Secrets of ancient Venetian glassmaking revealed

Loading...

| Albany, N.Y.

A modern-day glassblower believes he has unraveled the mysteries of Renaissance-era Venetian glassmaking, a trade whose secrets were so closely guarded that anyone who divulged them faced the prospect of death.

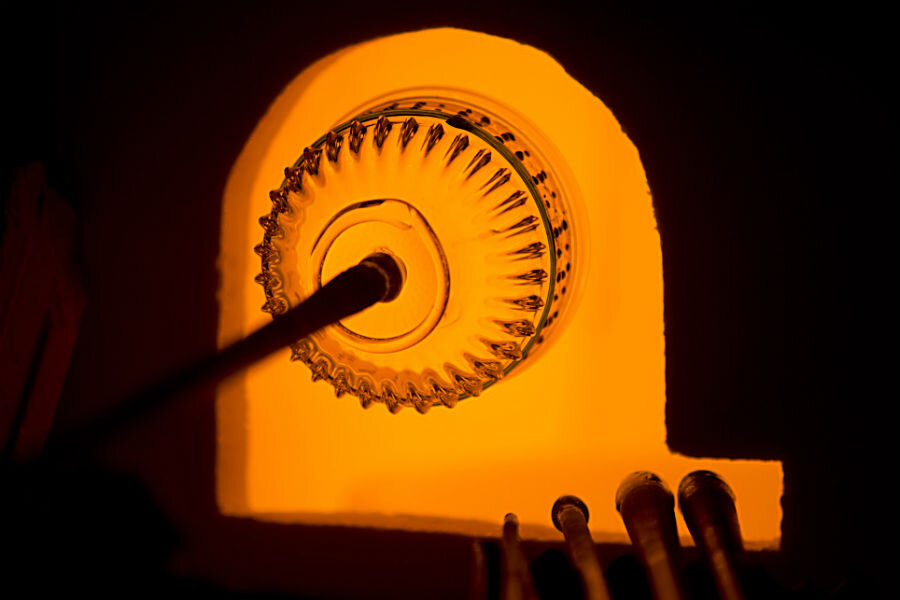

Today's glassblowers work with methane-fired furnaces, electric-powered kilns, good lighting and proper ventilation. The craftsmen of Murano, an island near Venice, didn't have such technology, yet they still turned out museum-worthy pieces known for their artistry and beauty, using techniques that remained exclusive for centuries.

Through years of researching Venetian glass collections at American and European museums and comparing the artifacts with more contemporary glasswork from Venice, plus his own experimentation and many trips to Italy, William Gudenrath has created an online resource he believes explains Venetian glassmakers' methods.

"The Techniques of Renaissance Venetian Glassworking" — which contains videos, photographs and text — details how Gudenrath surmises glassworkers produced works of art with little more than wood-fired furnaces and metal blow pipes and tongs. The information was posted this week on the website of the Corning Museum of Glass in upstate New York, where Gudenrath is a resident adviser and teacher of Venetian techniques.

The gilding and enameling the Murano glassmakers added to their glass products had to be fired at higher temperatures than the glass itself to make the decorations permanent. The Venetians couldn't simply turn a nob to regulate the temperature of their furnaces, Gudenrath said, yet they mastered the tricky art of glass decoration by continuously reheating and shaping the vessel after the decorations had been added, a process he demonstrates in several videos.

"It's just amazing to me that they did what they did in those conditions," he said.

On the website, Gudenrath writes:

It would be difficult to find a more unlikely place for locating a glass industry than on the islands of Venice and Murano, which are small and surrounded by shallow waters. None of the essential elements involved in the making of glass were either native or located nearby. Even with Venice’s unmatched mercantile fleets in the Middle Ages and later, it must have been costly and difficult to meet the glassworkers’ incessant need for supplies

Gudenrath's knowledge of Venetian glassmaking and his research into the process, something he has focused on for 25 years, are a "fantastic resource for artists," said Jutta-Annette Page, curator of glass and decorative arts at Ohio's Toledo Museum of Art.

Gudenrath, 65, became fascinated with Venetian glass while a teenager in Houston, where he started blowing glass at age 11. But finding written documents detailing how Murano glass was created proved difficult, a result of restrictions placed on the trade hundreds of years ago.

To prevent fires, the Venetian government ordered glass furnaces moved to Murano in the late 13th century. The move also was aimed to prevent secrets of the glassmaking guild from being smuggled to competitors. Anyone attempting to do so could be executed under Venetian laws created to maintain the city's monopoly on the European luxury glass trade.

"Industrial espionage and that sort of thing was taken very seriously," Gudenrath said.

Competition from other European nations eventually weakened Murano's hold, and Napoleon's closing of the factories after conquering Venice sent the industry into further decline. Venetian glass experienced a rebirth in the mid-19th century, but Gudenrath said much of the practical knowledge of the original, secretive methods had been lost.

Some of the old techniques have been reinvented and are being again used on Murano, still home to vibrant, albeit smaller, glassmaking operations and studios.

___

Associated Press writers Michael Hill in Albany and Mike Householder in Detroit contributed to this report.