The novel tale of a paperback

Loading...

Sometimes a book is more than just a book.

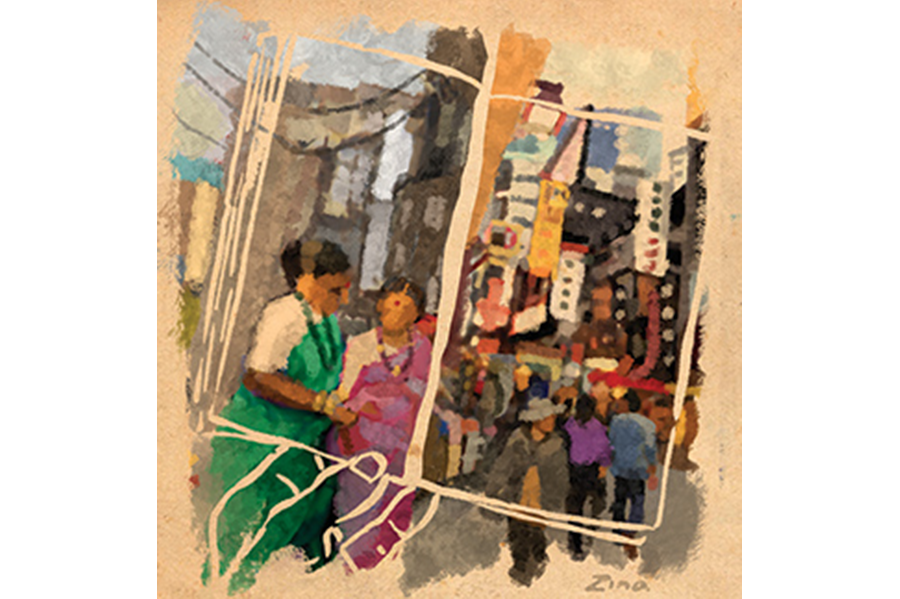

Consider the novel in which I am engrossed at the moment, a story set in Britain and India in the 19th century. It was written in English by an Indian author who now lives in Denmark, and although the paperback edition I’m holding was published in New Delhi four years ago, I (an American) purchased it recently from a secondhand bookshop in Tokyo.

That’s quite a history already. But there’s more.

The novel is a tale of myriad mysteries, all expertly woven into a seamless narrative by a very skillful author. Yet my particular copy presents even more mysteries than those embodied in the book’s plot and characters.

One summer morning in the year of my paperback’s publication – on July 15, 2012, to be precise – someone else was thumbing through it while eating breakfast in a restaurant in Colaba, the southernmost district of Mumbai.

I know this because I found a bookmark inside: a receipt for an omelet and caffè latte. I know that the bill – 286 rupees – was paid at 10:26 a.m., and I know which Indian bank issued the credit card used in the transaction. I even know the name of the waiter who served the meal: Raymond.

That, in itself, is interesting. But I also discovered that the owner of the paperback immediately before me was not the person in that Colaba restaurant that July.

In fact, the owner before me was not Indian at all, but Japanese.

I know this because throughout the book’s first 83 pages are handwritten notes in Japanese – translations of English words with which the reader was unfamiliar.

Japanese being a language of characters, not letters, it is not easy to determine if the note writer was a man or a woman. But the crispness and clarity of the calligraphy and the care taken to inscribe the translations neatly in the limited spaces available on each page all bespeak a woman’s hand.

So let us agree that it is a woman. What can we say of her? Well educated, clearly, and sufficiently fluent in English to feel adequate to the challenge of reading a novel written in a language other than her own. Probably young, or at least young enough to possess the discipline of a university student – someone who would keep a dictionary at hand while reading a novel.

But there are oddities here, too.

How did this young woman know the meaning of certain English words and phrases without having to research them? Although she looked up translations for “wharf,” “deportment,” “decapitation,” and “bluster,” for example, she did not require her dictionary to understand “accrete,” “languor,” “squalid,” or “burlap” – words that are hardly in common usage.

And why, after devoting so much effort to determining the meaning of so many words, did she suddenly stop? The last translation in my paperback – ironically, the Japanese characters for the word “tenacity” – appears on Page 83, less than a third of the way through the novel.

After that, nothing.

Did she give up because the book was proving too difficult? Did it demand too much of her time? Did her life circumstances change? A new job, perhaps? Or the birth of a baby? Did she simply lose interest? Or was there some other reason?

I am left with a raft of riddles. Who was the original owner of this book, eating an omelet and sipping a latte in a Colaba restaurant that summer morning in 2012? How did this paperback get to Tokyo from Mumbai? Who was the Japanese owner who dutifully looked up the words she didn’t know and wrote them down, to add to what was already a prodigious vocabulary? And why did she stop reading the book long before she had finished it?

I would love to find the answers, because I feel a connection with my fellow readers. After all, the three of us were captivated by the same story, and at least one of us made a herculean effort to understand it. But I suspect I never shall.

Many a novel presents enigmas, all of which are resolved by the end of the tale. The enigmas presented by my little paperback, however, defy resolution. They leave me to ponder endlessly the puzzles they embody – mysteries expertly woven into a seamless narrative, not by a skillful writer, but this time by the numberless vagaries of life itself.