Did Neanderthals create Europe's first cave paintings?

Loading...

A series of cave paintings in Spain are thousands of years older than scientists realized, raising speculation — but no proof — that Neanderthals could have been the earliest wall artists in Europe.

The oldest image, a large red disk on the wall of El Castillo cave in northern Spain, is more than 40,800 years old, according to an advanced method that uses natural deposits on the surfaces of the paintings to date their creation. The new findings, detailed in the June 15 issue of the journal Science, make the paintings the oldest reliably dated wall paintings ever.

They also push the art back into a time when early modern humans, who looked anatomically like us, co-existed with their Neanderthal cousins in Europe. Some researchers think the paintings may predate European Homo sapiens, suggesting that the art may not be the work of modern humans at all.

"It would not be surprising if the Neanderthals were indeed Europe's first cave artists," said study researcher Joao Zilhao, a professor at the Institució Catalana de Recerca i Estudis Avançats (ICREA) at the University of Barcelona. [See Photos of the Ancient Cave Art]

Our cultured ancestors

Neanderthals have been portrayed as brutish, animalistic cavemen, but the archaeological evidence suggests they weren't dummies. They buried their dead, made complex tools, and used decorative pigments. In 2010, Zilhao and his colleagues excavated shells coated in red and yellow pigments from a Neanderthal site in southern Spain. They suspect the pigments were used as makeup or body paint.

Neanderthals went extinct around 30,000 years ago. Before they did, they mixed and mingled with humans. Between 1 percent and 4 percent of some modern humans' DNA came from Neanderthals, indicating the two species got amorous.

Modern humans arrived on the European scene between about 41,000 and 42,000 years ago. Some of the earliest archaeological evidence of their existence shows them to be a sophisticated bunch, too. At one site in Germany with the particularly early date of between 42,000 to 43,000 years ago, archaeologists recently unearthed flutes made of bird bones and mammoth ivory, the oldest musical instruments in Europe. [10 Mysteries of the First Humans]

But the age of cave paintings has been tougher for archaeologists to pin down. Their usual method of radiocarbon dating requires organic material, and most mineral pigments contain none. With very old samples, radiocarbon dating is also prone to contamination.

A new look at old art

Zilhao and his colleagues turned to a different method: uranium-thorium dating. As anyone who has seen a stalactite knows, caves are always undergoing slow change. The same processes that create stalactites and stalagmites leave thin deposits of the mineral calcite over some cave paintings. This calcite contains miniscule amounts of radioactive uranium, which decays to thorium over time.

The researches painstakingly scraped these natural calcite deposits off the top of the paintings, stopping just before they reached the pigment. Then, using a device called a mass spectrometer, they took rice-grain-size samples of this calcite and counted the uranium and thorium atoms. The ratio between the two determines the date of the calcite formation, since the decay happens at a known rate.

Because the calcite came after the paintings, this sets a minimum age for the art. What researchers don't know is how long the initial calcite deposit took, so the paintings could be anywhere from hundreds to thousands of years older than the minimum dates.

The researchers took samples from 11 Spanish caves, including famed spots like Altamira with its painted herds of bison. At Altamira, they found an image of a red horse that dates back at least 22,000 years and a clublike image that is at least 35,600 years old. The club symbol has been painted over with the famous colorful bison herd, which dates to around 18,000 years ago. In other words, Altamira was a popular spot for artists for a very long time. [Images: Altamira & Other Amazing Caves]

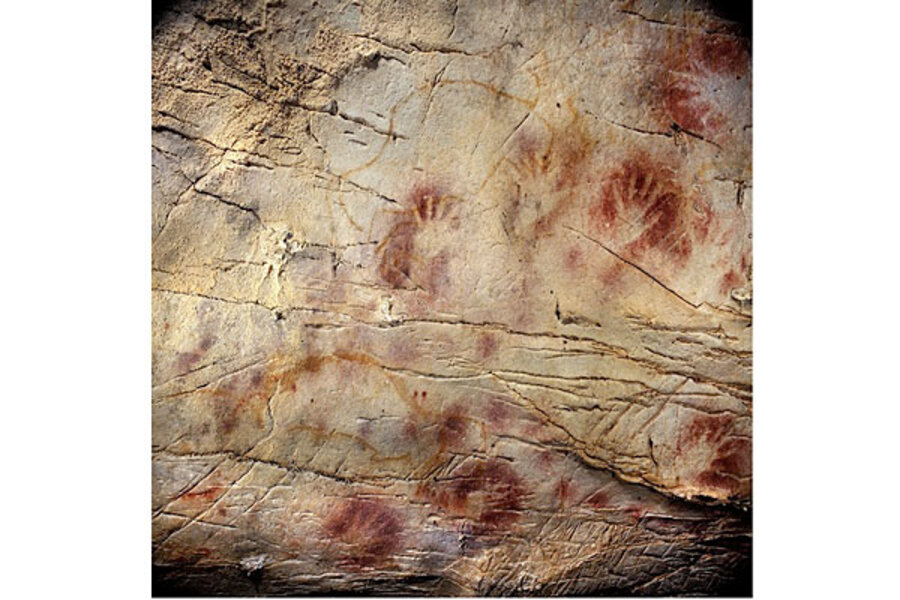

At another cave, El Castillo in northern Spain, the researchers found primitive art of mind-boggling age. This cave contained the 40,800-year-old red disk. It also sported a hand stencil, created by an artist spitting red pigment over his or her hand to leave a handprint, that dates back more than 37,300 years.

"We simply did not have any dates this old before," Zilhao said. "Even if this is made by modern humans, we are pushing the age of this stuff by 5,000 years."

The previous oldest-known rock art in Europe was not a painting, but etchings of likely female genitalia symbols made about 37,000 years ago in France.

Human or Neanderthal?

But whose handprints are on the decorated cave walls? According to Zilhao, a minimum date of about 40,800 years ago for the calcite over the red disk suggests a painting that is even older.

"It is enough that the motif is painted just a few hundred years, just a thousand years, before this minimum age to place it in a time period where there were no modern humans in Europe," he said.

Paul Bahn, a British archaeologist not involved in the study, agreed that the dates are convincing.

"Certainly for the El Castillo dates, I think there is no question at all," Bahn told LiveScience. "It has to be Neanderthals."

Other researchers aren't as sure. The cave art falls into an era of overlap between humans and Neanderthals in Europe, said Chris Stringer, the research leader in human origins at the Natural History Museum in London. Early modern human fossils and artifacts have been found in Britain as early as 41,000 years ago, and at the German musical instrument site as much as 43,000 years ago, Stringer, who wasn't involved in the current study, told LiveScience. That means the cave art isn't necessarily from a pre-human era.

"Modern humans are still the most likely candidates for this," he said.

The uranium-thorium dating method that sparked this debate is likely the method that will settle it. The team sampled only a tiny percentage of cave paintings, said study leader Alistair Pike, an archaeologist at the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom. There are many more caves awaiting accurate dating.

"I think it's fairly a straightforward thing to prove if they were painted by Neanderthals," Pike said. "All we have to do is go back and date more of these samples and find a date that predates the arrival of modern humans in Europe."

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

- Image Gallery: Our Closest Human Ancestor

- Gallery: Europe's Oldest Rock Art

- Top 10 Things that Make Humans Special

Copyright 2012 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.