How Indigenous people’s work can save aquatic grass and terrestrial forest

Loading...

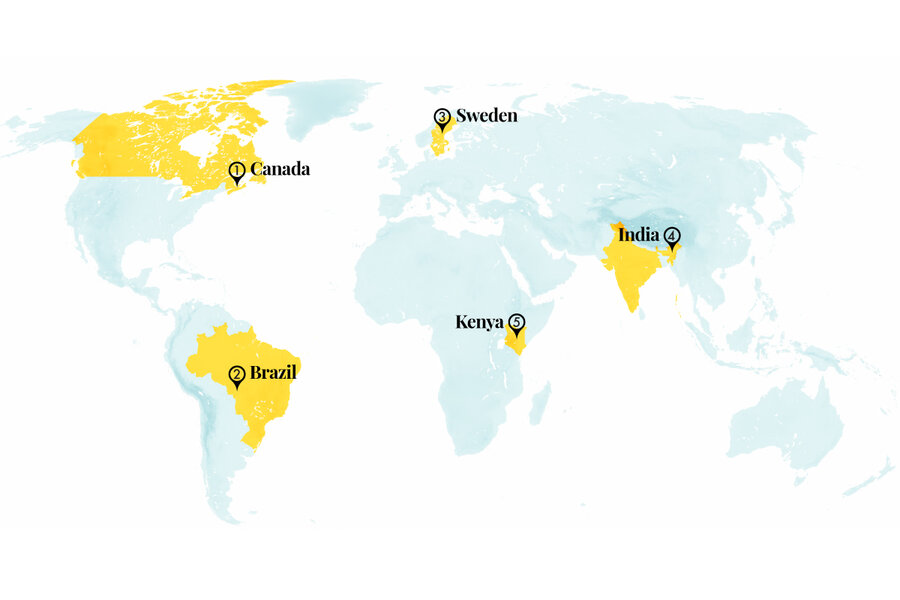

1. Canada

Scientists and Indigenous knowledge holders are teaming up to save Canada’s eelgrass by using “two-eyed seeing,” an approach that honors the insights and skills of both communities.

As eelgrass meadows struggle to cope with seabed disturbance, pollution, warming water, and invasive species, Dalhousie University researchers and the First Nations of Nova Scotia are working together in the lab and the field to study eelgrasses, keystone species of some of the ocean’s most biodiverse ecosystems.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onOur progress roundup highlights several advancements that put plants to work – feeding people, keeping forests diverse, and even recycling batteries.

In the waters of Maliko’mijk (Mergomish Island), sacred to the members of the Pictou Landing First Nation, volunteers and scientists transplanted eelgrass to restore vital habitat for the American eel, a cultural and nutritional staple of the Indigenous Micmac communities in Nova Scotia. Researchers are also exposing eelgrass seed to different salinity and temperature levels while examining genetic differences. Such work allows them to predict which types of grass will be most resilient to climate change, helping to guide decisions on the best strains to replant.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and industry players are interested in the eelgrass studies for the potential impact on carbon credit markets and to increase knowledge of the meadows’ carbon storage properties.

Source: Mongabay

2. Brazil

Women are collecting seeds and building networks to help restore Brazil’s forests. The world’s most biodiverse country, Brazil seeks to reforest 31 million acres by 2030. Seed collection is crucial to reaching this goal. The country is currently without a government-led forest restoration program, and grassroots groups are finding ad hoc ways to collaborate and exchange knowledge.

In July, members of the Reseba network, founded by six Indigenous groups in the state of Rondônia, traveled to neighboring Mato Grosso to learn from Brazil’s oldest seed collectors association. The Xingu Seeds Network, which has more than 550 members, has collected seeds from some 200 species. Members discussed the importance of storing seeds free of fungi and pests, and showed how driving a car over the seeds of the jatobá-do-cerrado tree can help to break them up.

Seed collectors face various challenges, including changes in public policy that allow landowners to delay land restoration efforts. An estimated 49.4 million acres of such land are eligible, according to the Forest Code Observatory, a network of civil society groups. Its purpose is to help strengthen implementation of the Brazilian law that protects native vegetation on private land but has always been difficult to enforce.

While they await the government’s reestablished commission to oversee restoration, the collector networks are working to enhance women’s income and autonomy.

Source: Mongabay, Partnerships for Forests

3. Sweden

Scientists discovered a process for more efficient battery recycling. Lithium-ion batteries power everything from phones to electric vehicles, but the race to electrify transportation has increased the demand for the minerals necessary to make these batteries. Researchers from Chalmers University of Technology found that by using oxalic acid, the strongest of the natural plant acids, they could recover through hydrometallurgy 100% of a battery’s aluminum and 98% of its lithium, and minimize the loss of other valuable heavy metals. An estimated 256 recycled batteries or 250 tons of ore are needed to produce 1 ton of lithium.

In traditional hydrometallurgy, a battery’s metals are reduced to a black powder and dissolved in an inorganic acid. Metals are separated in a multistep process. In the new method, lithium and aluminum are removed first, reducing the waste occurring from each step. By fine-tuning temperature, concentration, and time, the researchers have found “an innovative method that can offer the recycling industry new alternatives,” said Martina Petranikova, research lead.

Source: Chalmers University of Technology, Separation and Purification Technology

4. India

Solar-powered boat clinics are bringing health care to river communities in India’s state of Assam. About 2.5 million people live on the 2,500 nonurbanized islands of the Brahmaputra River, which flows through almost the entire east-west width of the state. Since 2005, floating clinics equipped with an array of health care infrastructure have provided the isolated, flood-prone communities with free medical care. And since 2017, solar power has raised the level of care and improved working conditions for the professionals who live on the boats.

Run by a partnership between the government and the nonprofit Centre for North East Studies and Policy Research, each clinic hosts 12 to 15 patients at once, providing a range of services from prenatal care to malaria checkups. Solar power has allowed medical personnel to ditch noisy, polluting diesel generators. Round-the-clock electricity refrigerates medicines and enables fewer supply trips to the mainland. Residents say they save time and money by not having to travel for care, and the research center says 18,000 to 20,000 people use the clinics every month.

Source: Reasons to be Cheerful

5. Kenya

Scholarships for nursing students have placed skilled professionals in remote areas, bridging critical health care gaps. Over the past seven years, Kenya’s partnership with the World Bank has supported the education of 1,200 nurses from communities with low indicators of maternal and child health. Many of these students were from disadvantaged minority groups, who had felt that training was out of reach.

The government currently employs nearly 600 nurses in health care facilities with a dearth of skilled medical professionals. The initiative selects nurses native to each region to facilitate communication in the local language and ensure that services are best suited for the populations living there, which also builds trust between communities and health care professionals. The program places a special emphasis on midwifery and emergency pregnancy care, often enabling patients to remain close to home instead of be transferred to a distant hospital.

Kenya has seen an uptick in some of its health metrics in the last two decades, with mortality rates for children under age 5 falling by half. The program next seeks to expand into more communities, and calls for more investment in infrastructure and medical equipment.

Source: World Bank Blogs