incline.

The solution to that design problem is elegant. The water flows straight down the hill in a narrow canal lined with square cobbles of rock. [See second photo above; click on arrow at right base of first photo.] The concrete path zigzags back and forth across the hill, continually crossing the rushing water in the center by a series of bridges.

What a wonderful idea. It’s visually exciting to keep turning toward the splashing rill and then walking away from it. The sound of the stream fades away as you leave it and then returns as you reach another crossing.

In a home garden setting, would it be possible to create a path that zigzags back and forth? Especially on steep slopes, a little engineering could be added for both comfort and pleasure.

Design Tip No. 2 -- Change the rock size as the journey progresses

At the beginning of the stream, the first rocks are as big as children’s playhouses. They’re so big that they jam the cobbled bed so that you can’t even see the moving water. But you can hear it. The splashes echo like a cave, once again reminding you to listen and enjoy.

At each bridge more of the stream is revealed as the rocks get progressively smaller. On the next crossing, the rocks are wheelbarrow size. You can glimpse the water rushing around them.

The sound changes as the boulder size is reduced. [See photo at left.] Under the last bridge, the stream flows freely [see second photo at left] and almost silently over a bed of small stone rectangles, the surface barely rippling.

Even on a much smaller scale in a backyard, you could use this idea of ever-changing rock size. Under the right circumstances, it might be brilliant. These are the same elements that make up any artificial stream, but you’re ordering them in a more conscious way.

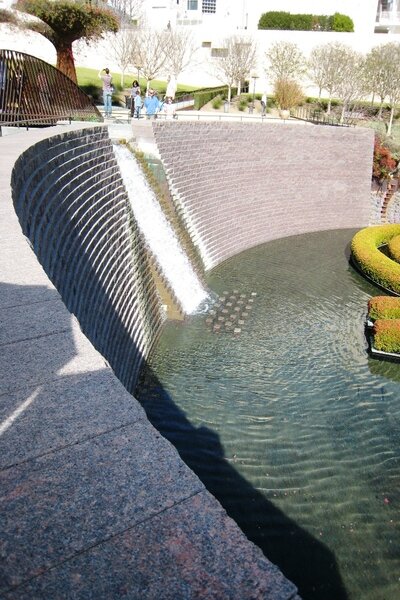

Tip No. 3 -- Divide the waters

Right before the Bowl Garden, a final bridge [see third photo above] with arching metal side rails hides a change worthy of a magician’s trick. It appears that the water flows under the bridge and then pours down a large spillway to the round azalea pool below. [See third photo at left.] It doesn’t.

According to Lorrie Levin, a museum docent, the water in the rill is treated with algaecides to keep it clear and the rocks clean. Those chemicals would never do in the azalea pool. So under that last bridge, a pump pushes the rill water back up the hill, while another pump brings pool water up and over the spillway to create the dramatic waterfall. The bridge allows the illusion of a continuous flow.

This kind of division could be very useful in a home situation. Natural streams could appear to flow down to treated water in swimming pools or hot tubs. Or, as at the Getty, the stream could be kept free of algae, whereas the pond below would be safe for plants and fish without the addition of chemicals. Biological filters and other equipment can also be hidden under bridges. Creating an illusion of joined water opens up many possibilities.

Editor's note: If you didn't look at the photos as you read the blog post, enjoy them as a slide show of the Getty water gardens. There are three at the top of the page and three at left.

-----

Mary-Kate Mackey blogs regularly about water in the garden for Diggin' It. She is co-author of “Sunset’s Secret Gardens — 153 Design Tips from the Pros” and contributor to the 'Sunset Western Garden Book,' writes a monthly column for the Hartley Greenhouse webpage and numerous articles for Fine Gardening, Sunset, and other magazines. She teaches at the University of Oregon’s School of Journalism & Communication. To read more by Mary-Kate, click here.