Little girls or little women? The Disney princess effect

Loading...

| Boston

A few years ago, Mary Finucane started noticing changes in the way her 3-year-old daughter played. The toddler had stopped running and jumping, and insisted on wearing only dresses. She sat on the front step quietly – waiting, she said, for her prince. She seemed less imaginative, less spunky, less interested in the world.

Ms. Finucane believes the shift began when Caoimhe (pronounced Keeva) discovered the Disney Princesses, that omnipresent, pastel packaged franchise of slender-waisted fairy-tale heroines. When Finucane mentioned her suspicions to other parents, they mostly shrugged.

"Everyone seemed to think it was inevitable," Finucane says. "You know, it was Disney Princesses from [ages] 2 to 5, then Hannah Montana, then 'High School Musical.' I thought it was so strange that these were the new trajectories of female childhood."

She decided to research the princess phenomenon, and what she found worried her. She came to believe that the $4 billion Disney Princess empire was the first step down a path to scarier challenges, from self-objectification to cyberbullying to unhealthy body images. Finucane, who has a background in play therapy, started a blog – "Disney Princess Recovery: Bringing Sexy Back for a Full Refund" – to chronicle her efforts to break the grip of Cinderella, Belle, Ariel, et al. on her household.

Within months she had thousands of followers.

"It was validating, in a sense, that a lot of parents were experiencing it," she says. "It was this big force entering our lives so early, with such strength. It concerned me for what was down the road."

Finucane's theory about Disney Princesses is by no means universal. Many parents and commentators defend Happily Ever After against what some critics call a rising "feminist attack," and credit the comely ladies with teaching values such as kindness, reading, love of animals, and perseverance.

If there's any doubt of the controversy surrounding the subject, journalist Peggy Orenstein mined a whole book ("Cinderella Ate My Daughter") out of the firestorm she sparked in 2006 with a New York Times essay ("What's Wrong With Cinderella?").

Disney, for its part, repeated to the Monitor its standard statement on the topic: "For 75 years, millions of little girls and their parents around the world have adored and embraced the diverse characters and rich stories featuring our Disney princesses.... [L]ittle girls experience the fantasy and imagination provided by these stories as a normal part of their childhood development."

And yet, the Finucane and Orenstein critique does resonate with many familiar with modern American girlhood as "hot" replaces pretty in pink, and getting the prince takes on a more ominous tone. Parents and educators regularly tell re-searchers that they are unable to control the growing onslaught of social messages shaping their daughters and students.

"Parents are having a really hard time dealing with it," says Diane Levin, an early childhood specialist at Wheelock College in Boston who recently co-wrote the book "So Sexy So Soon." "They say that things they used to do aren't working; they say they're losing control of what happens to their girls at younger and younger ages."

It only takes a glance at some recent studies to understand why parents are uneasy:

•A University of Central Florida poll found that 50 percent of 3-to-6-year-old girls worry that they are fat.

•One-quarter of 14-to-17-year-olds of both sexes polled by The Associated Press and MTV in 2009 reported either sending naked pictures of themselves or receiving naked pictures of someone else.

•The marketing group NPD Fashionworld reported in 2003 that more than $1.6 million is spent annually on thong underwear for 7-to-12-year-olds.

•Children often come across Internet pornography unintentionally: University of New Hampshire researchers found in 2005 that one-third of Internet users ages 10 to 17 were exposed to unwanted sexual material, and a London School of Economics study in 2004 found that 60 percent of children who use the Internet regularly come into contact with pornography.

And on, and on. It's enough, really, to alarm the most relaxed parent.

But as Professor Levin, Finucane, and Orenstein show, there is another trend today, too – one that gets far less press, but is much more hopeful.

Trying to make a safer, healthier environment for girls, an ever-stronger group of educators, parents, institutions, and girls themselves are pushing back against growing marketing pressure, new cyberchallenges, and sexualization, which the American Psychological Association (APA) defines in part as the inappropriate imposition of sexuality on children.

Many are trying to intervene when girls are younger, like Finucane, who doesn't advocate banning the princesses but taking on the ways that they narrow girls' play (advocating more color choices, suggesting alternative story plotlines). Some tap into the insight and abilities of older girls – with mentoring, for example. Still others take their concerns into the public sphere, lobbying politicians and executives for systemic change such as restricting sexualized advertising targeting girls.

Together, they offer some insights for how, as Finucane says, to bring sexy back for a refund.

Soccer heading makes a bad hair day

The first step, some say, is to understand why any of this matters.

By many measures, girls are not doing badly. According to the Washington-based Center on Education Policy, high school girls perform as well as boys on math and science tests and do better than their male peers in reading. Three women now graduate from college for every 2 men. Far more women play sports, which is linked to better body image, lower teen pregnancy rates, and higher scholastic performance.

And opportunities for girls today are much broader than 50 years ago when, for example, schools didn't even allow girls to wear pants or to raise and lower the flag, notes Stephanie Coontz, co-chair of the nonprofit Council on Contemporary Families. "It is important to keep all of this in perspective," she says.

Still, there are signs of erosion of the progress in gender equity. Take athletics.

"Girls are participating in sports at a much increased level in grade school," says Sharon Lamb, a professor of education and mental health at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. But, she adds, they start to drop out of sports at the middle school level when they start to believe that sports are unfeminine and unsexy.

The Women's Sports Foundation found that 6 girls drop out of sports for every 1 boy by the end of high school, and a recent Girl Scout study found that 23 percent of girls between the ages of 11 and 17 do not play sports because they do not think their bodies look good doing so.

And looking good, Ms. Lamb says, is increasingly tied to what it means to play. Star female athletes regularly pose naked or seminaked for men's magazines; girls see cheerleaders (with increasingly sexualized routines) on TV far more than they see female basketball players or other athletes.

The effects are felt in academia as well. Earlier this year, a Princeton University study found a growing leadership gap among male and female undergraduates. Nannerl Keohane, who chaired the Princeton steering committee, wrote in an e-mail interview that "the climate was different in the late 1990s and the past decade." And she linked the findings to shifts in popular culture such as "the receding of second-wave feminist excitement and commitment, a backlash in some quarters, a re-orientation of young women's expectations based on what they had seen of their mothers' generation, a profound reorientation of popular culture which now glorifies sexy babes consistently, rather than sometimes showing an accomplished woman without foregrounding her sexuality."

This "sexy babes" trend is a big one.

"For young women, what has replaced the feminine mystique is the hottie mystique," Ms. Coontz says. "Girls no longer feel that there is anything they must not do or cannot do because they're female, but they hold increasingly strong beliefs that if you are going to attempt these other things, you need to look and be sexually hot."

In television shows, for instance, women are represented in far more diverse roles – they are lawyers, doctors, politicians. But they are always sexy. A woman might run for high political office, but there is almost always analysis about whether she is sexy, too.

In 2010, the APA released a report on the sexualization of girls, which it described as portraying a girl's value as coming primarily from her sexual appeal. It found increased sexualization in magazines, by marketers, in music lyrics, and on television – a phenomenon that includes "harm to the sexualized individuals themselves, to their interpersonal relationships, and to society."

Sexualization, it reported, leads to lower cognitive performance and greater body dissatisfaction. One study cited by the report, for instance, compared the ability of college-age women to solve math problems while trying on a sweater (alone in a dressing room) with that of those trying on swimsuits. Sweater wearers far outperformed the scantily dressed.

Research also connects sexualization to eating disorders, depression, and physical health problems. Even those young women – and experts say there are growing numbers of them – who claim that it is empowering to be a sex object often suffer the ill effects of sexualization.

"The sexualization of girls may not only reflect sexist attitudes, a society tolerant of sexual violence, and the exploitation of girls and women but may also contribute to these phenomena," the APA said.

Objectifying women is not new, of course.

"What's different is just the sheer amount of messaging that girls are getting, and the effective way that these images are used to market to younger and younger girls," says Lyn Mikel Brown, an education professor at Colby College in Waterville, Maine. "They're getting it relentlessly. And in this busy world it's somehow harder for parents to stop and question it. It's like fish in water – it's the water. It's in the air. It's easy for it to get by us."

Help girls to see the problem

So what to do? To start, girls can become media critics, says Professor Brown's high school-age daughter, Maya Brown. The younger Brown serves on the Girls' Advisory Board of Hardy Girls Healthy Women, an organization based in Maine that develops girl-friendly school curricula and runs a variety of programs for girls.

"There are so many images of girls, and they are always objectifying – it's hard to make that go away," Maya says. "What you really need is for the girls to be able to see it."

She knows this firsthand. Her mother would regularly pause television shows or movies to talk about female stereotypes; when she read to Maya, she would often change the plotlines to make the female characters more important. (It was only when Maya got older that she realized that Harry Potter was far more active than Hermione.)

"It would get kind of annoying," Maya, now 16, says with a laugh. "When we were watching a movie and she'd pause it and say, 'You know, this isn't a good representation,' I'd be like, 'Yeah, yeah, yeah, I caught that. Can we watch our show now?' "

Professor Brown had many opportunities to intervene. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, the percentage of television shows with sexual content – from characters talking about their sexual exploits to actual intercourse – increased from 54 percent in 1998 to 70 percent in 2005.

In her book, Levin says that the numbers would be even higher if advertisements were included. And reality television, which has ballooned during the past decade, is particularly sexualizing. Scholars point out that the most popular reality shows either have harem-style plots, with many women competing to please one man, or physical-improvement goals.

Young girls get similarly sexualizing messages in their own movies and television shows. The Geena Davis Institute on Gender and Media found recently that fewer than 1 in 3 speaking characters (animal or human) in G-rated family films are female, and even animated female characters tend to wear sexualized attire: Disney's Jasmine, for instance, has a sultry off-the-shoulder look, while even Miss Piggy shows cleavage.

Co-opting the images

Given this backdrop, many child development experts say the best way to handle the media onslaught for younger girls is for parents to simply opt out.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends no screen time – television, movies, and Internet – for infants under 2 years of age; for older children, the AAP suggests only one to two hours a day. This would be a significant change for most American families. In 2003, the Kaiser Family Foundation found that 36 percent of children under 6 live in a house where the TV is on all or almost all of the time; 43 percent of children ages 4 to 6 have a TV in their bedroom. In 2010 the foundation reported that, on average, children ages 8 to 18 consume 10 hours, 45 minutes' worth of screen media content a day.

Even if parents limited TV and movies, though, the sexualization of women would still get through on the radio, in magazines at grocery store checkout lines, on billboards, and in schools, not to mention on the all-powerful Internet. Those images, as in television, have become far more sexualized.

In one recent study, University of Buffalo sociologists Erin Hatton and Mary Nell Trautne examined the covers of Rolling Stone magazine between 1967 and 2009. They found a "dramatic increase in hypersexualized images of women," to the point that by 2009, nearly every woman to grace the magazine's cover was conveyed in a blatantly sexual way, as compared with 17 percent of the men. (Examples include a tousled-haired Jennifer Aniston lying naked on a bed, or a topless Janet Jackson with an unseen man's hands covering her breasts.)

With no way to get away from the sexualized images, Maya says, it's better to recognize and co-opt them.

She and other young women helped develop the website poweredbygirl.org on which girls blog, comment, and share ideas about female sexualization in the media. The site includes an app that lets users graffiti advertisements and then post the altered images – one recent post, for instance, takes a Zappos magazine advertisement showing a naked woman covered only by the caption "more than shoes!" and adds, "Yet no creativity" to the slogan.

"Once it's brought to light in a satirical way, it loses its power," says Jackie Dupont, the programs director at Hardy Girls Healthy Women. "The ridiculousness about what the advertisements are trying to say about women becomes more apparent."

Sexy's not about sex, it's about shopping

Media images, though, are only a part of the sexualization problem. More invasive, Levin and others say, is marketing.

Since the deregulation movement of the 1980s, the federal government has lost most oversight of advertising to children. This has encouraged marketers to become increasingly brazen, says Levin. Marketers are motivated to use the sexualization of women to attract little girls, or violence to attract little boys, because developmentally children are drawn to things they don't understand, or find unnerving, Levin says.

In this context, she says, sexy is not about sex, but about shopping. If girls can be convinced to equate "sexy" with popularity and girlness itself, and if "sexy" requires the right clothes, makeup, hairdo, accessories, and shoes, then marketers have a new bunch of consumers.

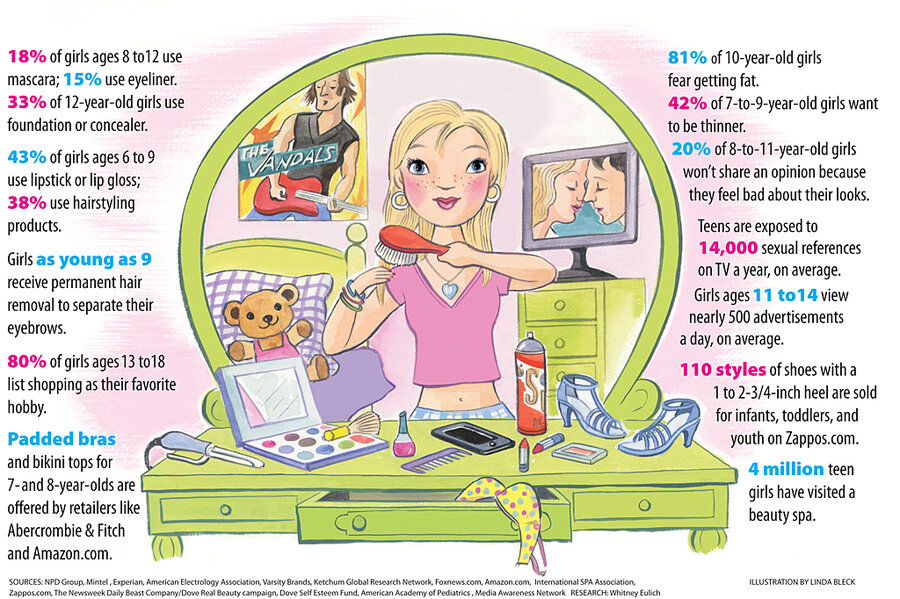

"Age compression," the phenomenon of younger children adopting patterns once reserved for older youths, helps with sales. If girls start wearing lip gloss when they are 6 years old (as almost half of them do, according to Experian Simmons national consumer research) and mascara when they are 8 (the percentage of 8-to-12-year-olds wearing mascara doubled between 2007 and 2009, to almost 1 in 5, according to market research from the NPD Group), then it's clearly better for cosmetic companies. This is also why, Levin speculates, thong underwear is now sold to 7-year-olds, and padded bras show up on the racks for 5-year-olds.

Meanwhile, there are deepening gender divisions in toys, clothing, and play activities. Orenstein explores in "Cinderella Ate My Daughter" how the color pink has become increasingly ubiquitous to the point where many young girls police each other with a pink radar – if that tricycle, for instance, isn't pink, well then, you shouldn't be riding it.

Brown points out in her book that there is no pink equivalent for boys. Although the color blue, sports equipment, and fire engines grace much of their décor, boys still have far more options of how to define themselves.

"In unprecedented levels, girls are being presented with a very narrow image of girlhood," Brown says.

One of the best ways to keep girls from falling into rigid gender roles is to broaden their horizons.

"If we are bombarded with thousands of images a day that give the illusion of choice, but are in fact really simplistic and repetitive, it's important to not just say girls can do anything, but to give them the actual experience," said Ms. Dupont from Hardy Girls Healthy Women, where the Adventure Girls program for second- to sixth-graders connects girls with women who have excelled in nontraditional fields, from construction and rugby to chemistry and dog-sledding.

This is what Finucane tried to do with her daughter. She did not want to crush Caoimhe's fantasies, but she also wanted her to see more of the possibilities open to girls. So although Caoimhe wanted to read only Disney Princess books – titles such as "Cinderella: My Perfect Wedding" – Finucane insisted on sharing stories about Amelia Earhart and other powerful women. She bought native American dress-up clothes and a Princess Presto outfit to go with the frothy pink Disney gowns.

Trying to stay one step ahead

Finucane says that Caoimhe, now 5, is pretty much free of the princess obsession. These days she is entranced by "James and the Giant Peach" and "The Wizard of Oz."

"I try to stay maybe one step ahead," Finucane says. "The grip they had is lost. She's still into characters and theatrical production, but she no longer believes that you can't leap if you're a princess, or female."

Parents' involvement is key, Levin says, but they do not have to act alone. Over the past few years, a growing group of advocacy organizations have formed to help fight against marketing pressure and sexualization.

Levin and others have campaigned for new regulations on how advertisers can approach children; groups such as truechild.org and Campaign for a Commercial Free Childhood have also pushed for marketing restrictions and have held summits about countering the consumer culture and sexualization. The organization TRUCE – Teachers Resisting Unhealthy Children's Entertainment – publishes media and play guides in which they review toys, check marketers' claims, and recommend age-appropriate activities. Recently, actress Geena Davis joined Sen. Kay Hagan (D) of North Carolina and Rep. Tammy Baldwin (D) of Wisconsin to lobby for a bill that would support efforts to improve the image of women and girls in the media.

Girls themselves have joined different advocacy efforts, including organizing and participating in the SPARK (Sexualization Protest: Action, Resistance, Knowledge) Summit in New York City, a gathering of girls and adults who hold forums on media awareness, sexuality, and fighting stereotypes.

Schools can also share the burden. Catherine Steiner-Adair, a therapist and educational consultant, has worked with school systems across the country for 30 years to develop curriculum that will increase social and emotional intelligence among boys and girls. She says that programs where girls are encouraged to create and then delve into their own projects are often successful.

"Girls discover what it means to take their own interests seriously and to pursue them deeply and vigorously," she says.

She says that schools that can start focusing on these issues earliest have the best success. In a four-year study published in 2007 by the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, researchers found that students who participate in these sorts of programs show more empathy, self-confidence, and more academic success than their peers without social-emotional curriculum.

"Given today's culture and the access people have and the lack of boundaries between home and school and between people and technology, you have to begin this work in first grade," she says. "The schools that are doing it in first grade are very different cultures – they're kinder, they're more respectful, they're less bullying."

Girls stuck in the social-feedback loop

Ms. Steiner-Adair's point about technology is the elephant in the chat room.

In any conversation about the sexualization of girls, the Internet is always mentioned as a huge new challenge. Not only does the Web allow easy – and often unwanted – access to sexual images (in terms of numbers of websites and views, porn is king of the Web), it offers a social-feedback loop that is heavy on appearance and superficiality, and low on values that scholars say might undermine sexualization, such as intelligence and compassion.

Girls – and boys – encourage each other to embrace sexualization. Teens who post sexy pictures of themselves on Facebook, for instance, are rewarded with encouraging comments. Educator and author Rachel Simmons, who recently rereleased "Odd Girl Out," her book about girl aggression, with new chapters on the Internet, tells of a 13-year-old who posted a photo of herself in tight leggings, her behind lifted toward the camera.

"She posts it on Facebook and gets 10 comments underneath it telling her how great her butt looks," Ms. Simmons says.

"Girls are using social media to get feedback in areas that they've been told by the culture that they need to express or work on. That's not girls being stupid.... Many girls post or send provocative images because they're growing up in a culture that places a lot of value in their sexuality."

The answer is not for parents to cancel the Wi-Fi, Simmons and others say. There are many ways that girls can use the Internet and social media for good. But the technology does require monitoring – and self-evaluation.

It's hard to criticize a girl for delving into social media, for instance, when her parents are constantly checking their own iPhones.

"We can't sit there and say, 'Oh, the kids are so messed up,' " she says. "We have to look at ourselves."