Imperturbable ytterbium reverberates superbly, scientists say

Loading...

Using lasers and a rare metal element called ytterbium, scientists at the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) say they have crafted a pair of the world's most stable timepieces.

According to research published in the current issue of the journal Science, the new clocks are stable to within one part in a quintillion (that's a one with 18 zeros after it). By comparison, your bog-standard quartz clock is stable to roughly six parts in a million, drifting off by about a second every two days. The new clock is roughly 10 times more stable than its predecessors, NIST says.

The stability of these clocks "opens the door to a number of exciting practical applications of high-performance timekeeping," says NIST physicist and co-author Andrew Ludlow, in a press release.

Atomic clocks, which are used to calibrate sensitive electronics such as those used by global positioning systems and to conduct sensitive experiments in fields as diverse as geology, particle physics, and radio astronomy, rely on the vibrations of atoms. Each element has its own natural vibration rate, and if you know what that rate is, you can use it to keep time.

For instance, the NIST-F1 cesium fountain clock, which establishes the official US time, works by zapping atoms of a stable isotope of the element cesium called cesium 133 with microwave beams and then measuring the rate at which these excited atoms emit photons. An international agreement in 1967 defined one second as exactly 9,192,631,770 vibrations of a cesium 133 atom.

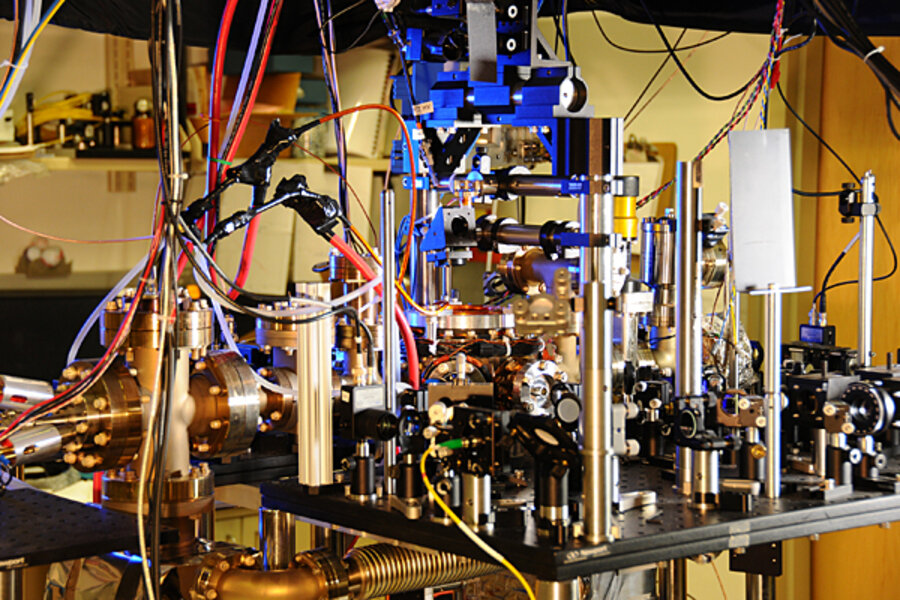

Instead of microwaves, this new pair of clocks uses lasers to excite the atoms. And instead of cesium, it uses ytterbium, a rare metal named after the Swedish village Ytterby, near where it was first discovered (the little village has also given us the names of the elements yttrium, terbium, and erbium).

The clock works by taking about 10,000 ytterbium atoms and cooling them to within a hair of absolute zero. The atoms are held in place by an "optical lattice" of laser light, and then another laser is used to stimulate the atoms so they vibrate.

The average cesium clock must run for about five days before its ticking stabilizes. By contrast, these ytterbium clocks achieve stability in about one second. The researchers credit this improvement to the large number of ytterbium atoms and to the improved accuracy of the lasers.

So just how stable are these new clocks? If NIST's claims are accurate, if the clock were to start running at the beginning of the universe, about 13.8 billion years ago, by now it would be off by just one second, according to an MIT physicist quoted by Eryn Brown of the Los Angeles Times.