Fenway Park: Living link to baseball's past turns 100

Loading...

Fenway Park isn't just the storied home of the Boston Red Sox. It's also a venue, perhaps more than any other ballpark now in use, that links the nation to baseball's history.

Sure, the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y., serves as a kind of pantheon of the sport's legend and lore.

But Fenway Park – which celebrates its first 100 years Friday – is the sport's living shrine.

It's not that Fenway can claim to be what Wimbledon is to tennis – the perennial home of epic events in the sport. But as the oldest major-league ball field still in use, it offers the nearest connection that today's fans can find to an earlier era when every game was played in daylight, when the telegraph defined high-tech communication, and when starting pitchers routinely pitched a full nine innings.

And it's not just that the park is old. It's also distinctive, known most of all for that giant "Green Monster" wall that dwarfs those who play left field. It's also home to a team that has captured an outsize share of affection in the hearts of fans beyond Boston.

The Sox have a story woven with themes that resonate widely for the sport's fans: hope (think Carlton Fisk's 12th-inning home run in the 1975 World Series), heartbreak (recall all those decades of championship drought) and flamboyant characters (Babe Ruth, Luis Tiant, and Jonathan Papelbon, to name a few).

So, even though most other historic ballparks were torn down long ago, Fenway has survived.

It's survived because the park is beloved by Boston's passionate fans and because the current team owners had a vision for making improvements that have allowed the park to keep functioning, flaws and all.

The celebrations Friday coincide with a game between the Sox and the New York Yankees, longtime archrivals in the American League's eastern division.

It was the sale of Sox star Ruth to the Yankees, in 1920, that prompted the long-running talk of a "curse" on Boston. The Yanks began their chain of World Series wins under Ruth, and the stadium where they played for decades was deservedly known as the "House That Ruth Built."

But that "house" in New York City is now gone. Fenway Park lives on.

The other classic major-league ballpark still in use is Wrigley Field, home of the Chicago Cubs, which opened in 1914. Wrigley can tell its own tales of hope, loss, and devoted fans. But those stories don't tend to have the intensity that Boston has provided over the years with its down-to-the-wire pennant races and recent World Series wins.

So, in a tribute to Fenway's 100th anniversary, here are some highlights of the Sox and their ballpark:

• Fenway Park's first game actually came on April 9, 1912, but it was an exhibition between the Red Sox and Harvard College. Eleven days later came the major-league opener against the New York Highlanders (now known as, yes, the Yankees). In a foretaste of thrills to come, the Sox won that game 7-6 in 11 innings.

• John F. Kennedy's grandfather, Boston Mayor John Fitzgerald, threw the ceremonial first pitch on April 20, 1912.

• In 1912, the Sox won 105 regular season games, the American League pennant, and the World Series. The team's other World Series titles while residing at Fenway came in 1915, 1916, 1918, 2004, and 2007.

• Along with the Green Monster wall, notable features of the park include "the triangle" (an angular oddity in center field where balls can ricochet) and foul poles named after Sox greats Johnny Pesky (the right-field pole) and Fisk (the left-field pole).

• Despite the long drought in World Series wins, the Sox story between 1918 and 2004 was far from dull. It included trips to the World Series in 1946, 1967, 1975, and 1986. The championship aspirations were spoiled by the St. Louis Cardinals (with a "mad dash" by Enos Slaughter coming home from first base), the Cardinals again (led by the overpowering arm of Bob Gibson), the Cincinnati Reds' "Big Red Machine," and the New York Mets (after a ground ball infamously slipped past Sox first baseman Bill Buckner to force a Game 7). Some of those moments occurred outside Fenway Park, but others, like Fisk's home run, are forever etched in the memories of Boston fans.

• In October 1978, Bucky Dent shocked Boston by hitting a home run over the Green Monster, allowing the Yankees to edge out the Sox in a crucial division playoff game at the end of the season.

• A turnabout moment came in 2004, when the Sox and Yanks faced each other in the American League Championship Series. The Sox appeared poised to lose in four straight games, when Kevin Millar drew a bottom-of-the-ninth walk, pinch runner Dave Roberts stole second base, and Bill Mueller drove him home with a single. The Sox went on to win the ALCS and then took their first World Series in 86 years.

• As befits its place in the sport's lore, Fenway served as a mecca for Kevin Costner and James Earl Jones in the baseball film "Field of Dreams."

• The park very nearly didn't survive. For years, team owners and local politicians grappled with questions about the field's future. Boston Globe sportswriter Bob Ryan, commenting on TV before the celebration, said the team might easily be playing now in a "theme park" field modeled on Fenway, but thanks to a few fateful decisions, "we have the real thing."

• As old as Fenway is, not all Boston's great baseball moments came with that as the home field. Pitcher Cy Young threw the first pitch at Huntington Avenue Baseball Grounds in the modern World Series in 1903 while leading the Boston Americans to a championship. The Americans became the Red Sox in 1908.

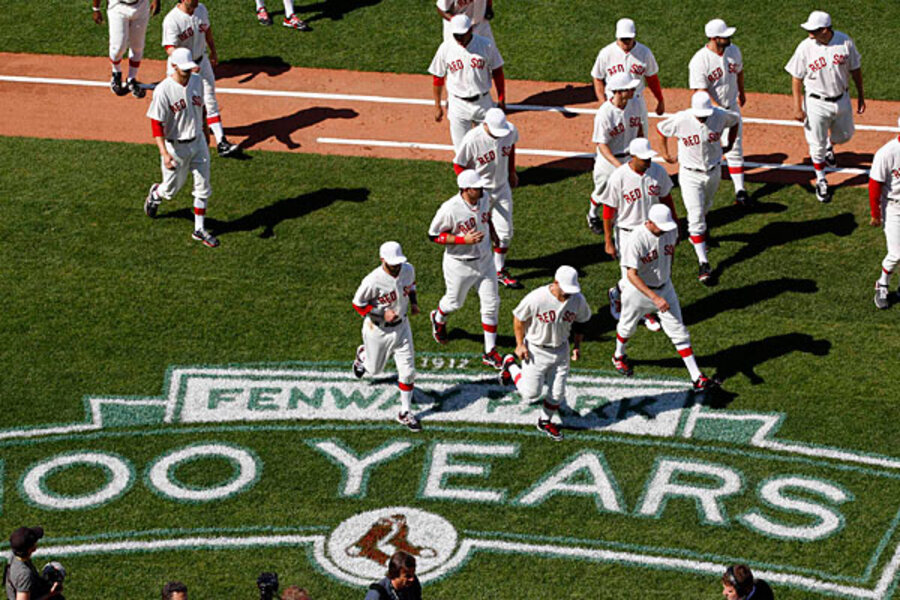

The celebration Tuesday brought a legion of former Sox players onto the field before cheering Boston fans. Among them were Jim Rice, Dwight Evans, Jim Lonborg, Pedro Martinez, Nomar Garciaparra, Dennis Eckersley, Buckner, Tiant, and Fisk. And the man who led the team back to national prominence starting in the 1960s: Carl Yastrzemski.

Then, with the former greats congregating on the field, composer John Williams unleashed a "Fanfare for Fenway."

Where once Bostonians talked of a "curse," on this day it may feel more accurate to borrow a line from Shakespeare and call Fenway a "blessed plot" of turf, brick, and bleachers that could thrive for years to come.