AI in the classroom: Why some teachers are embracing it

Loading...

In Georgia, educators are thinking more about what students should be learning about artificial intelligence. Their vision has started to become a reality. The youngest learners are having conversations about household appliances, such as Amazon’s Alexa. High schoolers can now take classes that culminate in using AI to solve real-world problems.

“What we’re really trying to do is teach our students how to be critical thinkers,” says Sallie Holloway, director of artificial intelligence and computer science for Gwinnett County Public Schools.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onEducators are trying to balance concerns about artificial intelligence with how to prepare students for using it in the future. What does teaching look like when AI is part of the curriculum?

School-based computer labs once seemed futuristic. Now the internet is everywhere, and the next frontier – AI – is seeping into learning environments. ChatGPT’s debut more than a year ago brought ongoing concerns about cheating and the tool’s ability to mislead students. But some educators also see it as an opportunity for innovation.

Everything from smartphone apps to collision-avoidance systems on cars use AI, with experts saying that it will soon be embedded in daily life.

“It’s not just like textbook work,” says Carter Watkins, a senior at Gwinnett County’s Seckinger High School. “You’re putting your thinking cap on.”

What if instead of being wary about artificial intelligence, schools were embracing it?

In Georgia, educators in a district near Atlanta are thinking more about what students should be learning about AI. Their vision has started to become a reality. The youngest learners are having conversations about household appliances, such as Amazon’s Alexa. High schoolers can now take classes that culminate in using AI to solve real-world problems.

“What we’re really trying to do is teach our students how to be critical thinkers,” says Sallie Holloway, director of artificial intelligence and computer science for Gwinnett County Public Schools.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onEducators are trying to balance concerns about artificial intelligence with how to prepare students for using it in the future. What does teaching look like when AI is part of the curriculum?

School-based computer labs once seemed futuristic. Now the internet is everywhere and the next frontier – AI – is seeping into learning environments. ChatGPT’s debut more than a year ago brought ongoing concerns about cheating and the tool’s ability to mislead students. But some educators also see it as an opportunity for innovation.

David Touretzky chairs the Artificial Intelligence for K-12 Initiative, which began in 2018 after he realized computer science standards had barely mentioned the burgeoning AI field. The group has been developing instructional guidelines, establishing what students should know about AI, and how they should be able to use it.

Everything from smartphone apps to collision-avoidance systems on cars uses AI. And with the emergence of large language models like ChatGPT, which rely on vast amounts of data, AI will become even more embedded in daily life, Mr. Touretzky says, explaining the need for related education.

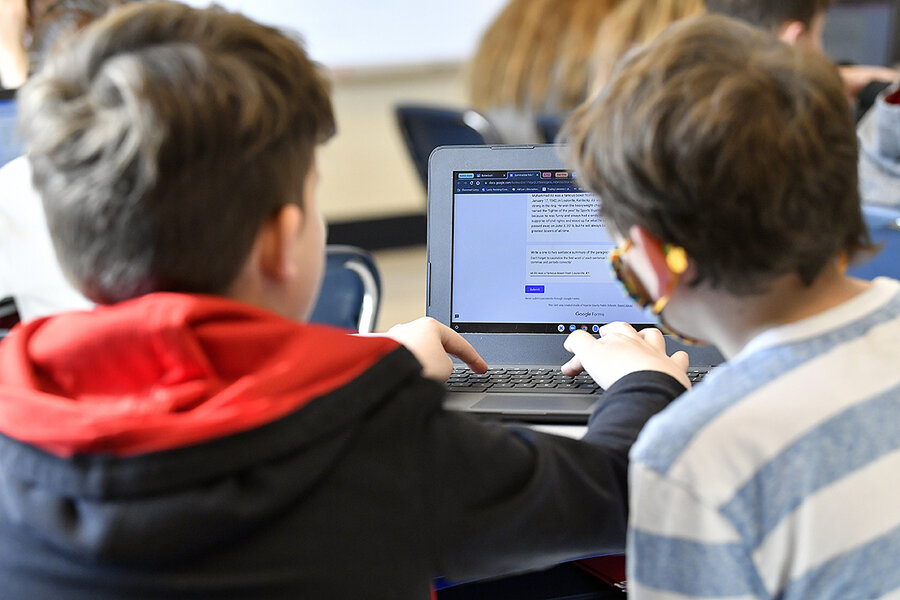

The Artificial Intelligence for K-12 Initiative has been piloting an AI elective course in some Georgia middle schools that includes topics such as autonomous robots and vehicles and how computers understand language and make decisions.

“The way kids relate to AI is going to depend a lot on how large language models find their way into our society,” says Mr. Touretzky, who is a research professor in computer science at Carnegie Mellon University. “We don’t understand yet what that’s going to look like.”

Preparing for the future

In October, the Center on Reinventing Public Education found that only two U.S. states – California and Oregon – had issued specific guidance surrounding AI education.

Officials from Gwinnett County Public Schools liken the academic imperative to driving a car. Before people get behind the wheel, they need to know the rules of the road and the basics of vehicle maintenance. Artificial intelligence necessitates a similar education, they say.

An AI-ready student, as defined by the district, would be exposed to, if not well versed in, the areas of data science, mathematical reasoning, creative problem-solving, ethics, applied experiences, and programming. At a pilot group of schools, the district has embedded this learning framework in kindergarten through 12th grade classrooms.

“Students are hearing every day about how pervasive AI is and how it is in every industry,” says Ms. Holloway of the work she coordinates. “So I think they are interested to know more and really prepare themselves for their futures.”

Carter Watkins, a senior at Seckinger High School in Buford, part of the Gwinnett district, says the inclusion of AI throughout his core subjects has made him more eager to attend school. He particularly enjoyed a lab activity in a physics class, in which students leaned on AI to help determine which remote control car moved faster with different batteries.

“It’s not just like textbook work,” he says. “You’re putting your thinking cap on.”

As an aspiring business major who wants to go into sports marketing, Carter says the AI skills are helping him become a “more well-rounded individual.”

“AI is not all bad”

With or without official guidance, some educators are already displaying how it can be used for good.

At Highlands Ranch High School outside of Denver, Principal Chris Page Jr. used artificial intelligence to develop clues for a homecoming-related scavenger hunt. He drew inspiration from AI and tinkered with the suggestions.

After students solved the mystery, he let them in on his secret. Dr. Page says he wants his staff and students to know there are benefits to AI if it is used correctly – just like prior technology that seemed unnerving at first.

“AI is not all bad,” he says. “What we know to be true is there are always educational shifts, and a lot of those are technological shifts in education.”

Experts say weaving AI into lesson plans will be a gradual process, partly because teachers need to learn the technology, too. An Education Week survey conducted in the fall found that two-thirds of teachers had not used AI tools in the classroom. Of those, more than a third had no plans to use it, while about another third envision using it soon.

When educators at Dr. Page’s school use AI in the classroom, the lessons mostly familiarize students with its capabilities and drawbacks, he says. Teachers, for instance, may have AI generate a historical narrative and then have students dissect it to determine what’s true and false.

The “research-minded” project, he says, allows students to “truly become historians because that’s what historians do.”

In the Los Angeles area, a charter network called Da Vinci Schools has deployed AI in the form of Project Leo. The platform melds instructional standards with student interests, producing project ideas that personalize learning, says Steve Eno, who teaches mechanical engineering and is the director of Project Leo.

He says one student is devising a “trick analyzer” using AI technology that will offer recommendations about how skateboarders can improve their form.

“I don’t think every kid is going to be interested in using AI to build,” Mr. Eno says. “I do think students need to know how it works and what’s possible with it.”

Sometimes Project Leo spits out ideas either that are bad or that students don’t like. That’s OK, he says, because it’s showing them the imperfections surrounding AI. But when an AI-generated project idea sparks a student’s imagination, it leads to more engagement and, ultimately, a portfolio of work that can lead to future careers, Mr. Eno says.

“They need to be excited,” he says. “They need to be joyful, and then they’ll actually learn the stuff.”