When it comes to opioid crisis, what does justice look like?

Loading...

Who bears responsibility for the opioid crisis, and how should that be equitably apportioned?

That’s at the heart of two major developments in the legal battles over whether drug companies should be forced to pay for at least a portion of the estimated $1 trillion cost of the opioid crisis in America, which has left more than 400,000 people dead from overdoses.

Why We Wrote This

What would represent justice in the opioid crisis? This week, a ruling and a settlement offer suggest paths forward, but can litigation alone offer a solution?

On Monday, Oklahoma – the first state to go to trial against an opioid manufacturer – won its case against Johnson & Johnson, which was ordered to pay $572 million. And Tuesday, news reports revealed a $10 billion to $12 billion global settlement offer from Purdue Pharma. But the deals may not be commensurate, or fair, experts says, given the two companies’ roles in the opioid crisis, and their respective financial resources.

“The big problem is a lot of harm is already done,” says Adam Zimmerman, a professor at Loyola Law School. “How do we remediate that problem? What is the price of dealing with that problem? And to what extent are defendants in these cases responsible for this problem?”

“That’s going to remain a huge sticking point,” he adds. “How do you put a price on the opioid crisis?”

The legal battle in courtrooms around the country over who is responsible for the opioid crisis, and who should pay to fix it, took two major steps toward a conclusion this week.

On Monday, in the first opioid case to actually go to trial, a judge in Oklahoma ruled that pharmaceutical giant Johnson & Johnson helped fuel the crisis in the state, and ordered the company to pay $572 million this year toward treatment programs and other initiatives.

Barely 24 hours later, reports emerged that the owners of Purdue Pharma, the maker of the painkiller OxyContin, are offering to settle more than 2,000 lawsuits against the company for $10 to $12 billion. Purdue settled a separate lawsuit in Oklahoma for $270 million in March.

Why We Wrote This

What would represent justice in the opioid crisis? This week, a ruling and a settlement offer suggest paths forward, but can litigation alone offer a solution?

More than 400,000 Americans have died from opioid overdoses since 1999. The epidemic’s cost to communities and governments around the country is in excess of $1 trillion. Both Oklahoma’s lawsuit and the consolidated cases against Purdue Pharma place responsibility for the crisis squarely on drug manufacturers, and seek to make them pay for the costs of the epidemic to individuals, communities, and government resources.

But even as some cheer these milestones, the Purdue settlement and Johnson & Johnson verdict represent a fraction of the estimated cost of the opioid crisis in the United States and Oklahoma, respectively. That suggests that the question of who bears responsibility and whether they can be compelled to pay for the fallout remains far from resolved.

“They’ve created the problem, or at least substantially contributed to it, and shouldn’t be allowed to walk away and leave someone else holding the bag,” says Richard Ausness, a professor at the University of Kentucky College of Law in Lexington, but he adds that there has to be a balance. “They should certainly contribute to solving the problem. It should be substantial, but it shouldn’t be enough to cripple them or put them out of business.”

Among the issues remaining to address are how to make these settlements and court rulings proportional and fair; what, if anything, a company can do to make things right; and whether other parties bear responsibility as well, such as pharmacists, doctors, or even the individuals who took the drugs.

Shawna Covington, an Oklahoman who lost her mom to prescription opioid abuse, says she could never understand how it was so easy for her mom to obtain so many drugs. Why, she wondered, didn’t it set off a red flag at pharmacies, where on top of numerous other pills her mother was able to get huge bottles of OxyContin? And it was all done legally, with a prescription from her mom’s long-time doctor.

“I do think it was marketed and the pharmaceutical companies are responsible, yes. But ... the doctor has to take some ownership as well,” says Ms. Covington. “I don’t sit up at night thinking of Johnson & Johnson. I think of this doctor.”

A public nuisance

Johnson & Johnson is the first company to be judged legally culpable for fueling the opioid epidemic. Oklahoma, which has lost more than 6,000 residents to painkiller overdoses since 2000, sued three companies in 2017 but the other two settled out of court.

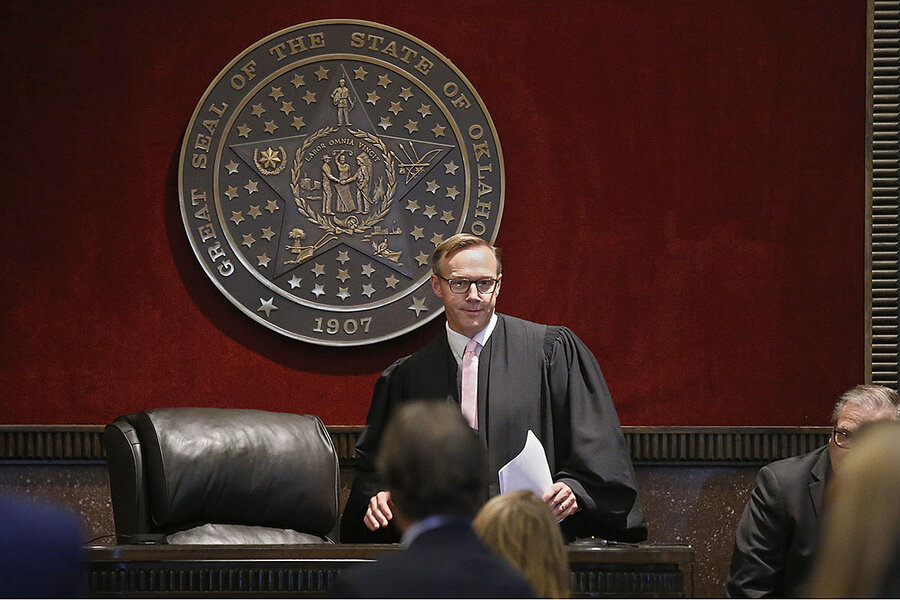

Judge Thad Balkman ruled that Johnson & Johnson’s “false, misleading, and dangerous marketing campaigns have caused exponentially increasing rates of addiction, overdose deaths and neonatal abstinence syndrome” (NAS) violated Oklahoma’s public nuisance law.

Sales reps for the company were not provided any training “on the disease of addiction ... [or] related to the history of opioid use and epidemics in the U.S. or human history,” the opinion added. Moreover, the defendants sought to convince doctors that patients showing signs of addiction were in fact suffering from undertreatment of pain, and needed more opioids – not less.

Oklahoma Attorney General Mike Hunter, in a phone interview with the Monitor, accuses Johnson & Johnson of waging “a multimillion-dollar brainwashing campaign,” conducted in concert with other drug companies, to convince doctors that opioids were only rarely addictive.

“At the end of the day, one of the most important parts of the judge’s decision was establishing causation and responsibility of Johnson & Johnson for the epidemic in the state,” he says.

Attorney General Hunter says the $572 million award does not reflect “the alpha-to-omega harm” to Oklahoma since the beginning of the epidemic, but rather the costs going forward.

The amount of that award was based on the state’s estimate of the costs of abating the opioid crisis for one year, including treatment costs and rehabilitation programs. The court retained jurisdiction over the abatement proceedings, and appeared to leave the door open to a possible increase in damages.

At Compass Clinic, which provides outpatient care for opioid abuse in Oklahoma City, case manager Rhea Frick welcomes the verdict and thinks drug manufacturers should be held accountable.

“Ultimately I think the drug companies need to push the doctors to educate the patients on the dangers and just exactly how addictive the medications are,” says Ms. Frick in a phone interview, adding that the vast majority of the people they serve – “everyday people” like teachers, ministers, veterans, she says – got addicted after being prescribed pain medication following a surgery or injury. “Nobody is warning them about the dangers of how addictive the medications really are.”

“Public’s first glimpse under the hood”

The trial afforded much more transparency than a settlement negotiation, revealing details that could be used in future lawsuits, said Elizabeth Burch, a professor at the University of Georgia School of Law, in an email. In particular, the public learned about how a subsidiary created a new type of opium poppy that “enabled the growth of oxycodone,” and became the No. 1 supplier not only of that drug but also hydrocodone, codeine, and morphine in the U.S.

“This was the public’s first glimpse under the hood” in the ongoing opioid litigation across the country, she adds.

Balkman’s ruling could be challenged, however. Johnson & Johnson vowed to appeal along with its subsidiary, Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies, and said it had “strong grounds” for doing so, stating that its products constitute less than 1 percent of total opioid prescriptions in Oklahoma, were responsibly marketed, and complied with federal and state laws.

“Janssen did not cause the opioid crisis in Oklahoma, and neither the facts nor the law support this outcome,” said Michael Ullman, executive vice president of Johnson & Johnson, though he expressed “deep sympathy for everyone affected.”

The company also indicated that the judge’s verdict represented a massive overreach of public nuisance law, arguing it ignored a century of precedent.

Judges in North Dakota and Connecticut rejected similar public nuisance claims earlier this year.

That is no guarantee Johnson & Johnson will be successful on appeal, as Oklahoma’s public nuisance law is unusually broad. But there are other potential weaknesses in the ruling.

“The court didn’t really talk about why Johnson & Johnson – which in the opioid marketplace is a relatively small player – is responsible for all these damages, rather than all these other sellers in the marketplace,” says Adam Zimmerman, an associate professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles.

Poster child for an epidemic

Purdue Pharma is a relatively small player, in terms of raw financial resources. Its annual revenues totaled about $3 billion in 2017, compared with more than $81 billion for Johnson & Johnson and $198 billion for pharmaceutical distributor McKesson Corp. last year.

However, Purdue’s OxyContin turned its owners, the Sackler family, into one of America’s richest families, surpassing the Mellons and Rockefellers.

Together, Purdue and the Sackler family have been branded as the central villains of the opioid epidemic. There have been protests outside the company’s Connecticut headquarters, museums have turned down Sackler family donations, and Harvard University has been asked to remove the Sackler name from campus buildings.

Numerous allegations stretching back years claim the company helped spark the opioid crisis in the 1990s through aggressive and deceptive marketing of OxyContin and its addictive potential. Purdue pleaded guilty in 2007 to misbranding the drug and paid $600 million in fines, and in March the company settled a lawsuit brought by the state of Oklahoma for $270 million.

“For years, members of the Sackler family tried to hide their role in creating and profiting off the opioid epidemic,” said Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey Wednesday. “We owe it to families in Massachusetts and across the country to hold Purdue and the Sacklers accountable, ensure that the evidence of what they did is made public, and make them pay for the damage they have caused.”

Purdue and the Sackler family have denied the allegations in more than 2,000 lawsuits against them, but said in a statement that while the company “is prepared to defend itself vigorously in the opioid litigation,” it believes “a constructive global resolution is the best path forward.”

According to news reports, they are offering to declare Chapter 11 bankruptcy, and then restructure into a for-profit trust aimed at easing the opioid crisis. The trust would provide cities, counties, and states in the settlement with drugs for preventing overdoses valued as well as the profits from Purdue’s sales, together valued at $7 to $8 billion. The Sacklers would add $3 billion from their estimated net worth of $13 billion.

“The people and communities affected by the opioid crisis need help now,” Purdue’s statement added.

The company’s settlement with Oklahoma earlier this year hinted at its willingness to take long-term responsibility for abating the opioid epidemic, with the $270 million agreement including $75 million to be put toward an addiction treatment and research center. That may still not be enough for the plaintiffs suing Purdue, however.

“They’ve sort of been the poster child for all of this,” says Professor Ausness.

“In terms of their culpability, it probably isn’t [fair] considering the total cost of the opioid epidemic and their contribution to it,” he adds. “On the other hand, what they may be saying is, in effect, ‘This is all we’ve got,’ and if that’s true then that’s all [plaintiffs] are going to get no matter how culpable Purdue is.”

“What is the price?”

The federal government will have its own responsibilities moving forward, says Professor Ausness, particularly now that the opioid epidemic is being driven more by illegal drugs like heroin and fentanyl than prescription painkillers.

And despite the two developments this week, the major questions over who is responsible for the opioid epidemic remain.

“The big problem is a lot of harm is already done,” says Professor Zimmerman. “How do we remediate that problem? What is the price of dealing with that problem? And to what extent are defendants in these cases responsible for this problem?”

In a sense, he says, this is a crisis that “we’re all kind of responsible for,” and it will take broad cooperation to formulate a comprehensive solution.

“This is one step, a small step, toward trying to fix it. But it’s not the only step, it can’t be,” he says. “Litigation will provide one well-needed source of funds to combat the crisis. But hopefully it also sparks a dialogue in our communities and state legislatures and Congress to think about more systemic solutions.”