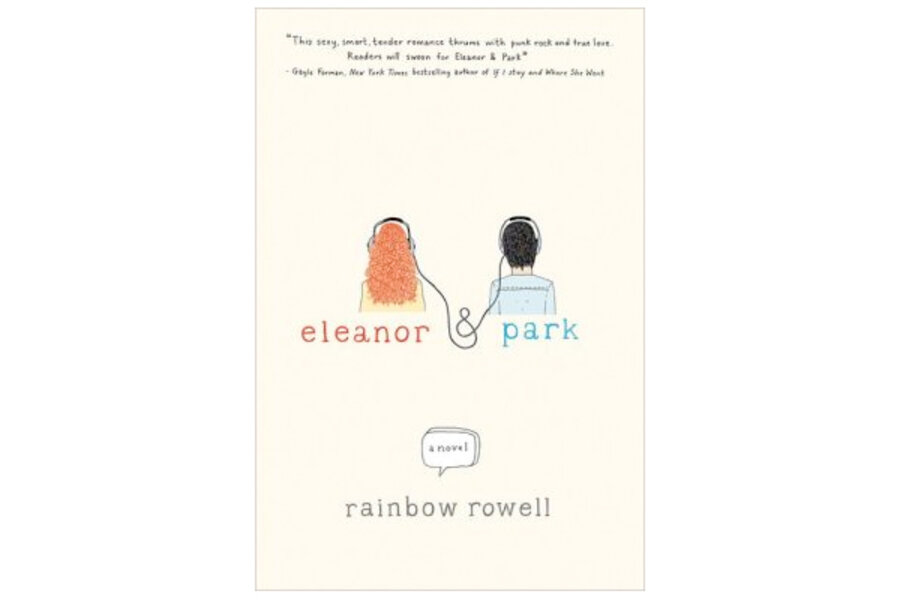

Eleanor & Park

Loading...

Of all the young adult novels published in 2013, Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell has emerged as the clear favorite of fans and critics alike. It’s the tale of two 16-year-old misfits falling in love during one school year in 1986. As befits a love story set to punk rock and mixtapes, it’s intense and lyrical.

Eleanor Douglas is new in Omaha. A year after her alcoholic stepfather kicked her out of the house, she’s moved back in with her siblings, mother, and stepdad Richie. Richie rules the house with fear, invective, and physical abuse, and he’s not exactly pleased to have her back.

Everything about Eleanor is big (“At sixteen, Eleanor was already built like she ran a medieval pub”) except her self-worth, worn down by years of abuse and abandonment. Her peers torment her for her wild red hair and oddball style (curtain tassels in her hair, men’s spiked golf shoes), and someone keeps writing threateningly sexual messages on her notebooks.

Park Sheridan is half Korean, half Irish-American. He’s lived a sort of Mayberry life: His parents have always been madly in love, his grandparents live down the street, and he’s gone to school with the same kids his whole life. He’s well-versed in comic books, taekwondo, and rock music, and his Walkman is full of '80s punk: Joy Division, The Cure, The Misfits, The Smiths.

(Side note about the music in "Eleanor & Park": Shortly after the book came out, Rowell blogged about her own playlists, full of Park’s favorite songs plus mood-setting music. For those who’ve read "Eleanor & Park" and for those who haven’t (but should!), the playlists are a great companion.)

Eleanor and Park meet as reluctant bus seat partners. Eleanor sits very still and tries to ignore her classmates’ harassment and Park hides behind comic books and his Walkman. At first their interaction is confined to uncomfortable glances. Yet when he notices her reading the comics over his shoulder, they awkwardly become friends and then fall in love.

Their love is sweet, sexy, clever, and raw. They’re crazy about each other in that all-encompassing first love way, yet Eleanor’s dysfunctional history threatens to rupture them before they can even really begin. Eleanor feels deep down that they have an expiration date, that she must soak up as much Park – as much of the best thing she has ever had or perhaps will ever have – as she can, in the little time that she expects to have him.

Rowell writes with the witty wonderment of someone experiencing love for the first time. Her marvelous, clear voice is like a sharp intake of breath. She describes emotions and experiences so vividly that I found myself reliving memories of my own first love – which made "Eleanor & Park" all the more captivating.

Do you remember the first time you held someone’s hand? It’s a thrilling, foreign, time-warping moment, and Rowell nails it:

“Holding Eleanor’s hand was like holding a butterfly. Or a heartbeat.… Park touched her hands like they were something rare and precious, … How could it be possible that there were that many nerve endings all in one place? And were they always there, or did they just flip on whenever they felt like it? Because, if they were always there, how did she manage to turn doorknobs without fainting? Maybe this was why so many people said it felt better to drive a stick shift.”

Yet far from being a cheerful romcom, "Eleanor & Park" thrums with intensity and often fear. The students’ bullying is real and horrifying, and Eleanor’s home life never strays from terror. And when she discovers who’s been writing the sick, menacing notes on her books, Eleanor needs to leave town – right away.

Eleanor and Park struggle to define themselves, love themselves, and interact with others. "Eleanor & Park" echoes this struggle on several levels: children-parents, teens-friends, teens-lovers, students-teachers, and adults-adults.

Adolescence revolves around identity and acceptance. It’s an endless quest to define one’s world. Who am I? Do I accept myself? Will others? Where do I belong? In "Eleanor & Park" as in Veronica Roth's blockbuster "Allegiant," defining one’s self is the most important part of growing up.

This is what I love about YA novels – they’re ostensibly about teens, but they’re hardly teenage themes. The concepts that YA characters tackle are universal: identity, vocation, love, transformation. The protagonists question why we do things and why we are who/what we are.

It’s no wonder, then, that so many adults love to read YA literature. It causes us to remember our own experiences and to rethink them in a new light. Readers (both teen and adult) must face the difference between, and the intersection of, our past and present selves.

Observant. Incisive. Tense, yet buoyant with hope. "Eleanor & Park" is constructed like a Swiss watch: tightly knit and perfectly paced. This book is well deserving of its status as 2013’s best young adult novel.

(Heads-up: There's some sexual content and plenty of edgy language.)

Katie Ward Beim-Esche is a Monitor contributor.