Before you say “But the iPad!”, we’re not talking Apple. Microsoft actually released a tablet PC 10 years before the iPad came out, but couldn’t get it to take off the way the iPad did in 2010.

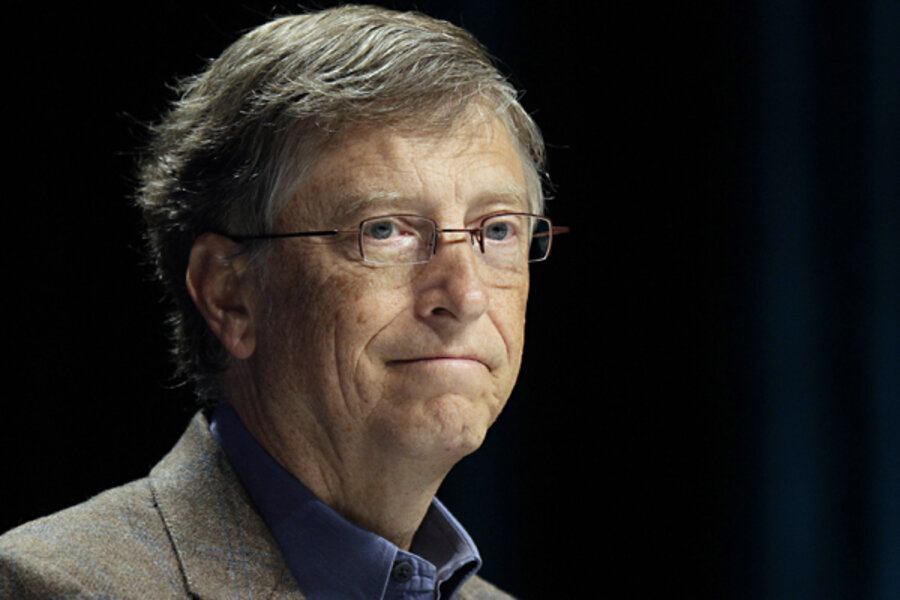

Originally dubbed the “Tablet PC,” the tablet was a functional Windows computer, not much bigger than the iPad, that was controlled by a stylus. When it was released, Bill Gates boasted that within five years tablets “will be the most popular form of PC sold in America.” Not quite. It caught on with businesses and healthcare facilities, but not with the general public. Why? Cost, function, and the elusive touch screen. The original Windows tablet cost more than $2,000 and crammed Windows (software designed for a mouse and keyboard) into a device that didn't use either. Plus, Gates believed people would use it just like they had a desktop computer, rather than as a stand alone device. The software weighed down the tablet, and Gates failed to explain why it was such an innovation.

Apple did the opposite. The iPad is not a tablet PC – it's just a tablet. It wound up being more important because it did less. When the iPad came out, it ran on a separate operating system specifically designed for tablets, plus with a range of applications that used the portable tablet design (like online versions of magazines and social networking sites). Plus it did away with the clunky stylus, and made capacitive touch screens the clear industry standard. Since then, Microsoft certainly hasn’t dropped out of the tablet game – it just came out with two new models of its ‘Surface’ tablet. But by not recognizing the full value of the tablet in 2001, it passed the world-changing torch straight to Apple.