Are your checks safe? Fraud surges, targeting vulnerable groups.

Loading...

| New York

Check fraud is back in a big way, fueled by a rise in organized crime that is forcing small businesses and individuals to take additional safety measures or to avoid sending checks through the mail altogether.

Banks issued roughly 680,000 reports of check fraud to the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, also known as FinCEN, last year. That’s up from 350,000 reports in 2021. Meanwhile, the U.S. Postal Inspection Service reported roughly 300,000 complaints of mail theft in 2021, more than double the prior year’s total.

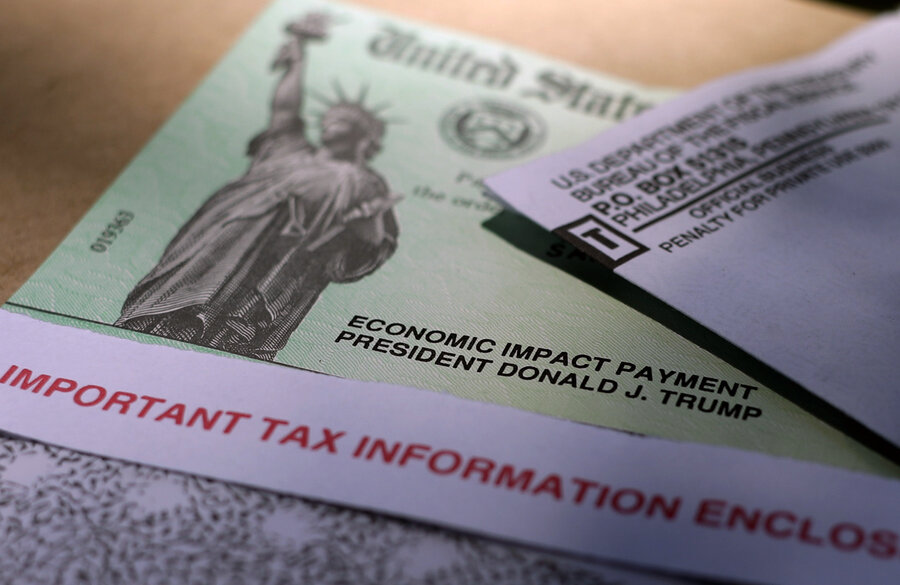

Early in the pandemic, government relief checks became an attractive target for criminals. The problem has only worsened and postal authorities and bank officials are warning Americans to avoid mailing checks if possible, or at least to use a secure mail drop such as inside the post office. Meanwhile, as the cases of fraud increase, victims are waiting longer to recover their stolen money.

Check usage has been in decline for decades as Americans have largely switched to paying for their services with credit and debit cards. Americans wrote roughly 3.4 billion checks in 2022, down from nearly 19 billion checks in 1990, according to the Federal Reserve. However, the average size of the checks Americans write rose from $673 in 1990 – or $1,602 in today’s dollars – to $2,652 last year.

“Despite the declining use of checks in the United States, criminals have been increasingly targeting the U.S. mail since the COVID-19 pandemic to commit check fraud,” FinCEN wrote in an alert sent out in February.

Checks are still frequently used by small businesses. Eric Fischgrund, who runs FischTank PR, a 30-person public relations firm in New York, had about 15 checks that were being mailed to him from clients stolen after they all went through the same Postal Service distribution center. Ten of them were successfully cashed by criminals.

The checks were stolen in March and Mr. Fischgrund became aware of the problem in April, when several of his clients who were never late missed payments. The Postal Service investigated and Mr. Fischgrund has recovered about 70% of the revenue, but some of the cases haven’t yet been resolved.

According to the investigator on the case, the perpetrators used technology that melted ink in the “to” field of the checks so they could write in fake names. FischTank instructed all its clients to change their paper format because it was dealing with a check fraud issue.

Mr. Fischgrund said he’d never previously had an issue with check fraud in the nearly 10 years he has run his own business. Now he has a clause in invoices and new client contracts that asks for electronic payments only.

“I don’t think we’ll ever go back to asking for checks as an option,” he said.

Today’s check fraud criminals are not small operations, or lone individuals like the Leonardo DiCaprio character in the 2002 movie “Catch Me If You Can,” counterfeiting checks from his hotel room and apartment. They are sophisticated criminal operations, with participants infiltrating post office distribution centers, setting up fake businesses, or creating fake IDs to deposit the checks. “Walkers,” or people who actually walk in to cash these checks, receive training in how to appear even more legitimate.

In one case in Southern California last year, nearly 60 people were arrested on charges of committing more than $5 million in check fraud against 750 people.

Criminals are getting the checks or identification information by fishing mail out of U.S. postal boxes, looking for envelopes that appear to be either bill payments or checks being mailed.

The most common type of check fraud is what’s known as check washing, where a criminal steals the check from the mail and proceeds to change the payee’s name on the check and, additionally, the amount of money.

Some criminals are going further and using the information found on a check to gather sensitive personal data on a potential victim. There have been reports of criminals creating fake entities out of personal data obtained from a check, or even opening new lines of credit or businesses with that data as well. This allows fraudsters to create new checks using old account data.

That’s why check fraud experts are saying Americans should avoid sending checks in the mail or at least take additional safety steps to avoid becoming a victim.

“If you need to mail a check, do not put a check in your residential mailbox and raise the flag to notify the postman. Drop off checks inside a post office if you have to,” said Todd Robertson with Argo Data, a financial data provider.

Banks, keenly aware of the problem, are increasingly watching for signs of fraud at branches and through mobile check deposit services, including large check deposits. They’re training branch employees to take steps such as looking at check numbers, because checks are typically written in order, or noticing when a check is being written for a much larger amount than the customer’s previous history would indicate. Banks also now deploy software at their branches that can tell how risky a check might be.

But those systems become moot if criminals are able to persuade tellers – often at the front lines for check acceptance – to look past any red flags.

“These fraudsters are much more aggressive than they were in the past, and they are pressuring tellers to override internal systems that might flag a potentially suspicious transaction,” Paul Brenda, a senior vice president at the American Bankers Association.

Banks generally reimburse customers if they are victims of check fraud within days. However, due to the growing number of fraud cases, refunds have slowed down in recent months. In March, a trio of Democratic Senators asked the banking industry to be more prompt in reimbursing victims of check fraud whenever possible.

Another safety tip for businesses is to opt in to a bank’s “positive pay” services with a business checking account. Positive pay means you pre-authorize checks for a certain amount as well as the check number, cutting down criminals’ ability to wash the check and withdraw money for an amount that isn’t pre-authorized.

This story was reported by The Associated Press. AP Small Business Writer Mae Anderson contributed to this report from New York.