Mark Twain's turkey tale – perhaps the funniest in American literature

Loading...

In December of 1906, with memories of Thanksgiving no doubt fresh in his mind, Mark Twain recorded the story of how, many years before, he had tried to capture a turkey and failed.

That’s how Twain ended up crafting perhaps the funniest turkey tale in American literature, a yarn worth remembering as another Thanksgiving arrives.

In 1906, just four years before his death, Twain began to focus more closely on dictating reminiscences for his autobiography. He decided to publish some fragments of his work-in-progress in North American Review, and also allowed Harper’s to print an excerpt, “Hunting the Deceitful Turkey.”

Drawn from Twain’s boyhood in Hannibal, Missouri, it recounts a long day hunting with his uncle and cousins. Squirrels and turkeys were the game of choice. Twain, though armed with a small shotgun, decided, as a point of honor, to take his big bird alive.

How hard could it be? The mother turkey he’d spotted was obviously lame, an easy enough quarry for a wiry boy with boundless energy.

What Twain eventually learned, after an interminable time on the trail, is that turkeys have a genius for feigning injury – a clever ploy to throw off predators.

“I often got within rushing distance of her, and then made my rush,” he recalled, “but always, just as I made my final plunge and put my hand down where her back had been, it wasn’t there; it was only two or three inches from there and I brushed the tail-feathers as I landed on my stomach – a very close call, but still not quite close enough; that is, not close enough for success, but just close enough to convince me that I could do it next time.”

In fruitlessly pursuing his prize, the young Twain – his given name, of course, was Samuel Clemens – got lost in the woods. “I found a deserted log cabin and had one of the best meals there that in my life-days I have eaten,” Twain told readers. “The weed-grown garden was full of ripe tomatoes, and I ate them ravenously, though I had never liked them before.”

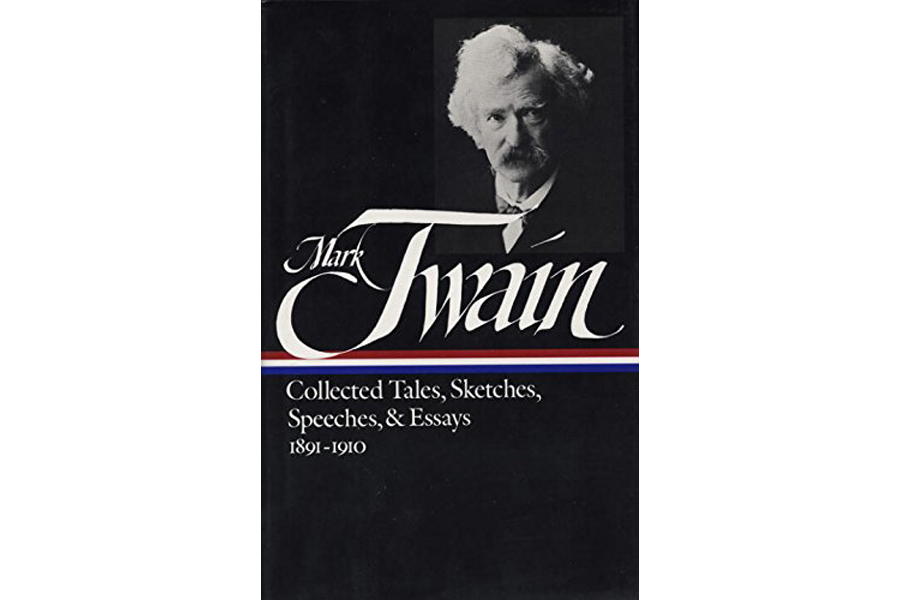

“Hunting the Deceitful Turkey” is included in “Mark Twain: Collected Tales, Sketches, Speeches and Essays, 1891-1910,” published by the Library of America. Each week, the Library of America emails fans a story from a book in its collection, and “Hunting the Deceitful Turkey” ranks among the 10 most popular selections that LOA has ever featured in its “Story of the Week” mailer.

Twain fans can read Twain’s turkey tale in full here, where you can also get information on how to subscribe to LOA’s free “Story of the Week” service.

Twain cautioned against trying too hard to find a moral in his work, but his hunting tale conveys an obvious lesson. If you want a turkey for your holiday table, it’s probably best to go to the grocery store.