Can US and Taliban cut a deal in Afghanistan?

Loading...

| Kabul, Afghanistan; and Islamabad, Pakistan

Muhammad Hassan Haqyar once sat close to the heart of Afghan power, wielding influence as an administrator in the Ministry of Mines during the Taliban years. The government in those days was filled with illiterate bumpkins better versed in an uncompromising interpretation of Islam than the nuances of statecraft.

But Mr. Haqyar was different. A religious scholar, he was an expert on Islam and disagreed with certain Taliban dictates. He even wrote a book arguing that Islam promoted girls' education – though he cautiously published it under a pseudonym. When a Taliban superior found out about it, he summoned him for questioning.

"He told me to come talk and he said, 'We are not against women's education,' " recounts Haqyar. " 'We just don't have the resources.' "

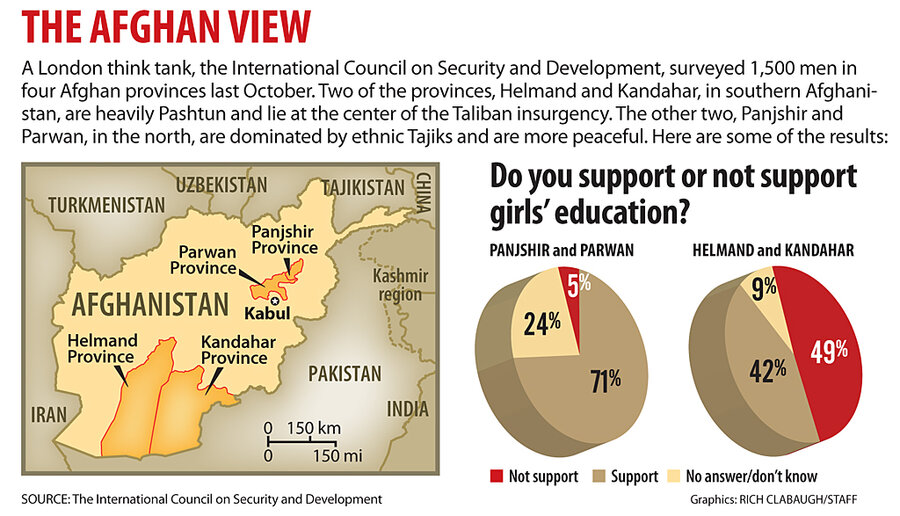

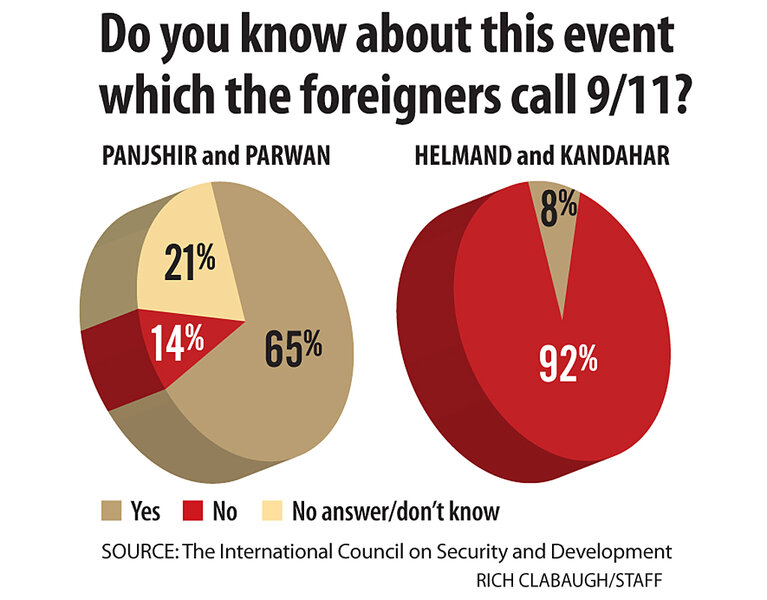

As implausible as it may sound, the assertion that the Taliban, then and now, aren't against women's education is being floated by a growing number of Taliban members and sympathizers in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Nor does the revisionist history stop at girls' schooling. Some Taliban members argue that they were misunderstood about Osama bin Laden, too. They would have handed him over to the United States – eventually.

It is all part of what appears to be a charm offensive by some elements of the Taliban – a concerted effort to soften their image in what may be a precursor to a possible political breakthrough 10 years after the advent of war.

These changes were observed before the killing of Osama Bin Laden. But the US success in targeting the Al Qaeda leader last weekend is likely to force the Taliban as well as Pakistan’s military hard-liners to look even more closely at negotiation. The US, meanwhile, will need to decide if it’s worth more years of both military and diplomatic engagement to reach an Afghan settlement, or if now is the moment simply to declare victory and begin departing.

In interviews across Afghanistan and Pakistan over the preceding two months, members of the insurgency and their supporters have sounded strikingly similar notes, almost as if reading from the same sheet music. "The world ignored us and we had no resources ... no money for girls' education and even boys' education," says one Taliban commander from Wardak Province. "If we have resources and money, we'll start doing these things."

Perhaps most significant, when the Taliban reclaimed the Pech Valley in the rugged mountains of eastern Afghanistan last month, the insurgent commander there, Haji Muhammad Dawran Safi, told the Afghan Islamic Press that they intended to keep all schools and health institutions open. He dismissed allegations that the Taliban have torched schools around the country, noting: "We do not want to deprive Afghan children of education."

So far, the schools of the region – boys' and girls' – remain open, says Khan Wali Salarzai, a reporter based in Kunar Province with Pajhwok Afghan News. "In some areas which are completely out of the government control, these schools are observed by the Taliban," who are even making sure teachers are not delinquent.

The more conciliatory rhetoric from the Taliban side – to the extent it really is conciliatory – comes at a time when the US has been signaling that it, too, might be more open to talking to the enemy, and a new vision for a postwar Afghan government is emerging. Top officials from the US, Pakistan, and Afghanistan reveal a common goal of resolving the underlying tensions that have torn Afghanistan apart for three decades – and at least the foundation of a shared vision for peace.

Under one scenario outlined by officials in all three countries in recent months, power would be rebalanced among all ethnic groups and warring parties, not just President Hamid Karzai's government and the Taliban. This would be attempted through a central coalition government and decidedly not by carving up Afghan territory among various factions.

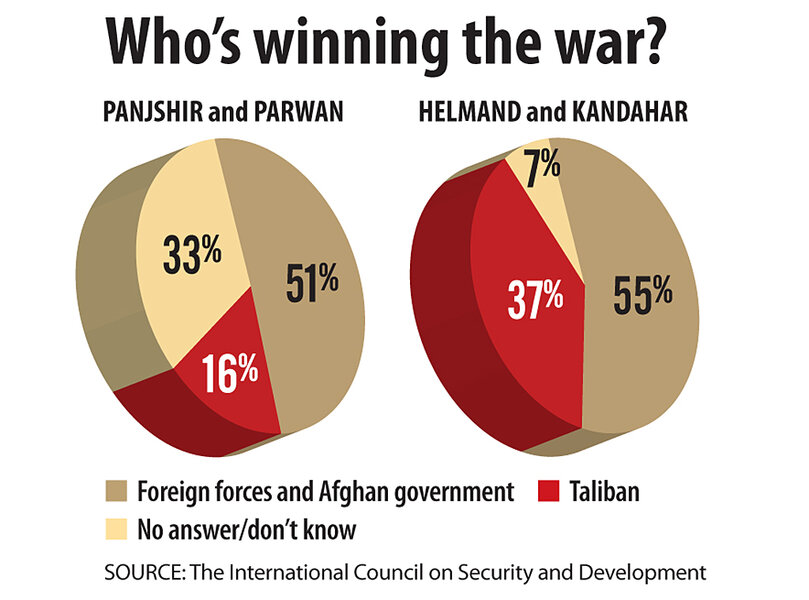

Behind the nascent political movement on both sides may be weariness over a war that has now dragged on for a decade – longer than any conflict in US history. Neither side seems poised for a quick or complete victory, the killing of Mr. bin Laden and successes of the year-old US "surge" in southern Afghanistan notwithstanding. Al Qaeda has little operational role in the Afghan insurgency. And the Taliban have responded to losses in the rural south with a series of dramatic suicide attacks inside cities and coalition ranks.

There’s also a ticking clock. The Obama administration set 2014 as the deadline for withdrawing US troops from the country.

Yet forging a peace won't be easy in a land that has lived by the sword for centuries. The US is not likely to be easily impressed by the girls-education talk from insurgents who once beat women just because their socks slipped, revealing their ankles below their burqas. An even bigger question looms over whether the Taliban are ready and capable of entering a political process that favors messy compromise over the purity of holy war.

Still, the recent seemingly calculated comments from Taliban members at least suggest the emergence of a new pragmatism.

"The talks that we are able to observe and comment on are the ones that involve everybody except the Taliban, and there's no coincidence in that," says Michael Semple, a Harvard University fellow, former diplomat, and informal mediator in the Afghan talks who frequently travels to the region. "I would say that in the contacts I have in the [insurgency] movement … they realize that politically something will happen – which is a change."

Bin Laden strike improves conditions for talks

In several ways, the knockout of bin Laden improves conditions for talks.

By sending helicopters across Pakistani territory and storming an urban compound, the strike sends a message to insurgent leaders that their havens are not so safe. It also creates an additional opportunity for the insurgency to cut links to Al Qaeda, says Rasul Bakhsh Rais, a political scientist based in Lahore, Pakistan.

The ties between Afghan insurgents and global jihadi organizations are based more on interpersonal relationships rather than ideology, he says. One key relationship, the friendship between Bin Laden and Mullah Omar, is now removed.

“Some elements may be loyal to the ideals of Osama bin Laden. But I don’t think that kind of element within the Taliban movement can win the argument when they think about their strategic priorities with Osama gone and Al Qaeda not as potent a force,” says Dr. Rais.

On the US side, the demise of Al Qaeda’s figurehead has purged some fears among Americans of the group and exposed its current weakness. And having burnished his anti-terror credentials, President Obama would have wider domestic latitude to cut a peace deal that involved insurgents who are willing to swear off any ties to Al Qaeda.

Some American officials are already downgrading the threat of Al Qaeda.

“We are going to try to take advantage of this to demonstrate to people in the area that Al Qaeda is a thing of the past, and we are hoping to bury the rest of Al Qaeda along with Osama bin Laden,” said US Homeland Security Adviser John Brennan on Monday.

But it’s unclear whether this narrative will further the push for a peace process or for declaring “mission accomplished.”

The antiwar group Rethink Afghanistan put out a petition on the heels of bin Laden’s death, saying the rationale for the war has “evaporated.” The most recent Pew polling from early April found half of Americans wanted to pull out of Afghanistan as soon as possible, with 44 percent preferring to stay until the situation is stabilized.

Some Americans express concern about mission creep, doubts that a vital national security interest remains, and skepticism that the US can stabilize the situation.

Within the region, those who view the American presence as only fueling the conflict are urging a US withdrawal as well. But others contend a lasting settlement requires ongoing American engagement.

“It all depends on what America does next – are they going to put more pressure on Pakistan [or] will they look at this opportunity as an opportunity to withdraw from Afghanistan?” says Ayesha Siddiqa, a Pakistani security analyst.

The current regime a repeat of Afghanistan's tumultuous history

Peace requires a constant gardener in the soils of Afghanistan. A search through a century of newspaper archives finds a string of dispatches about uprisings against Kabul by the Waziris, the Afridis, the Shinwaris, and other tribes on either side of the border that are at the forefront of the current conflict.

In periods of relative calm, rulers would try spurts of modernization. One article from Afghanistan in 1932 reads: "Afghan Girls Like Attending School."

These moments of spring in Kabul have frosted over because of overly ambitious governments that failed to find a balance among competing groups. Today, even supporters of Mr. Karzai's government argue that the current regime is a repeat of history. They liken the 2001 Bonn Conference in Germany, which created the Karzai government after the fall of the Taliban, to the Treaty of Paris after World War I: a victor's peace that disenfranchised the losers so much that future conflict was all but inevitable.

But negotiating a more inclusive government now, one that brings in elements of the Taliban and other insurgents, remains an epic challenge of diplomacy. "It's like designing a mission to Mars – the complexity of it is really quite great," said Stephen Biddle with the Council on Foreign Relations in an interview last year.

Yet, in the weeks before bin Laden’s death, several moves occurred that could fortify the diplomatic track in Afghanistan even as the war enters a period that is expected to be particularly violent:

•Turkey has offered to let the Taliban open an office there, according to Abdul Hakim Mujahid, the former Taliban ambassador to the United Nations and member of the High Peace Council, a body set up by Karzai to lead the peace process that includes both former Taliban members and warlords. This would establish a third-party location for talks to occur.

•Pakistan and Afghanistan have established a high-level commission to facilitate peace talks. This group has real decisionmaking power since it includes top elected officials, representatives of the foreign services, and – crucially in Pakistan – top representatives of the militaries.

Experts disagree over the degree of influence Pakistan has over the Taliban leadership. But most think that Pakistan can at least bring the Taliban to the negotiating table. Pakistani officials themselves are cagey on the question, since they want to be seen as indispensable without being viewed as playing both sides in the conflict.

"We are very clear we don't want to be [at] the table...," says Mohammad Sadiq, Pakistan's ambassador to Afghanistan. "We would like to facilitate it, support it, in whatever way is possible."

•The US has signaled it is willing to talk. In a speech in February before the Asia Society in New York, Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton said the US is ramping up a "diplomatic surge" that follows increases in military and civilian deployments.

"Now, I know that reconciling with an adversary that can be as brutal as the Taliban sounds distasteful, even unimaginable. And diplomacy would be easy if we only had to talk to our friends," said Secretary Clinton. "But that is not how one makes peace. President Reagan understood that when he sat down with the Soviets."

•The biggest breakthrough, however, may be a convergence between the US, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and even Hizb-e-Islami, one of the insurgent groups, about what the goal is: a balanced government for a unified Afghanistan.

Until recently, Pakistan appeared to be obstructing talks in order to dictate its own conditions: Any new government must be "friendly" to Pakistan and keep India at a distance. Speculation also swirled that Islamabad wanted Kabul to formalize the Durand Line, the border drawn by the British in the 19th century between the two countries, which Afghanistan has never formally recognized.

"First we have to reach a peace agreement with Pakistan, then reach a deal with the Taliban," says Khalid Pashtoon, a member of Afghanistan's parliament from Kandahar, reflecting the common perception that any peace deal goes through Islamabad.

Karzai has made several goodwill gestures toward Pakistan, including dismissing a pro-India intelligence chief, inking a transit agreement with Pakistan, and making Islamabad the first stop of his new High Peace Council.

Feeling reassured, Pakistan's leadership has been tempering its diplomatic goals. Ambassador Sadiq says his government had settled on wanting a "peaceful, prosperous, and friendly Afghanistan" but has since swapped out "friendly" for "united."

Others echo the shift. "We've dropped the word 'friendly' – it's only 'peaceful and stable' – because it's been misconstrued that Pakistan wants a government of its own [in Kabul]," says Gen. Athar Abbas, spokesman for Pakistan's military.

As Abbas tells it, the military wants to be sure that it won't have to guard the country's western border with Afghanistan in the event of another war with India. It also doesn't want agents of India to be able to cross into Pakistan through Afghanistan. "With a peaceful western border, then all those fears are addressed," he says.

While Abbas didn't mention "united," top civilian officials in Pakistan agree with the Afghan and US government aversion to dividing Afghanistan. Talk of partitions along ethnic lines has always been broadly unpopular. But some of the proposed configurations for a peace settlement had involved ceding control of certain provinces to various factions – peace through devolution.

No division of the country

US officials, however, are against handing over pieces of territory to the insurgency out of fear that it will embolden them to seek or seize more. That at least was the result of a 2006 cease-fire struck by the British in the Musa Qala district of Helmand Province. For this reason, the US doesn't want to hold talks in Afghanistan – as opposed to a place like Turkey – because it might justify creating a safe district for insurgents to come and talk, which could lead to them controlling the area.

With a division of the country ruled out, political balance must be restored through an inclusive government, say US, Pakistani, and Afghan officials. One analyst in the region argues that this is what some Taliban are seeking, too – perhaps with US help.

Insurgent leaders hoping to eventually return and resettle in Afghanistan are going to need a comprehensive peace settlement, but with a weak Afghan military and meddling neighbors, it's an open question who could safeguard such a deal. Instead, a US presence – perhaps with a UN mandate – may have to act as a guarantor for some period of time.

All this still sounds far off from Taliban rhetoric, which remains focused on removing the US and its allies. "This movement will definitely not be stopped or decreased until the foreign forces are defeated," says the Taliban commander from Wardak. "We don't believe in these shuras [councils] and these [peace] commissions – it's a political project from which these people can get money.

Also worrying is the talk coming from Pakistan's former chief of intelligence, Hamid Gul. Though retired, Mr. Gul maintains contacts with the Afghan insurgency and remains enough of a player that the High Peace Commission visited him in Islamabad.

"I don't see any chance for a coalition government," Gul said last month. "An inclusive government, yes, not a coalition." While an "inclusive" government would involve factions other than the Taliban, it would not be arrived at through Western political pluralism but by the Afghan tradition of the loya jirga, or grand council. And then – significantly – Gul added: "Mullah Omar [the Taliban's supreme leader] is the only man who can convene a jirga.”

However, the killing of bin Laden has put hard-line elements of the intelligence establishment like Gul on the defensive in Pakistan. In broadcast interviews Monday, Gul denied that the government harbored Bin Laden and suggested it was a "make-believe drama" designed to help Obama get reelected.

“They have lost face and they are so embarrassed that they are now inventing new conspiracy theories,” says Rais.

“It will help the political forces persuade the military establishment not to pursue a parallel security agenda in Afghanistan,” he adds, referring to aspirations for greater influence over Kabul.

But even if bin Laden’s death spurs greater Pakistani assistance in negotiations, the country’s credibility has been damaged.

“When it comes to bringing the Afghan Taliban leadership to the table … Pakistan is an indispensable partner,” says Anatol Lieven, author of “Pakistan: A Hard Country.” “The problem there is the US has to trust Pakistan as a broker. What just happened makes that considerably more difficult.”

Trust is severely lacking

Any negotiating in a peace process would require an element of trust among the parties – something severely lacking in this conflict. Yet a willingness to at least talk is springing forth from unlikely places.

In a leafy corner of Pakistan's capital, Ghairat Baheer welcomes three reporters into his multistory home. "Would you like some tea or coffee?" he asks, following up shortly thereafter with a platter of sweet biscuits.

In the middle of a night in 2002, he had a different set of visitors to his house: gunmen who whisked him away, eventually to Afghanistan. For six months, the US military confined him to a dark cell measuring 6 feet by 8 feet at a CIA prison in Kabul, he says. "My toilet was a small bucket," recalls Mr. Baheer. "I was given a meal each 48 hours – sometimes 24 hours. I used to eat in darkness; I couldn't see the plate."

He says he was tortured, including being suspended from the ceiling by his arms. (Another detainee at the site, known as the Salt Pit, died at the time. The CIA's inspector general forwarded the case to federal prosecutors, who later dropped it, according to the Associated Press.) Eventually Baheer was brought to the prison at the US's Bagram Air Base outside Kabul.

Baheer says he's never been a militant. Instead, he serves as head of the political wing for a faction of Hizb-e-Islami headed by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar. Before the Taliban came to power, Mr. Hekmatyar served as prime minister of Afghanistan and Baheer, his son-in-law, was the country's ambassador to Pakistan.

Hekmatyar earned a bloody reputation for his role in rocketing Kabul during the struggle among the mujahideen factions that fought over the capital after the Soviets left. Few leaders emerged from those years with good names, including rival Northern Alliance commanders now backed by the US and leading the Karzai government.

Hekmatyar's group was "ignored" at Bonn – it was a "joke," says Baheer – and has become a third component of the Afghan insurgency along with the Taliban and the Haqqani network.

In the Bagram prison, Baheer says he eventually won over the Americans with long talks about politics and his help in negotiating with detainees. From his six years in detention, he estimates that he now knows about 2,000 to 3,000 Americans by sight. He says he has worked hard to let go of his anger about what the Americans have done to him and his country.

"I didn't let the hatred develop in my body towards even Americans," says Baheer. "I was a politician, and I knew in my future the time would come that again we would be talking to each other. If you have hatred toward someone, then you aren't talking to them from the bottom of your heart."

While Baheer might be willing to engage in new peace negotiations, it wouldn't simply be a matter of showing up at some conference center for talks. In the complicated world of Afghan politics, even getting to the negotiating table can be tricky.

Some of the top insurgents have spent years in harsh detention or on a UN blacklist. They fear they will be detained if they travel outside their protected territories. It's a reminder of the mistrust that exists on all sides, a mistrust rooted in painful memories – of torture on one side and of fanatics flying airplanes into skyscrapers on the other.

The UN has begun removing some names from its blacklist. But even former Taliban who now sit on Karzai's High Peace Council remain listed. Fixing this issue won't be easy. According to Western officials in Afghanistan, Russia, as a member of the Security Council, must agree to any changes, and Moscow views this as valuable leverage. It's one of the many trump cards being held in the top floors of embassies, the "poppy palaces" of warlords, and the underworld havens of insurgent leaders when it comes to trying to launch peace talks.

"The downside of this whole thing: There are too many people who are trying to reconcile," says Sadiq, the Pakistani ambassador.

A lack of American support?

Since his release, Baheer has represented Hizb-e-Islami in talks with Karzai's government. Yet those negotiations failed last year due to a lack of American support, he claims – something echoed by Karzai administration officials.

On paper, Hekmatyar is demanding withdrawal of foreign forces and changes to the Afghan Constitution. In the interview, Baheer wouldn't get specific on constitutional changes, but said his party has always believed in women's education and suggested flexibility on troop withdrawal, saying it should be "according to logical, acceptable, and practical timetables."

Officially, the Taliban still set withdrawal as a precondition for talks – a nonstarter for the US. As one of Afghanistan's longest-running political parties, though, Hizb-e-Islami has more experience with compromise and the art of politics. "I am trying to talk with [the Taliban] to come up with something practical. This stand is not logical to say 'no' to everything," says Baheer.

Ultimately, he sees a new government being formed with many different players. "The Taliban were rigid and lacking the experience of running a country. But they have learned, and there will be a lot more political players in Afghanistan."

But are the Taliban really ready to talk and, more crucially, enter a political process? Their official statements are not encouraging. They have rejected the High Peace Council formed by Karzai to lead the process, even though the Afghan leader designated the council a nongovernmental organization to overcome the Taliban refusal to meet with the Afghan government.

Parsing Taliban statements

Given the limited access to top Taliban figures, experts have to parse their intents and interests from statements and shards of information – an Afghan version of the old cold-war Kremlinology. One of these experts is Wahid Mujda, himself a former Taliban official.

In an interview last year, Mr. Mujda noted that as far back as March 2009 the statements from the Taliban were moderating. A new political chief for the group sent out a message to the Muslim world asking citizens to not revolt against governments. (This predated the events touched off in Tunisia this spring.) The rationale was that revolts would bring deeper US meddling in the Middle East. The statement intrigued Mujda.

"It was against Al Qaeda opinion, because Al Qaeda wants a revolution all over the Muslim world," Mujda explained last year. He asked his Taliban contacts if this statement was official and if it meant a severing of ties with Al Qaeda. A contact close to Mullah Omar replied that it was the Taliban's position, and hinted that the message was really a signal that they wanted to talk peace.

"That means we are ready to talk and have negotiations with the Afghan government and the US, but [US officials] never accepted that because they want to ignore us and say we don't understand their messages. We have sent a lot of messages to these people, but they never listen," Mujda said the contact told him.

Mr. Semple, another of the new Kremlinologists, reads the latest rhetoric on girls' education from Taliban commanders as a similar signal to the US. "They are certainly trying to make themselves more palatable," says Semple. He cautions, though, that "it's not just that they need to be palatable to the international community, but they need to be prepared to contemplate political compromise with fellow Afghans."

Still, even if the Taliban were ready to talk, there is no guarantee all elements would speak with one voice. Omar himself has struggled over the years to retain control of the disparate movement. Most notably, the cleric has released handbooks of conduct for Taliban fighters that argued against needless targeting of civilians, but there have since been numerous suicide attacks on so-called soft targets.

"The Taliban is not a central system. Some people are listening to the main shura; some are not," says Sami Yousafzai, a senior Pakistani journalist who has met with top Taliban leaders. "Omar is not in physical contact with anyone."

Since taking command of the NATO effort in Afghanistan, Gen. David Petraeus has targeted mid-level commanders, killing many. That has helped sever some of the ties between the leadership and those in the field. But it's also emboldened a younger generation of Taliban who are in many ways more extreme.

"There is a saying that the older [Taliban] will not kill you for at least five hours; the new will just kill you on the spot," says Mr. Yousafzai.

The new Taliban are more versed in information technology, too. They frequently peruse Al Qaeda and Taliban websites, he says. When it comes to a possible peace deal, the leadership may have trouble bringing the younger generation along.

"The older [Taliban] who served in government as ministers or deputy ministers, at least they have an idea, if they are coming to reconciliation, what their [government] role would look like," says Yousafzai. "But the new generation has no idea. They just fight jihad."

Still, despite the considerable obstacles to any kind of peace process, there seems to be at least some movement on the long-moribund diplomatic side of the Afghan conflict. Those halting steps, to be sure, will likely be driven by how America and Pakistan work together after Osama bin Laden's killing and whether the Taliban can sow doubt again about the US commitment to the war and the peace.