Why couldn't Rep. Bobby Rush wear hoodie on House floor?

Loading...

| Washington

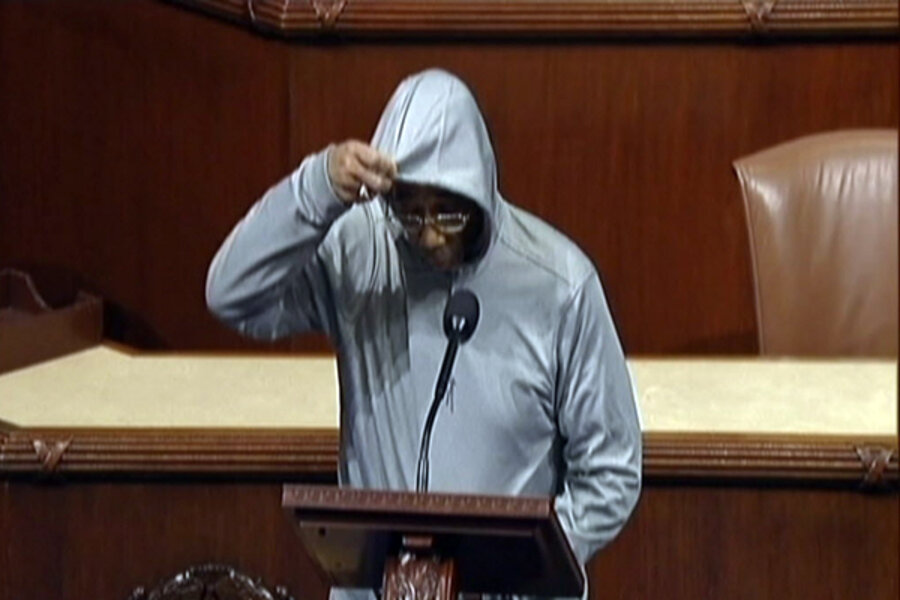

Hoodies on the House floor are verboten, apparently. Rep. Bobby Rush (D) of Illinois was scolded and escorted from the chamber of the House of Representatives on Wednesday morning, when he attempted to give a speech on the need for a full investigation of the Trayvon Martin shooting while wearing sunglasses and a gray hooded sweat shirt.

“Racial profiling has to stop, Mr. Speaker,” said Representative Rush while doffing his suit jacket to reveal his hoodie garb. “Just because someone wears a hoodie does not make them a hoodlum.”

Rush continued to speak while the presiding officer, Rep. Gregg Harper (R) of Mississippi, banged the gavel, ordering him to desist. Eventually someone from the office of the House sergeant-at-arms appeared and escorted Rush, hoodie and all, off the floor.

The reason for the uproar is that Congress has a dress code. Men are expected to wear coats and ties, and women to wear correspondingly serious clothing. Under House Rule XVII, Section 5, hats are prohibited, and a hoodie is unquestionably a head covering.

“The Sergeant-at-Arms is charged with the strict enforcement of this clause,” concludes that section.

Senior Democrats played down the kerfuffle. Minority leader Nancy Pelosi noted that when she first came to Congress, women were prohibited from wearing pants on the floor. But really, why should the House be such a stickler on items of dress? In the 1830s and 1840s – admittedly, a much more heated era in US history – many lawmakers carried weapons, and violence was not uncommon. In some Asian legislatures today, debates can end in fistfights.

The reason for the rules on decorum may be that civility stands on a slippery slope.

“As [humorist] Will Rogers observed, members call themselves gentlemen and gentlewomen, because the alternatives would be to call one another polecats and coyotes, or worse, liars, hypocrites, stupid, dumb, demagogues, socialists, communists, none of which lend themselves to the deliberative process so important to the governance of the nation,” wrote Ray Smock, director of the Robert C. Byrd Center for Legislative Studies at Shepherd University in Shepherdstown, W.Va., last October.

Mr. Smock, who served as historian of the House from 1983 to 1995, believes that civility now “is at one of the lowest ebbs in congressional history.”

Such breaches of decorum as the “You lie!” shout of Rep. Joe Wilson (R) of South Carolina during President Obama’s 2009 speech to Congress on health-care reforms may be indicative of a larger, paralyzing incivility based on bitter partisanship, in Smock’s view.

Narrower measures indicate that Congress may be becoming more civil, not less. An Annenberg Public Policy Center study of the number of times lawmakers are reprimanded for out-of-bounds language by having their words “taken down” found that infractions have become relatively few and farther between.

“Overall, civility, not incivility, is the norm in the House,” said the September 2011 report.

All that said, Rush had particular incentive to speak out on the Trayvon Martin issue. A former member of the 1960s Black Panthers, Rush was active in the civil rights movement of the era. His own 29-year-old son died of a gunshot.