Election’s over, but battle over its meaning is just beginning

Loading...

A week after voters went to the polls, the political class is engaged in fierce debate about what it all means. As more data emerges about vote breakdowns, partisans on the left, right, and center are struggling to frame the results in ways that reflect their beliefs and policy preferences.

It may be hard to distill the 2020 election into a few lessons. But a key one is that much of it revolved around incumbent President Donald Trump. Voters, tired of the chaos that has gripped Washington for the past four years, made choices that reflected what they believed needed to be done. President Trump continues to insist, without evidence, that the election was stolen.

Why We Wrote This

Knowing which candidates drew the most votes in last week’s election was Step 1. Now begins the work of interpreting the messages those votes sent, and shaping the U.S. political narrative.

In down-ballot races, Republicans did better than expected. On a post-election call with Democratic colleagues, moderate Rep. Abigail Spanberger of Virginia, who narrowly held on to her seat, said the No. 1 concern voters in her district mentioned was “defund the police” rhetoric. Progressive Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York pushed back, saying some members who lost neglected social media.

This tension is reflective of another trend revealed in the returns, says Professor Bruce Cain of Stanford University. “Both of the political parties are struggling with their core activist, heavily ideological bases.”

The just-concluded 2020 elections showed that America’s democracy remains resilient.

It was a rebuke of the liberal wing of the Democratic Party, given that President-elect Joe Biden, a moderate, ran ahead of many down-ballot Democratic candidates.

It was bad news for the whole Republican Party, whose loss of the White House portends a difficult future as the nation becomes more diverse in years ahead.

Why We Wrote This

Knowing which candidates drew the most votes in last week’s election was Step 1. Now begins the work of interpreting the messages those votes sent, and shaping the U.S. political narrative.

The takes above are all true – unless they aren’t, and democracy showed its flaws, moderate Democrats stumbled, and the GOP can take hope, given the makeup of its down-ballot electorate.

A week after voters went to the polls, the nation’s political class writ large is already engaged in fierce debate about what the election means. As more data emerges about vote breakdowns and voter demographics, those on the left, right, and center are struggling to frame the results in ways that reflect their beliefs and policy preferences.

It may be hard to distill the 2020 experience into a few key lessons – the electorate and politics in general is much more fractured than it was 50 or 60 years ago, says Bruce Cain, a professor of political science at Stanford University.

But a few themes are emerging. One central one is that much of the vote revolved around incumbent President Donald Trump – the man, and his values.

“A lot of us who have been around can say that not since Nixon has an election shook a lot of us to the core over whether our commitment to democratic values and fair play has eroded to the point where we are flirting with authoritarianism and undermining the integrity of our electoral system,” says Professor Cain.

A crossroads election

For its part, the Trump campaign is still contesting the most basic story about the 2020 vote: who won. Without evidence that stands up to scrutiny, President Trump continues to insist that the election was stolen and he is the real victor. Many GOP elected officials have declined to acknowledge Mr. Biden’s status as president-elect in deference to the incumbent’s wishes.

Trump allies have primarily questioned vote counts in Arizona, Georgia, and Pennsylvania. To date, most Republican legal efforts have been small-scale and many have been thrown out by judges.

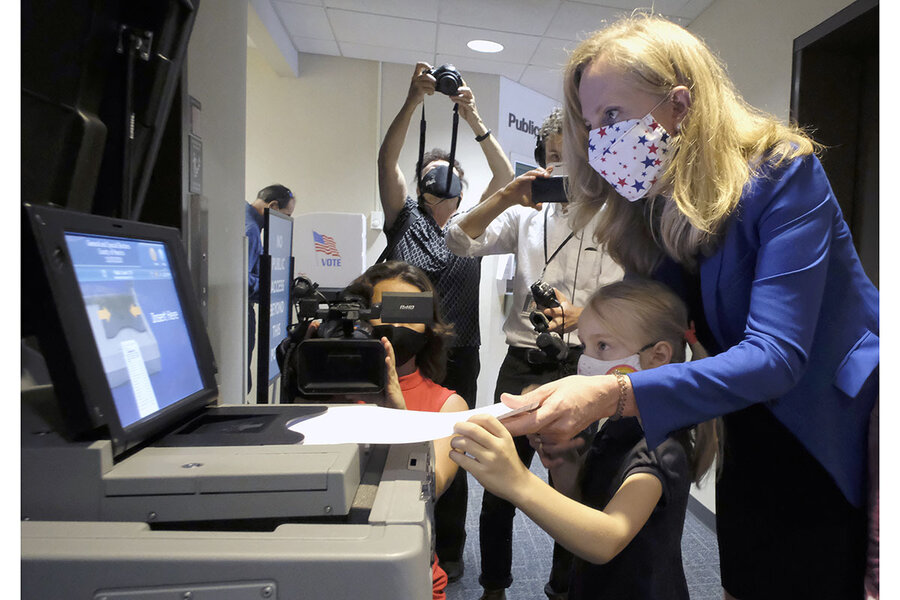

If there is one narrative about the election that all sides agree on, it’s that the turnout, driven by an explosion of interest in the presidential battle, was phenomenal. Final figures will likely show that the percentage of eligible voters who cast ballots will be the highest in 120 years.

One way to look at this is to see it as a triumph for democracy. Voters, tired of the chaos that has gripped Washington for the past four years, stepped up to their job and made choices that reflected what they believed needed to be done about the situation.

“People truly recognized that this was a crossroads election,” says Allan Lichtman, a distinguished professor of history at American University.

But what was the force pushing voters to the polls? It wasn’t both candidates, but only one of them, the incumbent president, and one emotion, fear. His supporters feared he would not win reelection. His opponents feared he would. The powerful polarization driving this is not itself positive for U.S. politics.

“It wasn’t Biden driving the turnout. ... It was Trump driving the turnout,” says Professor Lichtman.

President Trump motivated Bill Huggins to vote, for instance. The retired former manager for Black & Decker says he voted for Mr. Trump in 2016, and was enthusiastically voting for him again. “I’m for small government, the Constitution, and run the government like a business,” says Mr. Huggins, standing outside his polling place at the Shrewsbury Municipal Building on Election Day.

At the Cornerstone Baptist Church in York, Pennsylvania, Benita Howard also said the vote felt important and different to her this year.

Ms. Howard, who works as a nurse and voted for Mr. Biden, says the sentiment in the country has felt very bad for the past 1 1/2 years or so. She thinks the U.S. needs a change for the good of the people.

“I’m voting for equality for everybody. It used to be that the U.S. was looked at as the land of opportunity,” she says. “Where you could make changes for yourself and improve yourself and your family. And it doesn’t feel like that anymore.”

Democrats, divided

Perhaps the hottest down-ballot argument right now about the meaning of the 2020 vote is between moderate Democratic members of Congress and progressives.

With the party reeling from an unexpected loss of seats in the House, Democratic moderates are blaming the more liberal members of the party for pushing big government policies such as the Green New Deal, and especially for the “defund the police” push to reorient urban spending priorities.

On a postelection call with colleagues last week, Democratic Rep. Abigail Spanberger of Virginia, who narrowly held on to her seat, said the number one concern voters in her district mentioned was “defund the police” rhetoric.

“If we are classifying Tuesday as a success from a congressional standpoint, we will get [expletive] torn apart in 2022,” said Representative Spanberger.

Progressives have pushed back. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York said this week that some of the members who lost had made themselves “sitting ducks” by ignoring social media ads and other modern methods of campaigning.

Professor Cain of Stanford University says this tension is reflective of another trend revealed in the election returns.

“Both of the political parties are struggling with their core activist, heavily ideological bases,” he says.

This also reflects the polarization of American politics, he says. Party sorting, with conservative Democrats turning Republican and moderate Republicans turning Democratic, has in recent decades removed factions that used to keep both parties from becoming more extreme.

“The question now is ... how do we govern with that kind of polarization within the electorate?” he says.

Juliet Hooker, a professor of political science at Brown University, says she does not see the election results as a repudiation of progressives. Mr. Biden won with the enthusiastic support of a lot of people on the left, she says, who set aside their personal beliefs to unite behind their party’s candidate.

“The reality is that Democrats can’t win without progressives,” she says.

GOP’s demographic destiny

For some years, top Republicans have worried about the demographic destiny of their party. It has become whiter and older, as the Democratic Party has become more diverse and younger. And white voters are shrinking as a percentage of the U.S. electorate, while Black and Hispanic voters and other people of color are increasing. The GOP may be on track to shrink so much that at some point in the future it simply becomes uncompetitive on a national level.

On one level, the 2020 vote may already reflect this. President Trump received over 71 million votes, the most ever cast for an incumbent – but President-elect Biden got about 76 million votes, the most a presidential candidate has ever received, period.

There are millions more votes still to be counted in heavily blue states such as New York and California. Mr. Biden’s overall lead is certain to grow.

But one surprise result may be good news for the GOP as it confronts its demographic limits. President Trump increased his share of the Hispanic vote, from about 28% four years ago to about 32% now. Meanwhile, his share of the Black vote also increased, albeit from very low levels to begin with. President Trump won 20% of Black men, for instance. (His support among Black women was about 9%.)

That’s led Dave Wasserman, House editor of the Cook Political Report, to conclude that it is now harder to argue that the GOP coalition is demographically “dying out.”

“As with past waves of immigrants throughout U.S. history, Hispanic voters are beginning to vote a little closer to the rest of the country – and it’s one possible path forward,” Mr. Wasserman tweeted on Nov. 9.

The Hispanic community itself is diverse, with origins rooted in different nations, and opinions varied and dependent on factors such as income, where they live, and religious affiliation. Democrats should not look at them as a monolithic bloc that cares primarily about immigration, say experts.

“You have to cover Latinos depending on where they are,” says Chris Zepeda-Millán, an associate professor in UCLA’s public policy department.

This year, the Trump campaign did a better job of turning out conservative-leaning Cuban Americans in Florida, through ad “micro-targeting” and other means, says Professor Zepeda-Millán. That helped push President Trump to victory in the key state.

Meanwhile, Mr. Biden’s outreach was targeted more to Mexican Americans and Hispanics of Central American origin, which helped him in some of his key state wins.

“[Latino voters] could potentially be making the difference in Pennsylvania, Wisconsin – places that we don’t think about the Latino vote,” says Professor Zepeda-Millán.